by Nakako Hattori-Ishimaru

Ishigaki-shi, Japan’s southernmost city with a population of about 50,000 people, is located on Ishigaki-jima. The semi-tropical Yaeyama islands, the main island of Okinawa, Tokyo and other areas are connected by this transportation hub, which has attracted tourists and migrants. On the location of a former golf grounds, conservative city mayor Nakayama Yoshitaka claimed in 2016 that he had reached an agreement with the Ministry of Defense to build a new camp for the Japan Ground Self-Defense Force (JGSDF). Ever since, Yamazato Setsuko (born in 1937), a native of the island, has been leading the weekly standing protests against the military facility development. For the members’ average age of 74, the group is named the Ishigaki Grannies’ Society to Protect Life and Livelihood (Ishigaki no kurashi to inochi o mamoru obā tachi no kai). As the name suggests, Yamazato san’s actions go beyond just opposing the establishment of a military base. Years of continuous public protests can be time- and energy- consuming, and even sour relations within small communities. But why does Yamazato san feel the need to engage in peace activism so strongly?

Copyright© Nakako Hattori-Ishimaru 2023

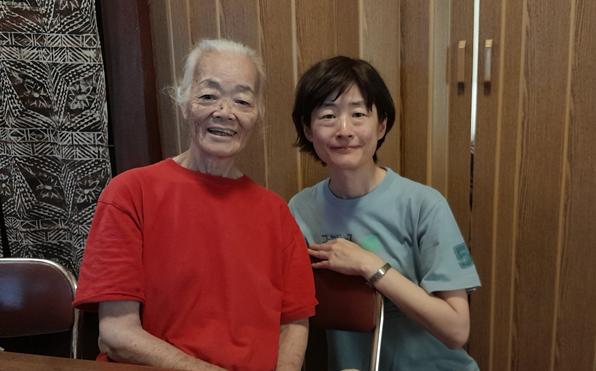

I first learned about Yamazato san through a YouTube video that showed her and her fellow protesters chanting in Ishigaki Port in March 2023. They were protesting against the missiles that had been brought to and installed at the recently constructed Ishigaki Camp without the locals’ permission. In the following year, the documentary film director, Mikami Chie, published the film Ikusa-fumu (The War Clouds), which illustrates how the state-driven fortification efforts since the mid-2010s had gradually and dramatically altered rural societies and landscapes of the southwestern areas of Okinawa, including Ishigaki. Prominent locals are shown in this film, including Yamazato san, who is crucial to native narratives. During my first fieldwork in Okinawa in 2023, I had the opportunity to meet Yamazato san at her home. During a follow-up visit, I attended the documentary film’s premiere screening in Naha. The screening was followed by a talk with the director, where Yamazato san made an appearance as a speaker. Her journey as an activist demonstrates a deep commitment to her native island which runs through her professional endeavors and her personal worldview.

The motivation for Yamazato san’s lifelong commitment to protect island life has been a deep sense of regret. She is from a farming family and after the Pacific War on Ishigaki-jima in 1945, she and her grandmother were the only two survivors of their eight-person family. The years during the post-war American occupation were “another battlefield for survival” (interview with the author in September 2023). Nevertheless, in 1955, she was able to secure a respectable position with the U.S. Military Geology Survey (USGS) as a local field assistant. Leading the survey was female geologist Dr. Helen Foster, who recognized Yamazato san’s strength and appreciated her advice to safeguard the team from natural dangers. In return, the young Yamazato san gained valuable work experiences: She improved her English skills, learned how to collect data, took a jeep to all the creeks on the island and spent some time in Tokyo to finish the colored maps that were to be sent to Washington. Her interests, however, gradually turned towards reviving the traditional lifestyles she had learnt firsthand from her grandmother. These included farming, writing songs in regional ballad forms and recovering the customs of local silk weavers.

Copyright© Nakako Hattori-Ishimaru 2023

In the late 1970s, she was involved in an environmental movement to oppose a plan of new airport construction on the Shiraho Shore, which would have devastated the rich coral reef. While researching the project’s background, she was shocked to discover that the blueprint was based on the geological inquiry she was working on. “I still feel a strong deal of regret for what I did back then. Even though I was working for a salary, I was contributing to a process that would eventually result in the destruction of my native island” (interview with the author in September 2023). She then understood that any significant initiatives for external development on Ishigaki-jima are inevitably linked to military objectives. In 1989, the group appealed to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) to lobby the Japanese Government, whereupon construction of the airport was halted but moved to another location on the island. She considers this to be only a partial victory as their ultimate goal was to stop construction completely.

Yamazato san’s lifelong exposures to various foreign institutions gave her profound ideas for protecting her native land. When I asked her to define peace, her answer was clear: the ability to pass on her inherited way of lifestyle and livelihood to future generations. The quality of peace, she is seeking for, is to preserve her ancestral homeland as intact as possible. Developmentalism is often linked to state-led military buildup in order to counteract rural depopulation. On Ishigaki-shi’s 75th city anniversary, Mayor Nakayama proudly declared in July 2023 that the population had surpassed 50,000, citing the deployment of Camp Ishigaki in addition to general local economic revitalization as the primary drivers (Ryūkyū Shinpō 2023). Countering this dominant discourse of a military-driven economic boom, Yamazato san and her friends warned that the military bases have the potential to take away local autonomy once again. And Yamazato san is aware that many people on the island morally support her group’s protests despite the fact that they appear to be alone when they protest on the street.

References:

Haino, Akira (2022), “Tokushū otome-tachi no sensō 3: Setsu-chan oba no sensō (Special Series: The war of the maidens No.3: Setsuko grandma’s war),” Gekkan YAIMA 334, 6, pp.14-25.

Mikami, Chie (2024), “Ikusa-fumu: Yōsaika suru Okinawa, Shimajima no Kiroku (War clouds: The fortification of Okinawa and its records on the islands),” Tokyo: Shūeisha Shinsho.

Mikami, Chie (2024), “Ikusa-fumu(War Clounds) (Documentary Film)” 2024, https://ikusafumu.jp/ (retrieved on 3 July 2024).

Oaten, James, Lisa McGregor, and Yumi Asada (2003), “There is no end of war for us,“ ABC News, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-02-16/japan-ishigaki-military-base-remilitarisation-counter-china/101869542 (retrieved on 3 July 2024).

Ryūkyū Shinpō, ”Ishigaki-shi no jinkō ga gomannin o toppa”(The Ishigaki City population has exceeded 50,000)” on 10 July 2023, https://ryukyushimpo.jp/news/entry-1744966.html, (retrieved on 9 July 2024).

Nakako Hattori Ishimaru (nakako.hattori2@fu-berlin.de) is a research assistant at the Institute of Japanese Studies at Freie Universität Berlin (FUB) and a doctoral candidate at the Graduate School of East Asian Studies (GEAS). Her main research interests include international cooperation, welfare states, security politics of Japan, war-peace narratives and collective identity formation.