by Cornelia Reiher

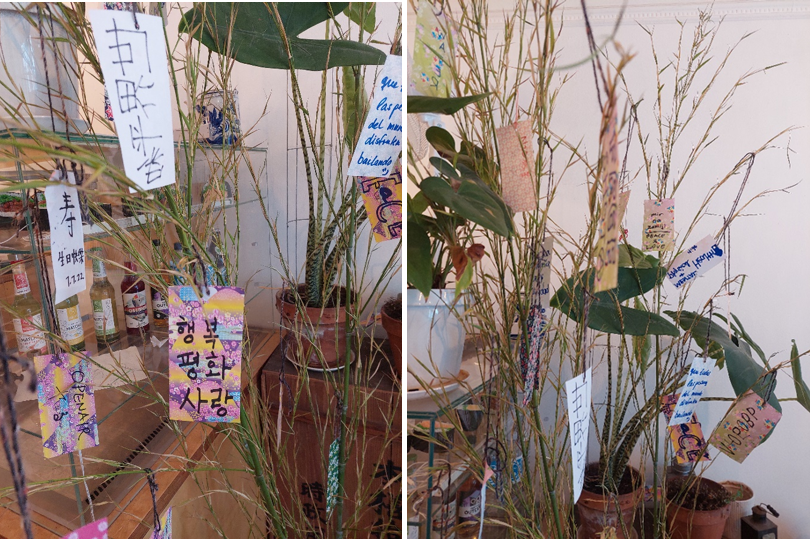

Japanese food is very popular in Berlin, and certain Japanese foods even have their own festivals. In October, I attended the opening of Sake Week and a rāmen festival. Since both events were held on the same day, it was a very exciting day full of interesting sights, delicious taste sensations and exciting encounters with people who are passionate about Japanese food and drink. According to their website, Sake Week is organized by the Sake Embassy, an organization that describes itself as a „liquid meditation movement“. The last Sake Week was held in 2022 in five cities with 50 events, while Sake Week 2023 featured 100 events in nine cities in Germany, Austria, Switzerland and Slovakia.

Copyright © Cornelia Reiher 2023

After we had climbed the stairs to the opening event at a brewery, we were greeted with a “Japanese Radler” made from beer, yuzu sake and lemonade. After a short welcome, we were able to participate in sake tastings from two import companies that offered sake from different prefectures in Japan. The audience that had gathered for the event included people from the restaurant and retail industries, Japanese cultural organizations and their friends and supporters. I met restaurant owners, chefs and sake sommeliers who told me how they pair dishes with sake. They all participate in Sake Week by hosting special sake-themed events at their restaurants and bars. One restaurateur told me that she likes sake because she finds that most of her customers are already attuned to wine and are more open with sake because they don’t know it as well yet. With sake pairings, she has more leeway and guests can make new discoveries.

Copyright © Cornelia Reiher 2023

With different types of sake, fusion finger food and interesting conversations, the two hours went by way too fast and like the sake entrepreneurs who packed up their sake to travel to the rāmen festival, we had to head there too. However, on the way to the rāmen festival, it had started to rain and by the time we arrived, we were completely soaked. Despite the bad weather, there was a long line of people waiting to buy a ticket. Fortunately, we had purchased our tickets online and were able to walk right in. The event was designed as an outdoor event with various booths. When we arrived, people were crowding the few covered seats. Nevertheless, the atmosphere was good and most visitors enjoyed the Japanese food and drinks under the temporary rain shelters.

Copyright © Cornelia Reiher 2023

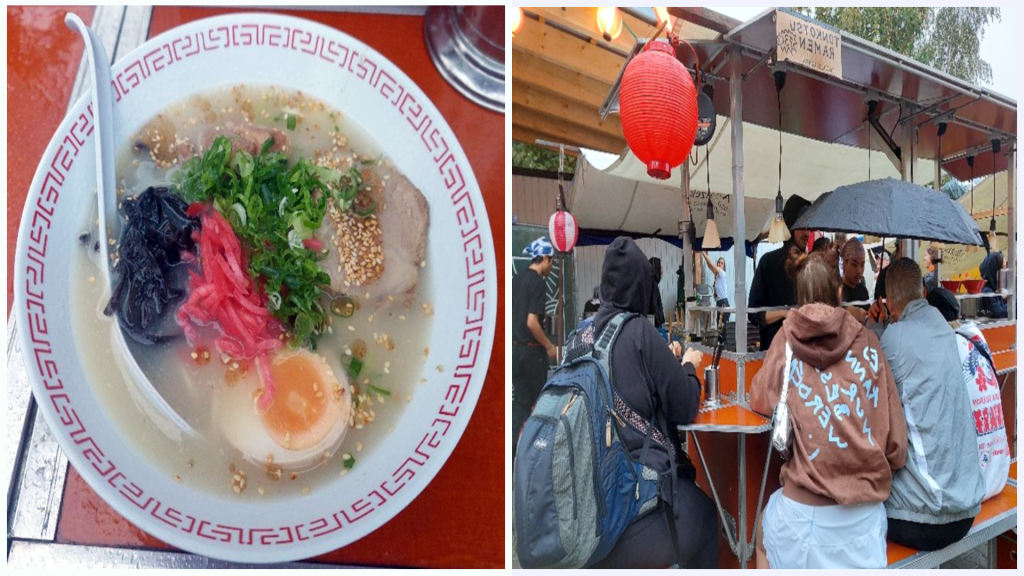

Since we were already wet, we looked around first. In addition to three stalls selling rāmen, there were other Japanese dishes such as takoyaki, taiyaki and okonomiyaki, a sake stall and a stall selling various Japanese handicrafts. One booth was set up in the style of Hakata Yatai. These food stalls are typical of street vendors in Fukuoka, a city in northern Kyushu. The food offered was appropriately tonkotsu rāmen, a specialty from this area also known as Hakata rāmen. The soup broth is based on pork bones and the dish is traditionally topped with sliced pork belly. We got in line and got a seat right by the cart.

Copyright © Cornelia Reiher 2023

While we bravely took our seats outside, most of the guests ordered rāmen to go and ate it under one of the few canopies. We held the umbrella above us and although it was a challenge to hold the chopsticks in one hand and the umbrella in the other, the noodles tasted delicious. Maybe because I had never eaten ramen at a yatai in the rain before. Several young Japanese men and women were working at the stall. Two girls took orders and cashed up, while the other employees prepared the ingredients, cooked the soup and served it. We sat right in front of the containers of ingredients, like eggs and scallions, and I hope my umbrella did not drip into it.

Copyright © Cornelia Reiher 2023

Later it cleared up and more people came to the festival area. But since we were still wet, we decided to look for a dessert and call it a day. We were lucky and bought the last vegan taiyaki with matcha cream and cherries and headed back to the next S-Bahn station, passing supermarkets, gas stations and car dealerships. It was an eventful day, and I was amazed at how many people from very different backgrounds are fascinated by Japanese food and have come just to eat rāmen and other Japanese dishes. At the same time, there is a growing number of non-Japanese entrepreneurs working to promote Japanese food and drink in Germany and I would like to learn more about what drives them.