by Lynn Ng

Maps are not only important for spatial understanding and navigation; they also tell stories across time and serve as memory aids. During my fieldwork in Japan, I arrived in a landscape that offered me no data signal and thus no GPS and no online maps. I was very disturbed. For the first time since my introduction to mobile GPS technology, I had to rely on local maps and signs and my terrible sense of direction to find my way around the countryside. On my third day in the field, I ambitiously attempted to walk to the neighboring village despite the lack of GPS. I walked for over an hour in the direction I thought the village was. I turned off a main road onto a small farm track and then onto a footpath up a hill that I assumed separated the two villages. I followed the ribbons on the trees and the location markers on the path. Finally, I reached a dead end – a sort of plateau where no discernible paths continued. I never found the village. Instead, I took a long nap in the open field until a concerned elderly couple woke me up and pointed me to the closest village – where I had walked from. The couple disappeared into the woods as mysteriously as they had appeared. I often wondered if they had been a figment of an exhaustion-induced lucid dream.

Exhausted, lost and defeated, I took a long nap under these beautiful skies.

Copyright © Lynn Ng 2022

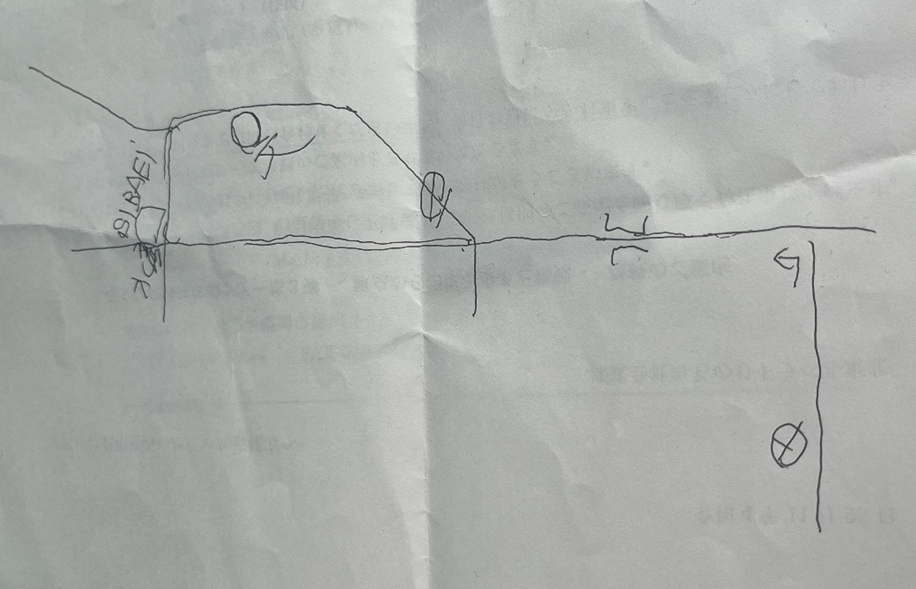

In my next field site, I tried to walk to a distant monument near the reconstruction zone. Even though my GPS was now working, many parts of the Fukushima coastal region have not yet been updated on digital maps. I asked a bus driver about the region – whether it was already walkable or whether it was dominated by construction vehicles. He looked at me, frowned, and asked me for paper and pencil to explain the route. He drew me a map and explained the individual landmarks to look out for. It was drizzling that day. The bus driver asked me why I wanted to visit this place. I explained my research and he told me his story. I was the only passenger on the bus, and during the almost fifteen minutes after the scheduled departure of the bus, the driver described the city – his hometown – to me. I commented on the beautiful reconstructed coastlines. He expressed deep disgust, “You don’t know how it used to be.” He complained about regional politics and about the intended preservation of the monument. I chuckled nervously and he started the bus. After just five minutes of turns around barricaded roads and empty fields, I alighted the bus into increasingly heavier rain. He sighed at my insistence on visiting the monument and wished me luck. I never reached the monument. The rain had become immensely heavy and the roads were occupied by large construction trucks. Before I had even reached the first turn, I was drenched and my shoes soaked despite the umbrella I had in hand. Instead, I sought shelter in a facility nearby, where I, coincidentally, bumped into one of my research participants who was also seeking shelter from the rain.

The map the bus driver drew for me.

Copyright © Lynn Ng 2023

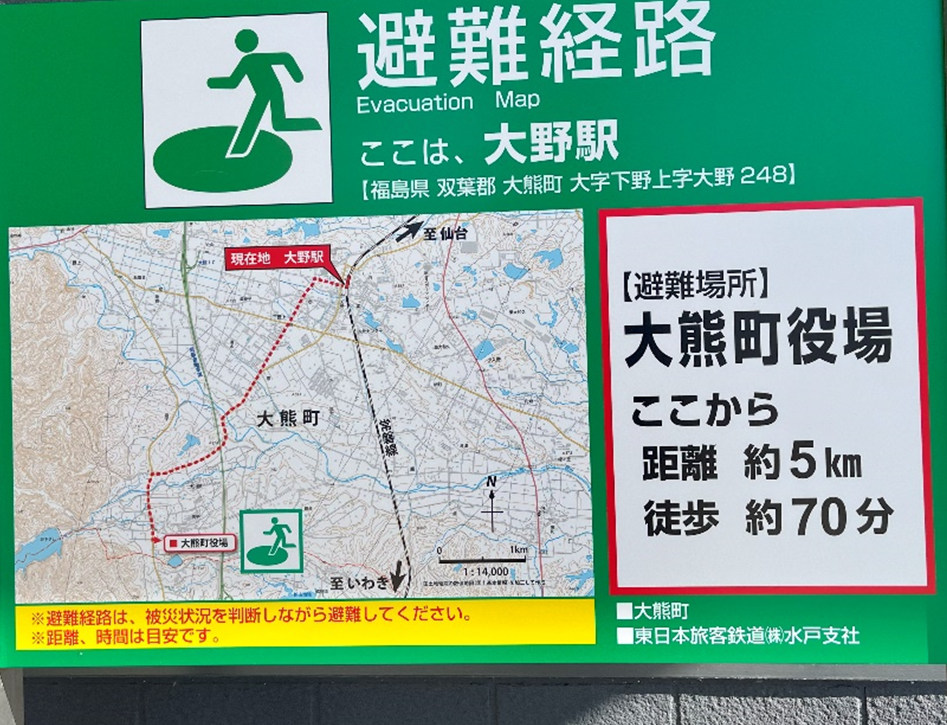

Maps are also often especially important in times of crisis, i.e., evacuation. “Look how silly this is,” one research participant laughed excitedly, pointing to an evacuation sign. From the main train station (Ono) in the city of Okuma, the nearest evacuation point at city hall is five kilometers (or a 70-minute walk) away. She pointed to the distance and joked that we would all die instantly if something happened. I chuckled nervously, not because of the distance and the potential danger we were in, but because of the somberness of her joke and whether it was appropriate for me to make fun of it. She explained to me that City Hall was the first to be reopened, and that subsequently important facilities and plants were built in the region. She showed me her hometown, the barricaded streets, and the upcoming new construction near the train station. People working near the station would have to evacuate five kilometers away in an emergency. I wondered if the Ono Station evacuation map would be updated in the future, and if so, when.

The evacuation map at Ono station.

Copyright © Lynn Ng 2023

Indeed, maps are critical to my understanding and memory of Fukushima and events during fieldwork. I watched as maps were drawn and redrawn at Fukushima to reflect new facilities and new reopenings. Looking back now at Ono’s evacuation map, I recall the emptiness of the immediate area around the station and the isolation of City Hall. I would look back at the bus driver’s hand-drawn map and remember his scowl and concerned eyes for a small explorer traveling in the pouring rain. I would look at the online maps of the mountainous village and realize that all along I had been heading southwest instead of north.