by Cecilia Luzi

When I started my PhD, the original plan was to leave for fieldwork in Japan around June 2021. Since entering Japan was still not possible at the time due to the Covid-19 pandemic, the whole group decided to postpone fieldwork. We were excited about the announcement of the reopening of Japan’s borders in the beginning of November 2021, just like many other researchers who study Japan. We prepared all the paperwork, but due to the emergence of the new Omicron variant, the government decided to extend the entry ban. This decision left us disappointed and discouraged, as we will need to drastically change our research plan.

Copyright © Cecilia Luzi 2021

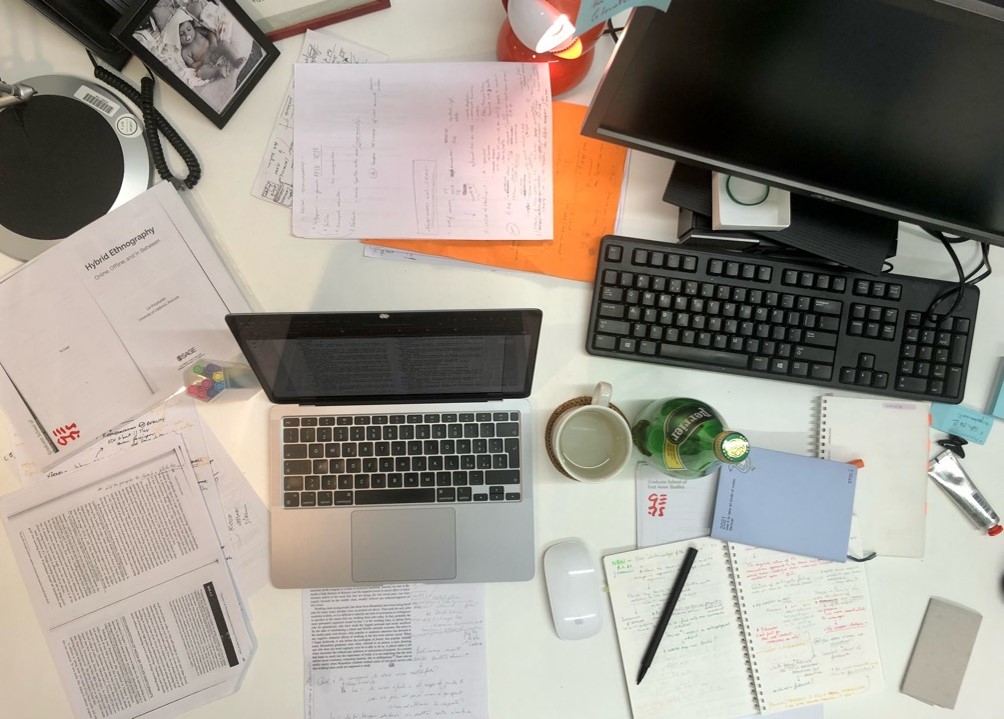

In this context, I started a “digital ethnography” of social media profiles and websites of people living in northern Kyūshū in order to move on with my research. It took me some time before adapting my gaze to this new territory, and still today, when I scroll down in-migrants’ Instagram profiles and YouTube pages, I sometimes hear a voice on the back of my head telling me that I should get back to work. As Góralska (2020, 46) put it: “It is my fieldwork, but an unaware observer would probably assume that I am just wasting my time before bed”. Maybe this is the reason why it is so hard to fully commit to this kind of ethnography. Working in the digital world and using it as a field of research requires a set of tools and principles that are codified, selected and debated, as well as a training for the ethnographic eye, which needs to learn anew how to single out important information from the abundance on the internet.

However, after the initial irritation of not being in the physical field discovering bizarre shops, ordering delicious meals at restaurants or sipping a fresh roasted black coffee in a café, I learned how to domesticate the digital space and gather useful data from it. For instance, I discovered a strong network of temporary markets and fairs attended by in-migrants both as vendors and as costumers. They are held all year long and are distributed within the four prefectures of northern Kyushu, which makes them a fascinating field to explore the social structure of in-migrants’ communities. I also learned that the rhetoric of renovation and re-use of abandoned spaces such as empty houses, studios, warehouses, schools and post offices, is pervasive in the experience of in-migration. Thanks to Instagram, I now have some contacts that can potentially become gatekeepers once I will arrive in Japan.

Copyright © Cecilia Luzi 2019

I enjoyed reading blog interviews, looking at pictures and watching interesting videos, but in the end, I cannot help feeling a bit nostalgic and frustrated. I wonder if what we call now “digital fieldwork” (Góralska 2020), “virtual fieldwork” (Robinson and Schulz 2009) or “online fieldwork” (Howlett 2021) can really be considered fieldwork in the original anthropological sense of the term. Fieldwork is the “intimate participation in a community and observation of modes of behavior and the organization of social life” (Keesing and Strathern 1998, 7), and has been characterized by the extended presence of anthropologists within the community they study, whether next-door (e.g. Fassin 2011) or in another continent (e.g. Tsing 2004). The aim of fieldwork is at the same time “to understand the inside view of the native peoples and to achieve the holistic view of a social scientist” (Powdermaker 1969, 418). Yet, how can we have powerful insights about the people we study if we cannot immerse in a community and try “learning as far as possible to speak, think, see, feel and act as member of its culture and, at the same time, as a trained anthropologist from a different culture” (Powdermaker 1966, 9)?

Copyright © Cecilia Luzi 2019

Analyzing travel and food blogs, studying social media profile and examining prefectural and municipal websites has been a crucial work for my thesis development in the last months, and prepared me for my future fieldwork. I was able to discover places and come up with new questions that I probably would have missed if the pandemic did not force me to work with my computer for a much longer period than planned. However, I have the feeling, now more than before, that this is just preparing me for the actual fieldwork, as Anthropology requires the prolonged sharing of space and time with the people met in the field. For my project, this means that I will have to organize a different ethnography than the one I had in mind. Originally, I wanted to conduct interviews at a later stage, but I will now try to schedule online interviews from Berlin during the upcoming weeks. At the same time, I am still working as if I was preparing for my fieldwork, because I am not giving up on the idea of being in Japan soon to do my ethnography as fieldwork is the “central activity of anthropology” (Howell 1990, 4) and the “source of anthropology’s strength” (Keesing and Strathern 1998, 7). “Digital ethnography” lacks this as “there is more to fieldwork than just the fact that it is a scientific method of gathering data” (Sluka and Robben2007, 14). In my opinion, online fieldwork is lacking the intimate full-immersion that characterizes the ethnographic craft. So, I keep my finger crossed that those digital profiles will become actual persons I can spend time with.

References

Fassin, Didier. 2011. La force de l’ordre: Une anthropologie de la police des quartiers. Paris: Seuil. (Translated by Rachel Gomme as En-forcing Order: An Ethnography of Urban Policing. Cambridge:Polity Press, 2013.)

Góralska, Magdalena. “Anthropology from home: Advice on digital ethnography for the pandemic times.” Anthropology in Action 27.1 (2020): 46-52.

Howell, Nancy. 1990. Surviving fieldwork: A report of the advisory panel on health and safety in fieldwork, American Anthropological Association. No. 26. Amer Anthropological Assn.

Howlett, Marnie. “Looking at the ‘field’ through a Zoom lens: Methodological reflections on conducting online research during a global pandemic.” Qualitative Research (2021): 1468794120985691.

Keesing, Roger M., and Andrew J. Strathern. “Fieldwork.” Cultural Anthropology: A Contemporary Perspective (1998): 7-10.

Powdermaker, Hortense. 1966. Stranger and Friend: The Way of an Anthropologist. New York: Norton.

————1969 “Field Work”, In: The International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences. D. Sills, ed., pp. 418-24.

Robinson, Laura, and Jeremy Schulz. 2009. “New avenues for sociological inquiry: Evolving forms of ethnographic practice.” Sociology 43.4, 685-698.

Sluka, Jeffrey A., and A. C. G. M. Robben. 2007. “Fieldwork in cultural anthropology: An introduction.” Ethnographic fieldwork: An anthropological reader 2, 1-48.

Tsing, Anna. 2004. Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.