by Shilla Lee

Recent studies on regional revitalization movements in Japan have explored various local initiatives to mobilize the urban population to rural areas (Klien 2020; Manzenreiter et al. 2020). While they provide us with rich contexts, the discussions seem to revolve around an essentially anthropocentric account of regional sustainability. I want to bring attention to my rough ideas about a new perspective to scrutinize the social implication of regional revitalization movements in Japan: to broaden our discussions beyond the human-human domain by exploring problems of depopulation within the wider panorama of human-wild animal (pestilence) relations.

There have been growing cases of wildlife damage in depopulating regions across the globe. Let me briefly mention an article published by The Guardian in January 2021 (Flyn 2021). It talks about how declining fertility rates have led to serious social problems in wealthy countries like Germany and Japan. However, rather than focusing on issues of birth rate per se, the discussion develops into changing human-animal relations in scarcely populated regions. Highlighting a case of akiya (empty house) in Japan, the article directs our attention to how abandoned farms and gardens are reclaimed by wild animals due to an absence of human existence and how we should be more serious about the contrasting state of shrinking human population and prospering wildlife.

In this context, I suggest that we expand our notion of regional revitalization to non-human beings and question whether regional ‘re’vitalization also implies a power ‘re’distribution between humans and wild animals. When discussing rural social problems such as depopulation, aging, and declining local economy, they are dealt with as issues of human society, precluding social and physical spaces shared (or fought over) with non-human beings. We need to think about whether various strategies that attempt to pull in (attract) the human population such as migrants, tourists, and foreign workers to rural regions also pushes away wild animals that are wandering around once human-dominated habitats. As recent studies on human-wild animal (pestilence) relations show (Enari 2021; Enari and Tsunoda 2017; Tsunoda and Enari 2020), remote village communities lack human forces or community spirits to protect crops from wild animal damage and tensions rising from such conflicts lead to increasing practices of wildlife pestilence to control their population.

Copyright © Cornelia Reiher 2015

The prosperity of wild animals beyond human control “can appear a threatening development that points to the retrenchment of human society rather than a benign revival of nature” (Knight 2003:236). Moreover, at a municipal level, increasing conflicts with wild animals not only create economic damages but also undesirable images of rural livelihood, thereby, affecting key strategies of regional revitalization policies that focus on domestic tourism and urban-rural migration. As Knight points out “the impact of the wildlife pest is not confined to the material damage it causes to individual farmers and foresters but extends to its negative symbolism vis-a-vis the community as a whole” (2003:237). As much as rural areas are relying on incoming tourists and migrants for their economic and social sustainability, any source of negative images poses challenges. In this sense, regional revitalization is not only a matter of increasing the human population but also of adjusting human-wildlife relations.

Copyright © Shilla Lee 2019

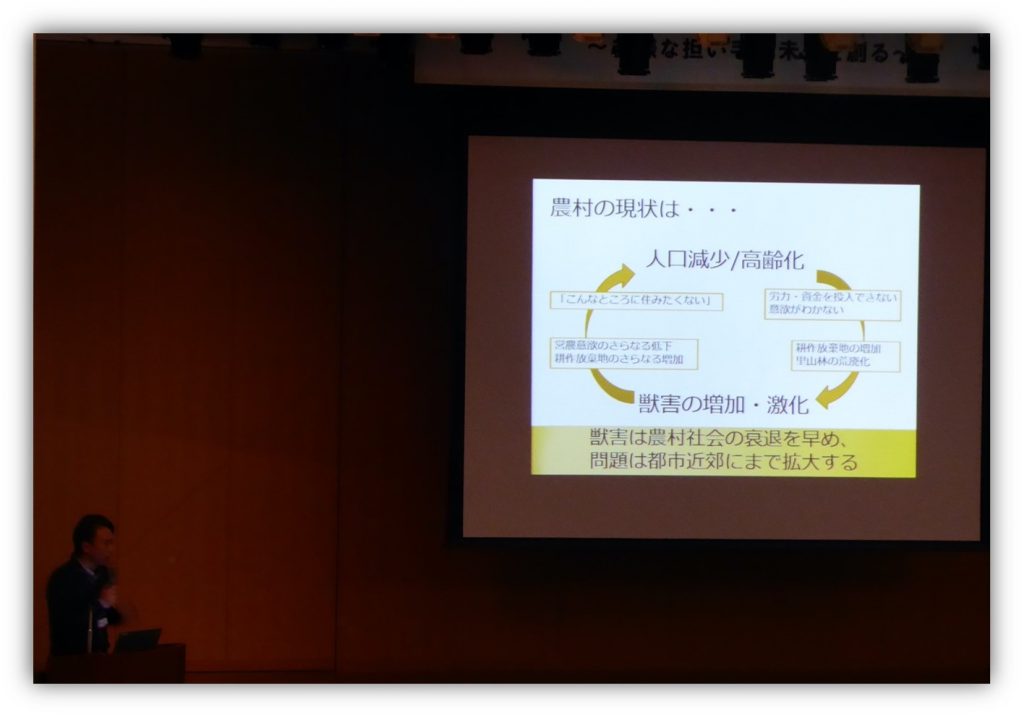

Let me briefly illustrate Wildlife Damage Forum that was held in Tamba Sasayama during my fieldwork in 2018-2019. One of the main actors that dealt with problems concerning wildlife damage in the region was an NPO named Satomon. According to what is written on their official webpage, their key concern is the “wildlife pestilence problem” (jyūgai mondai) by monkeys, deers and wild boars that threatens a Satoyama lifestyle. They argue that wildlife damage takes away the joys of harvesting by referring to young people who move to rural areas and then give up their dreams of living a peaceful country life: “Young migrants who are fascinated by the countryside and relocated to work on farms also said, ‘I cannot work the fields in such a place’ and are giving up their dreams and leaving the villages” (nōson ni miryoku o kanji, ijūshite shinki shūnō shita wakamono mo,” konna tokoro de nōgyō wa dekinai” to yume o akiramete mura o satteiku). It is in this context that Satomon suggests what they call the “wildlife pestilence measure” (jyūgai taisaku) and organizes Wildlife Damage Forum as one of their key initiatives.

An event for the year 2019 was held on a cold day in December in a shimin sentā (citizen center) in Tamba Sasayama. Following an opening speech by the mayor, representatives of various local organizations addressed their ideas to tackle the growing damage by wild animals. A group of social scientists first pitched a behavioral observation of wild boars in the region to examine what kind of damage prevention mechanisms would work. The next speaker demonstrated how the aging community and wild animal damage should be thought of together. Lastly, a group of local middle school students presented a school club activity that produces coin purses from leathers of wild deers. What I found interesting was how they all began with an emphasis on the importance of living with wild animals, however, sought co-existence through curtailing the population growth of the latter. For instance, the business idea presented by the middle school students to rethink human-wild animal conflicts as a way to make profits from the latter was premised on the legitimacy of wildlife hunting and other measures to eradicate the overpopulation of deers. Similar ideas were found in local restaurants that promoted wild boar meats as a local delicacy and a wild meat processing business started by a recent urban-rural migrant. Wild animal damage was being cope by residents by reframing it as a source of economic prosperities and attractive elements of the region.

Copyright © Cornelia Reiher 2015

References

Enari, Hiroto. 2021. “Human-Macaque Conflicts in Shrinking Communities: Recent Achievements and Challenges in Problem Solving in Modern Japan.” Mammal Study 46 (2): 115–30.

Enari, Hiroto, and Hiroshi Tsunoda. 2017. “Emerging Wildlife Issues in an Age of Large-Scale Human Depopulation—Introduction.” Wildlife and Human Society 5 (1): 1–3.

Flyn, Cal. 2021. “As Birth Rates Fall, Animals Prowl in Our Abandoned ‘Ghost Villages.’” The Guardian, January 24, 2021.

Klien, Susanne. 2020. Urban Migrants in Rural Japan: Between Agency and Anomie in a Post-Growth Society. State University of New York Press Albany.

Knight, John. 2003. Waiting for Wolves in Japan: An Anthropological Study of People-Wildlife Relations. Oxford University Press.

Manzenreiter, Wolfram, Ralph Lützeler, and Sebastian Polak-Rottman. 2020. Japan’s New Ruralities: Coping with Decline in the Periphery. Routledge.

Tsunoda, Hiroshi, and Hiroto Enari. 2020. “A Strategy for Wildlife Management in Depopulating Rural Areas of Japan.” Conservation Biology 34 (4): 819–28.

Shilla Lee is a PhD candidate at Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology in Halle, Germany. Her research focuses on the notion of rurality and creativity in regional revitalization practices and the cooperative activities of traditional craftsmen in Japan.