by Giulia Noll and Tony Pravemann*

Last week, our class was divided into multiple groups and sent to Berlin-Charlottenburg in order to put into practice the things we had learned about participant observation. The general goal of participant observation is often seen as getting to know a certain community or group of people by spending extended amounts of time with them and partaking in their activities. In contrast to interviewing, participant observation is all about getting to know people over a longer time span and being able to confirm whether their actions correspond to statements they might have previously made. Naturally, other topics are covered in our methods class as well so instead of spending a year or longer observing, we were given the task to walk down Kantstraße and observe a number of different restaurants. Charlottenburg is well known in Berlin as a thriving hub for many Asian and/or Japanese restaurants and could therefore serve as a solid practice environment.

Our group was assigned with three different tasks in total, which consisted of describing each of the restaurants, talking to the people working there and placing an order ourselves. Up to this point, none of us had any experience when it comes to participant observation and so our group started out slightly reserved when it came to approaching restaurant clerks to ask them about their respective stories and experiences working there. We visited three different restaurants over the course of the afternoon, however, we could not enter all of them due to Covid-19 regulations.

Gathering first hand experiences at Shiso Burger (copyright © Tony Pravemann 2021)

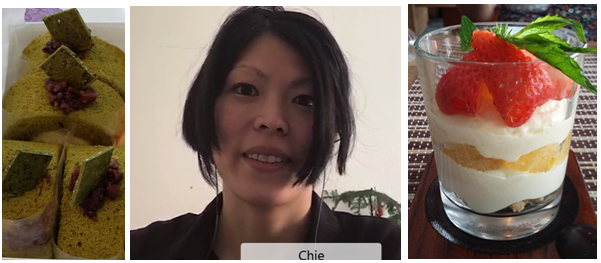

We took a closer look at the restaurants Shiso Burger, Udagawa and XXX Ramen. Shiso Burger and Udagawa have their restaurant names written in katakana and kanji which make them look quite Japanese. However, after talking to the staff of the restaurants, we found that the burger shop and the ramen shop are merely inspired by Japan. In fact, they are owned by non-Japanese and the exterior as well as the interior is simple and modern as in a lot of other restaurants in Berlin. The menu includes not only Japanese but other Asian dishes as well. On the contrary, Udagawa seems to be more on the Japanese side as it offers a full Japanese menu and features a more traditional interior. Unfortunately, we did not have the chance to talk with the staff due to the measures against Covid-19. The different Covid-19 measures were another interesting aspect we could observe. While Shiso Burger and XXX Ramen only asked for registration with the Luca app, Udagawa emphasized safety and hygiene measures by displaying several signs.

A Japanese restaurant at Kantstraße

(copyright © Tony Pravemann 2021)

From our experience, we conclude that participant observation can be a helpful method to discover things that one will not find out by interviews for example. Finally, we would like to say that observing different Japanese/Asian restaurants in Berlin was not only a great opportunity to practice this research method, but also a welcome change after months of online classes.

*Giulia Noll and Tony Pravemann are students at Freie Universität Berlin’s Japanese Studies MA Program.