by Cornelia Reiher

On June 3, we conducted our first onsite interview. We invited Rainer Stobbe from H.I.S. Japan Premium Food & Travel to talk with him about his job and how the H.I.S. Berlin office changed from a travel agency to a shop selling Japanese food during the Covid-19 pandemic. Students had prepared questions in class the week before Rainer came to visit us on FU campus. They took turns asking questions and learned a great deal about handling time constraints, recording and taking notes during an interview. Everybody was particularly delighted because Rainer brought some senbei from the shop.

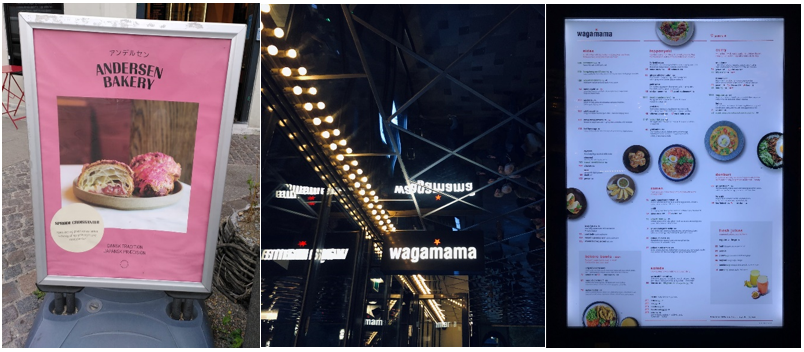

Interview questions covered the shop and its history, customers and products, collaborations with other Japanese food retailers, restaurants and producers, the experience during the Covid-19 pandemic and future plans with regard to food. We learned that the Berlin office is one of three H.I.S. offices in Germany that sell food now. Rainer was hired to build the Berlin branch of H.I.S. It opened in 2019, but when the pandemic hit and travel to Japan was (and still is mainly) restricted, the stores began to sell Japanese food. In Berlin, H.I.S. sells sweets, tea, sake, soy sauce, rice and seasonings. At times H.I.S. also sold Bento boxes produced by a Japanese restaurant from the area and they regularly offer handmade mochi a former restaurateur creates exclusively for the store. Because the shop offers many products other Asian food stores and supermarkets do not sell, many Japanese customers frequent the shop regularly.

The interview provided unique insights into the workings of food retail and labeling and was a great experience in terms of interview practice. It also provided important information students will use for their own research projects about Japanese food in Berlin. This interview was conducted in German, but the interviews to come will be conducted in Japanese. After meeting Rainer, students were inspired to visit H.I.S. Japan Premium Food & Travel and buy some of their favorite sweets and seasonings from Japan we all have missed so much during the travel ban. As long as the future of individual travel to Japan is uncertain, the shop provides a great alternative to those who do not want to do without delicacies from Japan. Thank you, Rainer for coming the long way to Dahlem and for sharing your experiences with us!