China[1] has been an agricultural society for most of its history (Lardy 1983:7). In the mid-19th century, industrialisation became a desirable target and has been high on Chinese rulers’ agenda since. After 1949, under newly established communist rule, the founder of the People’s Republic of China, Mao Zedong, too, was highly ambitious to lead the country out of backwardness and on a path towards industrialised nations. In order to achieve this long-desired goal, he decided to both step up industrial capacities and simultaneously shift the agricultural production mode from private to collective farming. Collectivisation should enable the state to extract as much grain as possible for unfaltering support of the industry. During his nearly thirty years of reign, the land underwent an unprecedented reshaping of production and distribution routine in the agricultural sector. However, this process was not straightforward featured regional and ideological variations that sometimes gained modest success and sometimes even fabricated huge failures. Eventually, it was abandoned in 1978 after the reopening of the economy and the heralding of a new era of reforms.

In this essay, I first give a brief historical overview of the transformation of agricultural production under Mao. Second, I explore the phenomenon of clientelism in the grain distribution system. Against common belief, clientelism not only exists in corruptive elite levels of society but also flourished during the collectivisation period in the PR China. A special focus is laid on why clientelism played such an important role in the distribution system. For the theoretical foundation of this essay, I mainly draw on Jean C. Oi’s (1989) and Lardy’s (1983) extensive work on collectivisation.

In a liberal, market-driven agricultural system, the state normally plays a bystander role and interferes in the producer-consumer relationship only through taxation, incentives, or business regulations. Contrarily, in a centralised socialist planning system, the state meddles with this relationship by taking over the entire control of production and distribution (Oi 1989:1).

In the wake of Japanese occupation and civil war, extreme poverty and hunger favoured the call for a replacement of the long-established policy of extraction with a new system of production. Based on ideological claims (Scheidel 2018:223), the first land reform (土改tugai) brought brutal expropriation of land from landlords and rich peasants. After 1952, large numbers of previously poor peasants could eventually own a plot of land. A more equalised land ownership, tax reductions, and an economy, which in the early 50’s still was, to a certain degree, incentivised by market demands, resulted in increased agricultural productivity (Karl 2020:118). Lardy (1983:18-19) identifies this kind of economy as “indirect planning.”

A few years later, indirect planning, however, was replaced by “direct planning” (Lardy 1983:19) – a centralized quota system. The central leadership decided to move from privatized farming to a collective production routine with set prices, fixed production targets, allotted field management, and a tight grip on grain distribution in order to fully take control over the entire food production sector. Through this quota system, the non-agrarian, i.e. urban population, should receive optimal support for rapid transformation towards industrialisation (ibid. p.98).

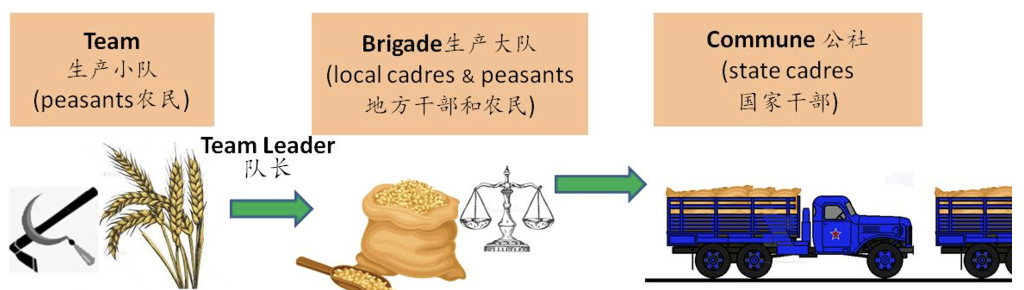

The land that just a few years ago has been distributed among individual peasant families was now collectivised and cultivated by small production teams (生产小队shengchan xiaodui). These mostly resembled naturally grown hamlets or smaller villages. From the teams, the harvest was then transferred to the brigade (生产大队shengchan dadui), where it was weighed and registered. The brigade consisted of local cadres, who mainly were peasants themselves, from the same area, and often team leaders or their relatives. Here, the grain became subject to state control. The transport from the brigade to the commune (公社gongshe) was then in the hands of state cadres, who organised the further distribution. These cadres were not directly related to the local community or involved in the production process. They were on the state’s payroll and acting on behalf of the state. The system of collectivisation was in place from 1956-1960, abandoned for a short period after the disastrous outcome of the Great Leap Forward (大跃进da yue jin), and reinstalled from 1966-1977 (Lardy 1983:19).

| Image 1: Sketch of the production process, marking the friction point position of the team leader. Source: author’s own design |

During collectivisation, the state-society relationship was quite narrowly defined. The friction point, i.e. the point where both entities interact and collaborate, was impersonated by the team leaders (see image 1). At the same time, team leaders were both peasants and representatives of the state. In the brigade, agricultural products were going through their hands – from society to the state (Oi 1989:3). If the peasants needed (or wanted) to retain more grain than was originally allocated to them by the central administration, the team leaders were the appropriate link in the chain to be addressed with this concern (Oi 1989:6). They were the only people who had the means of manipulating numbers and accounts. Hence, maintaining a good relationship with their team leader was essential for the peasants.

Oi (1989:7) identifies this as a typical patron-client relationship or clientelism: both sides benefit from this relationship. They can keep more grain, build mutual trust, and stand shoulder-to-shoulder against an extractive system. Moreover, it served as an appeasing method for dissatisfied team members and could serve as a success story for higher administrative levels. Both sides acted according to their own interests and, at the same time, bypassed the central government’s directive and established a new form of applied policy.

Oi (1989:7-9) regards this as a method of informal political participation. Due to the lack of meaningful forms of participation in communist systems, the masses often seem to have no choice but to build on bilateral personal ties. She even argues that the more stringent and inflexible a system is in its exercise of power, the more chances there are for circumventing the power cascade. On the lowest level of production and distribution, clientelism resembles the prevailing form of socialist reality. As long as there is inequality and a mere top-down approach to addressing this inequality, clientelism will be the natural way of any economic relationship (ibid. p.9).

In addition to the intrinsic clientelism factor in socialist agricultural production, there has been an ideological conflict as well that has kept the peasants reluctant to submit the demanded amount of grain. The fact that, on the one hand, the state deprived the peasants of their right to keep control over their own product (in order to push for industrialisation), but on the other hand, hailed them as the central part of the revolution, encouraged the peasants to think even more of alternative, individual, and informal solutions (Oi 1989:1).

This was exacerbated by the fact that the state would not only, as claimed, extract the surplus grain. In fact, the state demanded all the grain apart from the subtracted portion for fodder, seed grain, and the peasants’ ration, which often was too little. On top of that, the tax system was difficult to assess and often implemented arbitrarily or inaccurately, which increased the pressure on poorer areas or poor peasant families (ibid. p.21-23).

The general reluctance of the peasants and teams to comply with state regulation and the role of the team leader to work as the link between state and society made it a logical consequence to establish an alternative method in order to sideline the socialist quota system in an effective way. The team leaders were relying on a productive team to fulfil the demands from above, but at the same time, they would not dare drive the team to its limits, which was prone to backfire sooner or later. Additionally, he/she was a member of the team as well. The system of clientelism, therefore, proved to be highly effective to juggle with and balance out failures or surpluses.

Clientelism even involved the local cadres on the brigade level as well. The team leaders often sought a client-patron relationship with them, for they, too, belonged to the local community and partially shared a similar destiny with the peasants. After all, the welfare of the teams was part of their responsibility. Moreover, a good relationship with a team was beneficial for them in various aspects, e.g. the provision of rare items or rewards after a good harvest (Oi 1989:125-127).

Consequently, a functioning micro-system was rewarding for the local community in any aspect. It not only put the team in a good bargaining position after a good harvest but also enabled the peasants to keep more grain for themselves after a bad harvest. Given this ‘self-regulating’ character of the clientelism system, it might not be too far-fetched to claim that the existence of this relationship, in its function as a buffer at the lowest level, was a saviour for the entire socialist quota system, even if not deliberately designed as such.

It may be worth further exploring whether or not village-level clientelism is indeed valid for all or most socialist-administered states or only for Maoist China. This has to be considered with regard to cultural characteristics, including religious, political, educational, geographical, or historical aspects. However, the close resemblance with guanxi as well as family ties, as Oi (1989:129) points out, might suggest a certain distinctiveness of the Chinese model.

Conclusively, in Maoist China, the huge transformation of agricultural production from a private to a collective model was initially received with optimism by a large portion of the public. However, with increasing control by the state, questionable implementation feasibility, and unfair and ideologically illegitimate extraction and distribution methods,dissatisfaction over the quota system was one of the main reasons why clientelism on a village level was thriving. Only a system built on personal relationships seemed to enable the peasants to cope with various challenges. However, as Oi (1989:104) puts it, this should not be regarded simply as corruption but as a guarantee for survival and peasant participation (ibid. p.8), which is based on the interests of individual actors and exists parallel to an official economic system.

References:

Karl, Rebecca E. (2020). China’s Revolutions in the Modern World: A Brief Interpretive History. Verso Books.

Lardy, Nicholas R. (1983). Agriculture in China’s modern economic development. Cambridge University Press.

Oi, Jean C. (1989). State and peasant in contemporary China: The political economy of village government. University of California Press.

Scheidel, Walter (2017). The Great Leveler. Violence and the History of Inequality from the Stone Age to the Twenty-First Century. Princeton University Press.

[1] In this context, the term “China” refers to the predominant Han-culture and most parts of the area inhabited by Han-people.

____

This text is part of a series of student contributions from our MA program in China Studies. This contribution was written as part of a seminar on the continuity and changes of poverty (reduction) in the Ming Dynasty and the People’s Republic of China.