by Simon Hörig

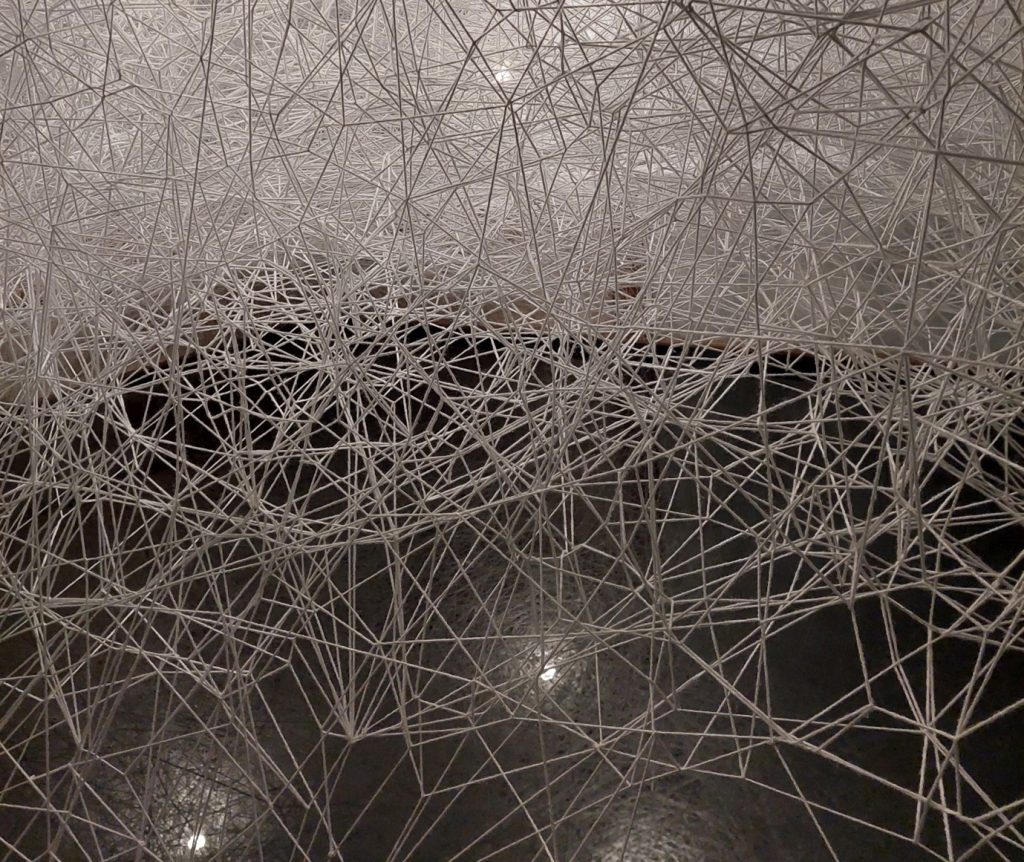

Surrounded by lush greenery, accompanied by the incessant chirping of cicadas in summer and a thick blanket of snow in winter, stands a farm house in Uwayu-mura (Tokamachi-shi) in Niigata Prefecture. The house is from the early Shōwa period with the words ‘Yume no ie’ above the entrance. However, the wood panelling and the impressive roof covering of the house give no clue as to what might be inside. Like many other formerly abandoned houses in the countryside, this akiya kominka was restored and converted into a venue for an art installation as part of the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennial in 2000. ‘Yume no Ie’ or “Dream House” is the art project of artist Marina Abramovic, an interactive art experience where visitors can spend the night in a nightmare created by Abramovic (Ha 2023). In the colour-coded rooms, you can sleep in coffin-like beds while wearing similarly colour-coded sleepwear, eat a Western breakfast and, at the end, document dreams you might have while sleeping in the artwork.

Copyright © Cornelia Reiher 2023

When I looked at the art installation on the internet, I imagined a stay in this strange hotel as a visit to an almost unreal, distorted Japanese house. I noticed an obvious but surprising contrast between the exterior and interior of the kominka. However, I was even more surprised by some of the statements made by the artist Marina Abramovic about her own art installation. In one of her many statements about the Dream House, she said that she wanted this house to be part of the residents’ lives (Ha 2023). I wondered how this could work, as Eimi Tagore (2024) had highlighted the problem of the ‘theme park appeal’ of art installations in rural Japan, which attract crowds of tourists but ultimately cause more problems for local residents than they do positive change (Tagore 2024). Can an art installation really be valued as part of people’s lives in a rural area if, at first glance, the purpose of the installation is only to attract and harbour tourists? How successful is Abramovic’s art project in terms of facilitating the creation of community spaces that she promises?

To answer this question, I wanted to look at Abramovic’s project from multiple angles by consulting literature on art, abandoned houses, the difference between elite based, top-down art projects and a more hybrid case of top-down planned and bottom-up community engaged art projects (Platz 2024, Qu 2020). Statements about the sustainable impact of art work on local residents’ lives can also be found on the Echigo-Tsumari Art Trienniale’s (ETAT) official website.The organizers of ETAT list what revitalization through art projects in the region looks like. For one, it claims that the engagement between artist and local community is an essential part of the art festival and its installations, and it states that the local community becomes a source of collaborators for the artwork. Furthermore, it says that young people from metropolitan areas often volunteer locally, facilitating an intergenerational exchange that results in cooperation and appreciation between old and young (ETAT 2024). This effect of repurposing of vacant houses for art projects on community revitalization and integration is also found in the research of Anemone Platz, in which they show that the so called yosomono, or outsider, can “function as a bridge between the kominka and the residents, the art site, and the visiting audience” (Platz 2024). Through further research into Abramovic’s Dream House, I was able to find this connection between locals and artworks by outsiders. The residents of Uwayu and the managers of the Dream House, Emiko Takahashi, Sachiko Murayama and Masako Takasawa, emphasise that the Dream House has brought about a positive change for the town. They appreciate the reuse of kominka, even if they don’t fully understand the art itself, and say they are excited about the help of young volunteers from the big cities. One of the leaders, Emiko Takahashi, says: ‘When young people who were once volunteers come back with their own children, I feel like my daughter has come back with my grandchild’ (Uchida 2019).

ACHTUNG: Daten nach YouTube werden erst beim Abspielen des Videos übertragen.

ETAT also positions the art projects of its art festivals as unique hubs. They are not just meant to be disconnected works of art, but art installations that connect villages through modern engineering structures and create permanent places within works of art in rural communities (Qu 2020). I would be interested in how the local community is connected to breakfast at the Dream House, for example, as this could be another way of engaging locally. Ultimately, while there is reason to be critical of the content of art projects brought into a rural area from outside (Qu 2020), it is evident that Marina Abramovic’s Dream House integrates the community of Uwayu and exists not just as an artificially implanted artwork, but can be seen as a community-engaged art installation.

References:

ETAT (Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale) (2024), „About ETAT,“ https://www.echigo-tsumari.jp/en/about/

Ha, Thu-Huong (2023), “Sixteen hours in Marina Abramovic’s nightmare hotel,” The Japan Times, July 2, 2023, https://www.japantimes.co.jp/culture/2023/07/03/arts/abramovic-dream-house/

Platz, Anemone (2024), “From social issue to art site and beyond – reassessing rural akiya kominka,” Contemporary Japan 36, 1, pp. 41-56.

Qu, Meng (2020), “Teshima: From Island art to the art island: Art on/for a previously declining Japanese Inland Sea Island,” Shima – The International Journal of Research Into Island Cultures 14, 2, pp. 250-265.

Tagore, Eimi (2024), “Art festivals in Japan: Fueling revitalization, tourism, and self-censorship,” Contemporary Japan 36, 1, pp. 7-19.

Uchida Shinichi (2019), “An over 100-year-old minka (house) repurposed as ‘artwork to stay overnight,’” https://www.echigo-tsumari.jp/en/media/190926-yumenoie/

Simon Hörig is a student in the BA program in Japanese Studies at the Freie Universität Berlin.