by Kazuyoshi Kawasaka and Ami Kobayashi

Rural areas in Japan (inaka) are often thought of as homogenous and “authentic Japan” when compared to metropolises such as Tokyo and Osaka. Metropolitan cities are associated with more diverse and rapidly changing ‘young’ lifestyles, but rural areas in Japan have been also changing due to various reasons. One factor, which we regard as a trigger of societal change in rural areas, is the Japan Exchange and Teaching Program (JET program). The JET program was introduced by the Japanese government in 1987 in order to internationalize Japanese society, including rural areas. According to McConnell (2000), the JET program is Japan’s unique top-down attempt to create “mass internationalisation.” The JET program aims to cultivate international awareness and understanding of cultural diversity in Japan’s local communities through inviting applicants from abroad as assistant language teachers, coordinators for international relations or sport advisors across Japan. Japanese officials called it “the greatest initiative undertaken since World War II related to the field of human and cultural relations,” designed as an international exchange program to change Japanese people’s attitude towards foreigners and foreign cultures by grassroots personal interactions (McConnell 2000: x).

A typical scenery in rural Japan.

Copyright © Ami Kobayashi 2016

Although it was not its intention, the JET Programme has also influenced LGBTQ+ activism in Japan. For example, JET participants organised ‘Stonewall Japan’ in 1995, which was one of the earliest LGBTQ+ groups in the public education sector in Japan and is still active. Although Japan welcomes thousands of young graduates from all over the world for the JET Programme every year, previous studies rarely discussed the difficulties they face in Japan’s rural communities. Some publications discuss the conflict between the “locals” and “foreigners” from a rather dichotomous perspective, but they do not pay attention to the heterogeneity of foreigner’s experiences, especially those caused by their race, sexuality and gender identities.

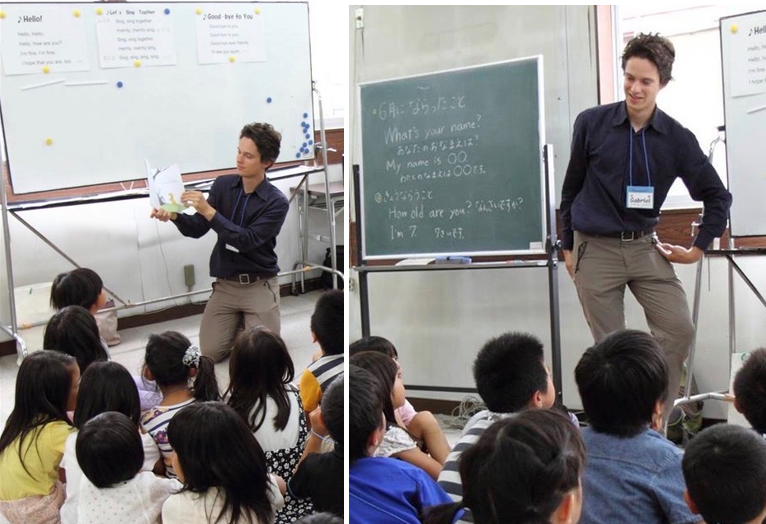

ALTs teach English in Japanese elementary schools, middle schools and high schools.

Copyright © Tono Education and Culture Foundation 2015

In order to examine the difficulties that JET teachers with minority backgrounds face, we conducted semi-structured interviews with former and current LGBTQ+ JET teachers in 2021. They all have worked in rural areas and many of them could not speak fluent Japanese. None of our interviewees had access to local LGBTQ+ communities, and none were actively open about their gender and sexual identity, since they feared that their identities would make their lives more difficult. One of the striking points is that depending on the skin colour and ethnic identity of LGBTQ+ teachers, the problems they faced and how they coped with those situations differed significantly. While white interviewees did not mention their ethnicity, interviewees of colour often referred to their ethnicity as an additional factor entangled with their sexuality that made their work at Japanese schools even more difficult.

One female ALT told us: “I think the, there was a lot of, like, race involved as well. My, the other JETs in the area were all like, you know, blue-eyed blonde and everyone was very friendly with them. But I would like, go to a café with my friend who was black and (…) they’re looking at us like ‘nani (…)’ like ‘what, what is this’, you know. (…) And that’s like not something that I can talk to my coworkers about at all, but also wasn’t something that I can talk about with my, like, JET peers, because they were all white.”(Former ALT, Hispanic, Lesbian woman). But despite the challenges and most of the teaching plan being fixed, most of our interviewees have found ways to make LGBTQ+ visible and tried to tackle heteronormative and sexist presumptions in schools. Through their outlook, worksheets and additional information for English classes, they have negotiated the existing gender and sexuality norms within and outside of the classroom.

In some rural areas in Japan, ALTs are the first foreignerschildren meet and their activities often go beyond simply teaching English.

Copyright © Tono Education and Culture Foundation 2015

In rural areas, there is generally less privacy and people are less tolerant of cultural and sexual diversity, while in big cities, many LGBTQ+ people and foreigners have established their own communities. Japanese LGBTQ+ studies have just started to include LGBTQ+ lives in rural areas into their research and to overcome their metrocentrism as the recently published book “Chihō” to seiteki mainoritī [The “Countryside” and Sexual Minorities] by Sugiura Ikuko and Maekawa Naoki shows. In this sense, the subtle activities of LGBTQ+ JET teachers to expand diversity in rural areas need to be evaluated and further explored. In addition, effective measures should be taken to ensure their safety and mental health in Japan’s rural schools and communities.

References

McConnell, David L. (2000), Importing Diversity: Inside Japan’s JET Program, Berkeley: University of California Press.

Sugiura Ikuko and Maekawa Naoki (2022),“Chihō” to seiteki mainoritī [The “Countryside” and Sexual Minorities], Tōkyō: Seikyū-sha.

Dr Kazuyoshi Kawasaka is principal investigator of the DFG-funded project “Sexual Diversity and Human Rights in 21st Century Japan: LGBTQ+ Activisms and Resistance from a Transnational Perspective” at the Institute of Modern Japanese Studies at Heinrich Heine University in Düsseldorf.

Dr Ami Kobayashi teaches at the Institute of Modern Japanese Studies at Heinrich Heine University in Düsseldorf and at the Institute of History of Education at the University of Kaiserslautern-Landau.

The authors have just published an article about the topic:

Kawasaka, Kazuyoshi and Kobayashi, Ami (2023), “Surviving Under the ‘Hidden Curriculum’: The struggles of LGBTQ+ JET Teachers in Japanese Rural Areas”, Studia Orientalia 124, pp. 145-161.