by Maritchu Durand

This year in early May, I took a few days off to visit my family in the south-western French countryside and to enjoy the mild and sunny spring. The region’s nickname “the French Toscana” suits the hilly region with small fields of cereal grain or sunflowers well. A few kettle farms spread over the country and small quiet villages with old stone farmhouses, vegetable gardens and the obligatory area for playing pétanque [1] on the village square right next to the small church and a one-room city hall can be found here and there.

Traditionally an agrarian region, most of the farmers are now either close to retirement or do other jobs on the side. They are usually part of a cooperative that sell their crops to bigger firms. However, amid this rather industrial production chain, there are exceptions that started in the 1968’s back-to-the-land movement that seek alternative and more direct ways to connect farmers and consumers.

Copyright © Maritchu Durand 2022

One such example is the “Poppy Cabin”, a 30 minutes walk from my grandparents’ village. You can enter the bright red cabin from the small countryside road. Although it is in the courtyard of the farmer who manages it, I never meet anyone. Depending on the season, there are different products for sale, all either certified organic or from the so-called “reasoned agriculture” [2]. The farmer sells mostly cereals and pulses in various forms that he produces: dried lentils and chick peas, rye, spelt, wheat or chick pea flour are almost always available. You can also find honey, sunflower oil, onions, garlic or different root vegetables and a local artisan’s hand-made soap.

Copyright © Maritchu Durand 2022

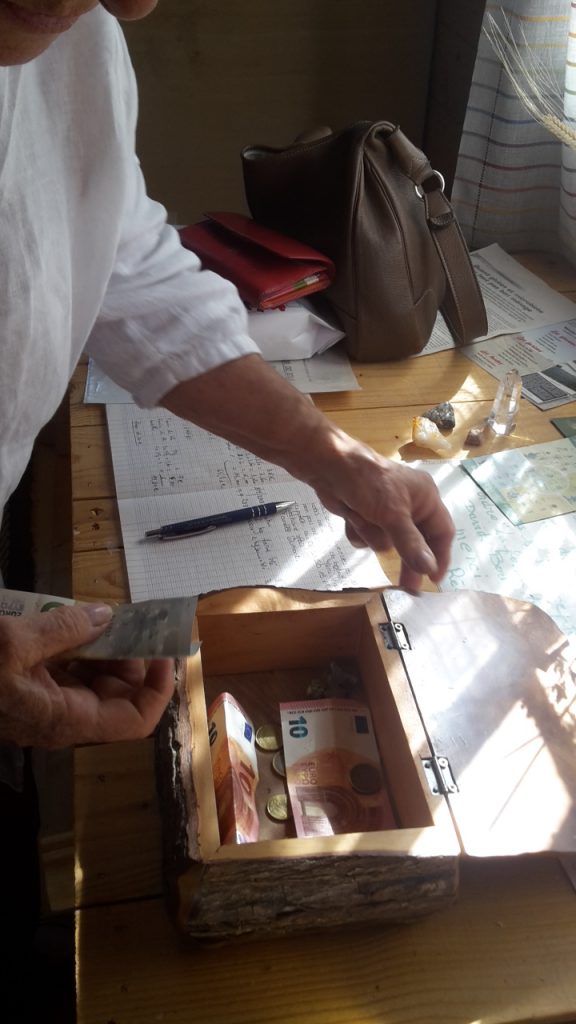

Once you have filled your basked, you simply write down your name a well as what you bought and how much you paid on the ledger and put the money in the small wooden box on the table. It is a system based on trust and a strong network: there are no signs on the cabin, it merely works by word of mouth. At the same time, by writing down your name, you lose the anonymity usually linked to consumption.

While browsing through the home-made packages of flour, I was strongly reminded of a very similar system in Japan: the mujin hanbai stalls – mujin stands for “without anyone”, and hanbai for “sale”. When I travelled through the Japanese countryside, I frequently encountered small stalls on the side of the road. Usually very rustic and simple shelves that are filled with produce packaged by locals: mikan, umeboshi, daikon and many other local and seasonal products for an astonishingly cheap price. I was very surprised when I first saw an umeboshi stall. It was so cheap that I thought I was mistaken, I therefore hesitated, afraid of paying the wrong price, and I passed by without buying anything. I regret it until this day.

Copyright © Maritchu Durand 2017

Although different in its interpretation, the core of both systems is the same in Japan and in France. It is a system based on trust within a small community. First, the seller trusts the consumer to pay the right price, take only what he or she paid for and leave the place unharmed. In return, the customer trusts the producer with the quality and safety of the product. Since it is locally grown in a place the customer sees and values, he or she might find a meaning in buying the produce beyond the mere fact of consuming. This is at least what my grandmother told me when she first brought me to the Poppy Cabin: she wanted to support the local farmer, a young passionate return migrant who had taken up his grandfather’s farm. She praised the quality and unique taste of the products she regularly bought and appreciated the ‘no-fuss’ aspect of the system.

Copyright © Maritchu Durand 2018

The Poppy Cabin and the mujin hanbai stalls share the principles of mutual trust, attachment to a community, appreciation of the soil and its produce and connecting producers and consumers. All are aspects that are often associated with an ideal countryside. In the interviews and articles by urban-rural migrants I encountered while working on this project, they mention these aspects very often as the very reasons for moving to the countryside. Although the Poppy Cabin and the mujin hanbai stalls are only small and rare realizations of those principles, they might prove that the ideal images prospective migrants express about the countryside might be more than mere imagination.

[1] Pétanque or boules is a popular game in France where players through heavy metal balls towards a smaller wooden target ball. It is played on village squares and enjoys great popularity in southern France.

[2] The French Ministry of Agriculture defines reasoned agriculture (l’agriculture raisonnée) as a type of farm management that aims at reinforcing the positive impacts of agricultural practices on the environment and at reducing their negative effects. Closely linked to organic farming, it does not however require any certification.