by Cornelia Reiher

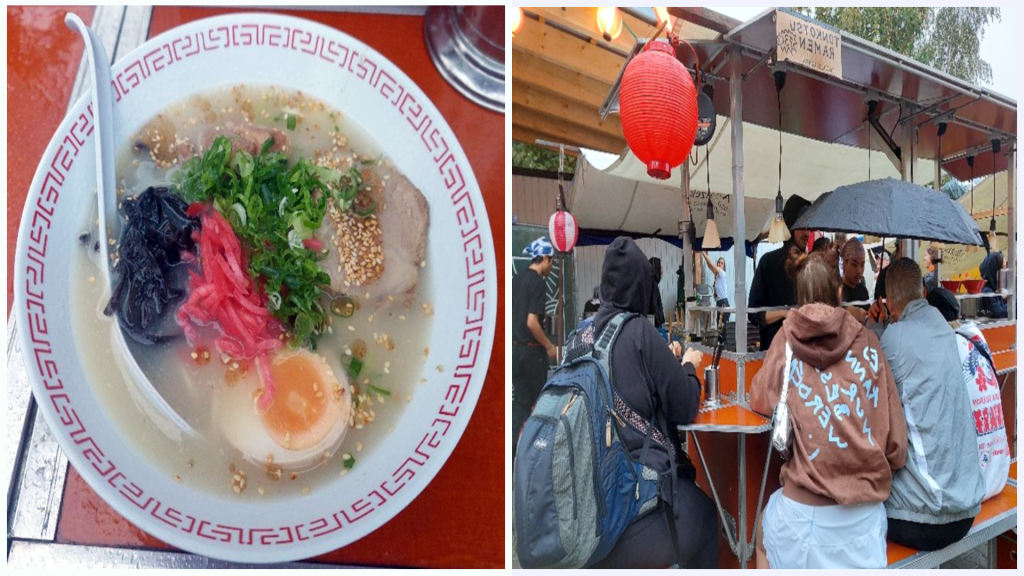

When I talk to Japanese migrants in Berlin, they usually say that they miss Japanese food. Although there are many Japanese restaurants in the city, it is too expensive to eat there every day. Most of my research participants only go out to eat in Japanese restaurants on special occasions. Some take sashimi and other dishes to eat at home, while others never eat at Japanese restaurants. Therefore, in this post, I introduce the everyday eating practices of Japanese migrants in Berlin and where they buy the necessary ingredients to prepare them at home. In 2018, one of our student projects investigated how Japanese exchange students use Asian supermarkets in Berlin. However, Japanese migrants who live in Berlin long-term use many other options besides Asian supermarkets to buy ingredients for Japanese cuisine on a daily basis.

Copyright © Cornelia Reiher 2023

Most of the migrants I have interviewed over the years have told me that they cook Japanese food at home or prepare fusion dishes such as pasta with soy sauce. Some prepare rice and miso soup every day. One research participant told me that onigiri is her soul food, and when Japanese migrants get together, they bring rice-based dishes such as maki sushi. Rice came up in almost all the interviews and conversations I had, and many Japanese migrants mentioned that they bring rice home from a trip to Japan, ask their relatives to send it, or buy yumenishiki rice in Asian supermarkets, even though it is very expensive. Japanese migrants who have lived in Berlin for more than a decade emphasize that it is much easier to buy Japanese ingredients today than it was twenty years ago. The number of Asian supermarkets and online delivery services has increased. Some Japanese foods such as soy sauce or sake are now even available in normal supermarkets. A new Japanese supermarket offering products from Japan has recently opened in Berlin. It offers sake, spices, fresh vegetables and mushrooms, curry pastes, sweets, noodles and more. The supermarket even sells ready meals, just like in Japanese supermarkets, including sashimi and sushi, as well as yakitori, bentō and onigiri. The dishes are freshly prepared in a small kitchen in the store.

Copyright © Cornelia Reiher 2023

In addition to supermarkets, online delivery services provide the Japanese population with frozen fish and other ingredients they need to cook at home. To save some money on delivery costs and because deliveries are often made during the day when most people are at work, some migrants take turns to take orders for their friends in a group order. Sometimes companies that supply fresh ingredients to the Japanese migrant community across Europe organize pop-up events in cities with a larger Japanese community. On these occasions, many migrants come together and enjoy the opportunity to see and choose the products firsthand, meet other people and chat over a hot miso soup. These events are tailored to Japanese customers, the staff speak Japanese, and the information on the price tags is written in Japanese.

Copyright © Cornelia Reiher 2023

Overall, the growing number of places where Japanese food and ingredients can be consumed shows how a culinary infrastructure has developed with the growing Japanese diaspora in Europe. Although more Japanese ingredients are available in Berlin, most migrants emphasize that they are still expensive. Therefore, many migrants make their own miso or nattō at home because they either can’t afford to buy ready-made products or don’t want to spend so much money on them. And some simply enjoy making it themselves. Of course, this is only possible because ingredients such as kōji are now available in Berlin or can be ordered online. This brief overview of where Japanese migrants buy ingredients for home cooking in Berlin shows that the city’s Japanese foodscape consists not only of restaurants and wholesalers that supply restaurants with ingredients, but also of supermarkets and stores where Japanese migrants and the growing number of people interested in Japanese food meet their needs for preparing Japanese dishes at home.