Student post: In our blog series we occasionally present exceptional work of our students on China’s urban-rural integration to a wider audience. This is a post by Daniel Kroth, student at Michigan State University currently on a year abroad at Albert-Ludwigs Universität Freiburg supported by the DAAD. The post started as a paper for the MA course “The Next Great Transformation”. The opinions expressed in this blog post belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the research project.

by Daniel Kroth

Through “quirky but revealing” juxtapositions, University of California Irvine professor Jeffry Wasserstrom demonstrates the value of using inexact comparison to interrogate long held assumptions about China and Chinese history. These openly imperfect juxtapositions cultivate “fresh thinking,” and bear as much utility in their well-discussed insufficiencies as in their perceptive analogies. In this post, I will apply this analytical lens to the discourse surrounding a fascinating challenge facing Chinese policymakers in their efforts of “rural revitalization”: bicultural education in Tibet.

The difficulties of effectively educating a culturally and linguistically distinct population through the seismic changes of urbanization and modernization are formidable. They may not be, however, unique to China. Many other states have tackled this challenge with a range of policies to varying degrees of success. The United States, with its nearly six million American Indians speaking 170 distinct languages, may provide an interesting foil to Chinese bicultural education policies. Though some Tibetans and American Indians themselves identify their cultural and historical similarity, outside comparisons between Tibetans and American Indians often end in acrimonious and unproductive discussions of American and Chinese imperial legacies.A more targeted comparison of specific policies and structural realities affecting these culturally and linguistically distinct, synthetically urbanized (or urbanizing) populations may provide fertile ground for Wasserstrom’s approach. Here, I write a “ninth juxtaposition” using this method as an analytical inroad to education in an urbanizing Tibet.

In educating these populations, American and Chinese policymakers face two similar obstacles: 1) The logistical and infrastructural challenges of providing education in typically less developed areas, and 2) The political challenges of preserving cultural identity while providing a basis for modernization and prosperity in the context of a globalizing economy.

The Badlands on Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota, USA. Low population density and extreme weather in the American Great Plains and on the Tibetan Plateau can complicate education efforts and transportation schemes. Photo by D. Luchsinger of the National Parks Service

Spaces for Education

Low population density, limited transportation infrastructure, and a lack of suitable educational facilities pose significant challenges to both American Indian and Tibetan students, and to the American and Chinese policymakers serving them.

American Indian and Tibetan students often find themselves in undesirable facilities for different reasons. China has been aggressively building new schools in Tibet since 1999. Though the economic realities of constructing schools to serve low population density areas resulted in substandard facilities early on in some locations, Tibetan school facilities today are generally well funded and well maintained. These schools are, however, often devoid of the cultural symbolism found in Tibetan-run schools. In Tibet it seems, complaints regarding facilities stem more from this cultural sterility than from infrastructural quality. In the United States, particularly in the Great Plains, insufficient funding and maintenance has resulted in run-down schools with outdated classroom technology in many cases. Many American Indian schools still have dial up internet, for example. In either case, students face an uphill battle when competing with their national-majority peers. Subpar facilities can negatively impact both student and teacher performance. Perhaps more importantly though, the disparity between rundown or inferior Bureau of Indian Education schools and other “majority” schools in the U.S and a lack of Tibetan cultural presence in Tibetan schools can reinforce a perception that these culturally distinct students are not equally valued. This can create tension between local communities and the central/federal governments operating their schools. This disparity can also undercut students’, parents’ and teachers’ sense of agency, ownership, and pride in their educational process, limiting participation and cooperation.

The condition of schools and the issue of school transportation are closely related. Budgetary issues that lead to subpar facilities often affect transportation similarly, and transportation difficulties are further stressed by students traveling farther to avoid these insufficient facilities. In the American Great Plains, many Native students travel great distances to avoid critically outdated or underfunded schools. Some American Indian students, for example, drive upwards of 300 miles (482 kilometers) per day to attend more suitable schools. In Tibet, altitude, remoteness, school consolidation projects and limited transportation infrastructure exacerbate the difficulty of travel and create a perception of danger. This perception, not entirely without substance, is expressed in a case study of locally operated schools by one mother of four children she declined to send to a locally run rural school in Kurti Ribo:

“I was very worried that my children might get attacked by stray dogs and wolves on their way to school. I was also very worried they might drown in the big rivers nearby.”

In both cases, travel to schools is more than a question of convenience. Long commutes to suitable schools, sometimes as a result of school consolidation policies, can impose undue burdens on students and parents who provide their own transportation, incur operational costs in programs where transportation is provided, and undercut a sense of regional identity and agency over schooling. All of these negatively impact student performance. Urbanization and the facilitation of locally operated schools could ameliorate these difficulties.

As noted above, this comparison is not a perfect one. American Indian and Tibetan communities find different issues with their school facilities or commutes to them, and the American and Chinese national governments have pursued different strategies to improve the spaces for education and travel to them. Despite this, both situations have been insufficiently ameliorated or even directly exacerbated by government policy or execution of policy.

The United States funds all public schooling at the state level through property taxes – except for American Indian schools, which are funded federally and typically operated by the Bureau of Indian Education, or BIE. Attempts to address facilities and transportation issues often come in the form of increasing funding to schools themselves to remodel facilities, and purchase and operate busses. This policy is widely viewed as ineffective, and partly as a result, 93% of American Indian students travel to attend state public or charter schools not run by the BIE. American Indian education leaders often criticize the BIE for its inexperience in operating schools, and for being out of touch with student needs. Policy changes on this front come slowly, but increasingly trend towards turning school operations over to Native entities with federal funding.

In Tibet, an increasing reliance on development projects and a state-led development drive lead to a rapid (and perhaps artificial) concentration of the population. While this may provide better access to social services, it often appears to be at the cost of losing traditional ways of life. The project-based economy often involves the undertaking of projects for the sake of personal career advancement or to take advantage of temporarily available funding.

This frequently incentivizes the adoption of policies which do not align with the needs of students. For example, school consolidation (chedian bingxiao), aims to focus resources by closing some rural facilities. The aforementioned school in Kurti Ribo was slated for closure and consolidation as part of a school consolidation project. Though the project would have been beneficial for local officials, the considerably longer (ten kilometer) walks to school and a loss of local agency over schooling this project would have entailed sparked local resistance. In an unusual result, this ultimately prevented the consolidation.

The Challenges of Bicultural Education

In addition to these logistical and infrastructural difficulties, policymakers, educators, and students face societal challenges inherent to bicultural education. Many of these challenges result from a perception of diametric opposition of cultural heritage and workplace readiness. Of particular concern are the issues of language preservation, culture in the curriculum, and agency over schooling, all of which can significantly impact educational outcomes.

Any discussion of the use of Tibetan or American Indian Languages in the classroom must recognize significant differences between them. Tibetan has a much broader speakership, and is still in use as a cultural lingua franca for a large, contiguous region. American Indian languages, of which there are many, are spoken by smaller communities and are often used in a more limited role. In both cases however, the student populations in question feel a cultural attachment to non-majority languages. This poses two key challenges. First, and in both cases, availability of teachers and educational materials in these languages can be limited. Second, there exist, particularly in China, questions about their economic usefulness to students given the prevalence of English and Mandarin on a global scale.

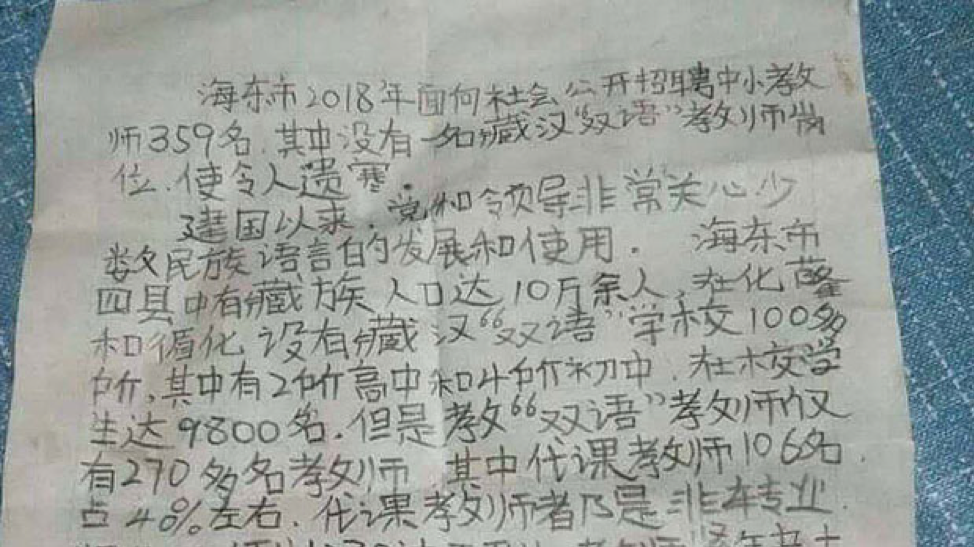

A letter sent in 2018 by Tibetan students in Qinghai asks that more bilingual teachers be hired.

This concern about economic competitiveness is sometimes posed against the value of language as a facet of culture. Frequently, courses for younger Tibetan students are taught in Tibetan, while STEM courses in secondary education are often taught in Mandarin. Many Tibetans are not native speakers of Mandarin. This can create additional difficulty, in that the use of Tibetan serves both a cultural and practical function. As schools have pivoted towards greater ratios of Mandarin language instruction, students and parents have expressed concern for their cultural autonomy. Both groups have identified increased local involvement in education as a desirable method for simultaneously maintaining cultural autonomy and preparing students for success in broader society. As Anhiwake Rose, Executive Director of the National Indian Education Association notes in a related opinion, this involvement not only necessitates local individuals as educators, but also local culture in the curriculum.

“Unless educators make sure Native cultures are included in school culture, and Native history is taught in the classroom, Native students won’t do as well as they could either academically or socially.”

This desire for involvement, representation, and agency, and the perception of the school as a projection of state or ethnic majority power also colors both situations. U.S. American Indian education policy before 1938 involved forced assimilation and the deliberate destruction of Native culture in boarding schools. The “Kill the Indian, save the man” mantra of “modernizing” people themselves, rather than systems, left an indelible mark on American Indian’s views of state run education. In many cases, the failure of education to deliver on the promise of social mobility has further undermined the perceived value of federal educational systems. These cultural memories undergird a distrust of federal educational schemes, and contributes to the perception of the school as a cultural proxy for the state.

In Tibet, similar questions about the cultural and political role of the school have arisen. State-led education efforts often include the goal of “modernizing” the Tibetans themselves, though emphasis on Mandarin language ability, limiting religious expression, and overt as well as indirect insistence on changes in traditional ways of life. The state and the Tibetans often view such efforts differently, with the state insisting that such changes prepare Tibetans to succeed in a modern world, and with Tibetans viewing them as a threat to their cultural autonomy. Though American Indian wariness is largely due to past abuses and Tibetan wariness is largely due to a fear of state-facilitated cultural change, both groups have expressed a similar concern for cultural and linguistic autonomy, and have insisted that students are better served when Tibetans or American Indians have a hand in educational processes.

A comparison on logistical and cultural fronts highlights the similar demands of students and their advocates, and showcases differing reactions to these demands. A more thorough exploration of such a juxtaposition could provide a better understanding of both situations, and could provide additional context for Tibet’s rural transformation. ·

Questions may be directed to krothdan@msu.edu.