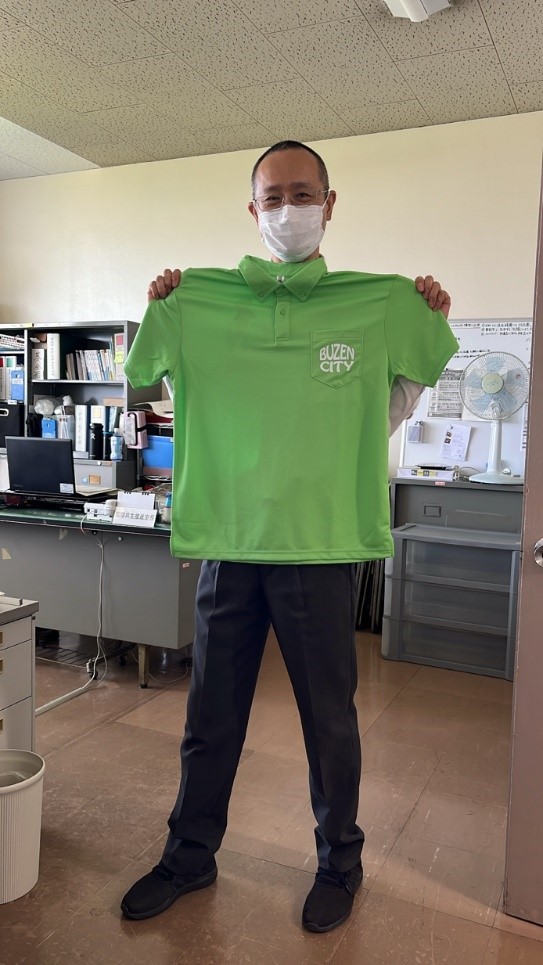

by Sarah Bijlsma

A question that inevitably comes up when thinking about (urban migration to) rural Japan is where ‘the rural’ as a unit of analysis begins and ends. To put it differently, is rural Japan defined by population density, municipal borders, the conceptual boundaries of ‘the countryside,’ linguistic terms like chiiki (region), inaka (countryside), or chihō (district), or by a combination of all? In my research on Miyakojima it is the term shima (island) or ritō (remote island) that is used by people to reflect on the space they inhabit. Being a piece of land fully surrounded by water, I often feel that the term is applied to describe an isolated and more or less homogeneous space [1]. Yet, spending time on Miyako I realized that its 159 km² is used, planned, and negotiated by different people in fundamentally different ways.

To begin with, Miyako has a small urbanized area on the west side of the island. This is where most of the 52,814 inhabitants live [2]. However, when I strolled through the narrow streets, I was especially struck by the many multi-story buildings with a different karaoke bar or hostess club on each floor. One night I spoke to a girl named Mika who works in such a hostess club. She told me that she was originally from Osaka and had moved to Miyako three months earlier. On Miyako, only migrants like herself work as hostesses as the job comes with a number of benefits for them. For example, the club provides a dorm to live in, food and free drinks, a relatively high salary, and even pays for a one-way airplane ticket from the girl’s home city to Miyako. Mika had been a hostess for many years but stated that she likes the work way better on the island. In Osaka, her customers were mainly middle-aged salarymen. In contrast, on Miyako her customers are tourists and Japanese construction workers who are more or less the same age. So she gets paid to party, get drunk, and talk to people she would also be friends with outside of her job.

Club Venus and other hostess clubs in the center of Miyako

Copyright © Sarah Bijlsma 2022

The seaside is an area that is marked by the concrete of hotels and resorts. These buildings did not exist until a few years before; the year 2015 marked the beginning of a large-scale construction rush that became known as the ‘Miyako Bubble’. I have been told that the local population hardly benefits from these hotels, as they are built, managed, invested in, and used by people from Japan. Mika’s boyfriend is someone who knows Miyako’s beach areas very well. Originally from Yamanashi-ken, he worked at a real estate company in Tokyo before moving to Miyako in 2021. He started his own SUP business next to Yonaha-Maehama Beach, Miyako’s number one tourist spot. When I asked him if there are any locals who make use of his services, he said that locals do not spend time at the beach at all. For them, the ocean is something ordinary (atarimae). The only locals you see are the owners of jet ski companies, many of whom are yakuza. He does not know the exact reason for this, but since a lot of money goes is turned over in these businesses and customers pay in cash, they seem to be the perfect vehicles for laundering money.

Miyako is known by Japanese tourists for its bright blue sea

Copyright © Sarah Bijlsma 2022

While Miyako’s city center and beaches are the terrains of Japanese tourists and emigrants, the inland belongs to the local population. Miyako has no mountains and these inner landscapes are characterized by wide sugarcane fields. In a small village on the east side of the island stands the house of Hiroto and his wife. The couple, originally from Miyako, run a small restaurant while raising their eight children. When they were still a family of six, they traveled around Japan to learn about alternative ways of agriculture, architecture, and education. When they returned, they could not find a house and decided to build a hut from old cans and clay in a banana field. Their fifth child was born there. After six months, they bought an old house which they fully rebuilt. The roof was taken off to make the house twice as high. A second floor was built, accessible only by log, and it contains so many books that they call it their ‘library.’ There are no separate rooms in the house; everyone can just grab a futon and sleep wherever they want. The walls of the bathroom are made out of corals, and the toilet is largely built of glass bottles that cast a pleasant green light into the house whenever in use.

The house of Hiroto and his wife

Copyright © Sarah Bijlsma 2022

These three examples illustrate that, far from being a homogeneous environment, the geography of Miyako is organized according to different social groups. As such, the landscape of Miyako can be ‘read’ as text [3]: Taking a close look at the island’s architectural structures provides insights into the fabric and social relationships that are being negotiated on this small piece of land.

Endnotes

[1] Gillis, John R. 2007. “Island Sojourns”. Geographical Review, Vol. 97, No. 2, pp. 274-287.

[2] As of June 2022. Miyako Mainichi. 27.06.2022. Miyako keniki jinkō 35nen buri souka / 20nen kokuseichōsa sokuhō [Miyako’s population increases for the first time in 35 years / 20 year preliminary census report]. Via https://www.miyakomainichi.com/news/post-142738/ (accessed on 19.10.2022)

[3] Cosgrove, Denis. 1989. “Geography is everywhere: culture and symbolism in human landscapes.” In: Derek Gregory & Rex Walford (eds.), Horizons in Human Geography. Barnes & Noble. pp. 118–135.