by Cornelia Reiher

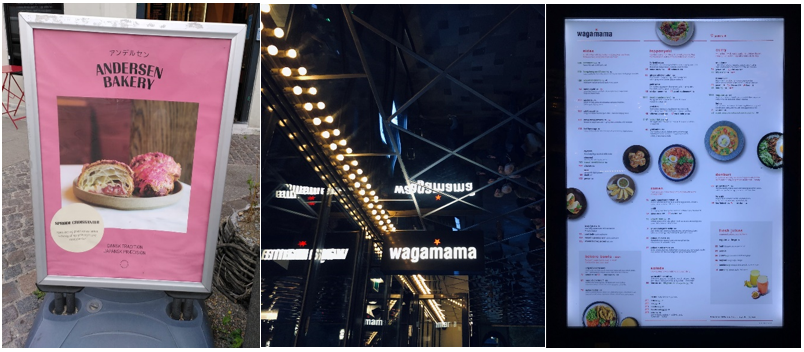

When Covid-19 infections were very low in Northern Europe we seized the chance to leave Germany, where the fourth wave of the pandemic was already casting its shadow ahead in October 2021. Fully vaccinated we were amazed about Denmark where people did not wear masks and where we did not see any of the Covid-19 test centers that were omnipresent in Berlin at the time. Quickly adjusting to the new freedom, we enjoyed Copenhagen’s vivid food culture and visited a number of Japanese restaurants. Copenhagen features a variety of different Japanese eateries ranging from the typical sushi restaurant to high-class fusion cuisine. The city is also home to Japanese bakeries, izakaya, sake bars, ramen restaurants and chain restaurants like Wagamama and Sticks’ n’ Sushi that have branches in other European cities like London or Berlin as well.

Ownership and interior of the different restaurants were just as diverse as in Berlin. The chain restaurant Wagamama in Copenhagen’s Tivoli Gardens, for example, is an example of modern, stylish Japanese/Asian fusion cuisine to be found anywhere around Europe. But we also ate at one Japanese restaurant with Japanese owners and staff. The place was decorated with Japanese art and craft objects featuring tatami mats and chabudai. Guests had to take their shoes off and the waitresses wore aprons. It serves food promoted as authentic Japanese food on the menu and on its website. The restaurant opened in the 1960s and claims to be the first Japanese restaurant in Scandinavia. This type of traditional Japanese restaurant has become quite rare in Berlin where some of the older Japanese restaurants like Daitokai have closed a few years ago.

Not only the interior was traditional. The quality of the food was very close to food available in Japan and the owner told us that they import many of the ingredients. Because they strive for authenticity, they take taste and quality very serious as the following anecdote shows: One member of our group could not finish the sushi she had ordered and asked the waitress whether she could take it home. Instead of coming back with the sushi, the owner approached us and explained that she would not advise us to take it home because it would lose its taste. When my friend insisted, she inquired about how far away she lived, gave exact instructions about how to store it, when to eat it the latest and came back with a plastic bag with additional ice. So, my friend took the sushi into the already quite cold Copenhagen night.

This “sushi incident” shows, what we had already discovered when we interviewed Japanese food entrepreneurs, food workers and chefs in Berlin: Considerations about taste and aesthetics are very important and became a reason, why some Japanese restaurants did not offer food for take-out or relied on delivery services during the two Covid-19 restaurant shutdowns. With regard to take-out, some doubted that the food would still meet their quality standards when warmed up again at customers’ homes. Others did not trust the delivery companies to treat the food in a way that it would still look the same once it had reached the customers. In this regard, the trip to Copenhagen did not only offer interesting and delicious insights into Copenhagen’s Japanese foodscape, but also food for thought about recurring themes like taste and aesthetics of food we have come across before.