Our team will take a break over the holidays. The blog will be back on January 12. Thank you for following our blog and for supporting our activities. Happy holidays and a happy new year!

Copyright © Cornelia Reiher 2023

Our team will take a break over the holidays. The blog will be back on January 12. Thank you for following our blog and for supporting our activities. Happy holidays and a happy new year!

by Lynn Ng

Digital technologies dominate a significant aspect of our daily lives, and, with infrastructural and regulatory support, hold tremendous potential in promoting Japan’s social and economic growth. Japan’s focus on improving its digital environment and governance is recently most evidenced by the nation’s well-reported organization of the Japan-EU Digital Partnership Council first held on 3 July 2023 [1]. With promises of strategic cooperation in research and development of 5G networks and digital trade principles, as well as data governance and cybersecurity, Japan (as well as the European Union) is arming itself with resources for the new digital society – or commonly referenced as “Society 5.0.”

Other preparations towards Society 5.0 include Prime Minster Fumio Kishida’s announcement of the “Vision for a Digital Garden City Nation” in 2022 [2], thereby kick-starting the rapid transformation particularly of Japan’s rural regions. Rural Japan’s digital transformation since the announcement is increasingly noticeable and has caught the attention of many contributors to this blog. Recent posts on this blog examine the emergence of smart farming, the development of digital human resources, and the potential of digital transformation in Japan’s regions. Followers of this blog would thus by now have a good grasp on what digitalization and digital transformation (DX) are, and what these keywords mean for Japan.

Fukushima is also well onto this trend. As a part of the “Vision for a Digital Garden City Nation,” cities in Fukushima prefecture host several technological and digital research facilities, one of them being the Robot Test Field (RTF) [3] in Namie-town – a town greatly affected by the nuclear disaster of 2011. RTF currently houses incredible facilities that support drones and other un-manned aerospace and deep-space, as well as underwater technological research, among many other cutting-edge technologies. RTF opened in March 2020 amidst the coronavirus pandemic. In January 2023, I visited the RTF facility and spoke with Mr. Sato, a middle-aged mechanical engineer and operations manager of the facility, about the former disaster region’s digital growth. We stood on the roof of the building, me shivering in mid-January chills, as Mr. Sato explains to me what research goes on in the different structures in the vicinity of the main building. Mr. Sato, a returnee to Namie-town, waves at the vast land earmarked for RTF developments that we stood on, and exclaimed how much the region has changed in the last two years.

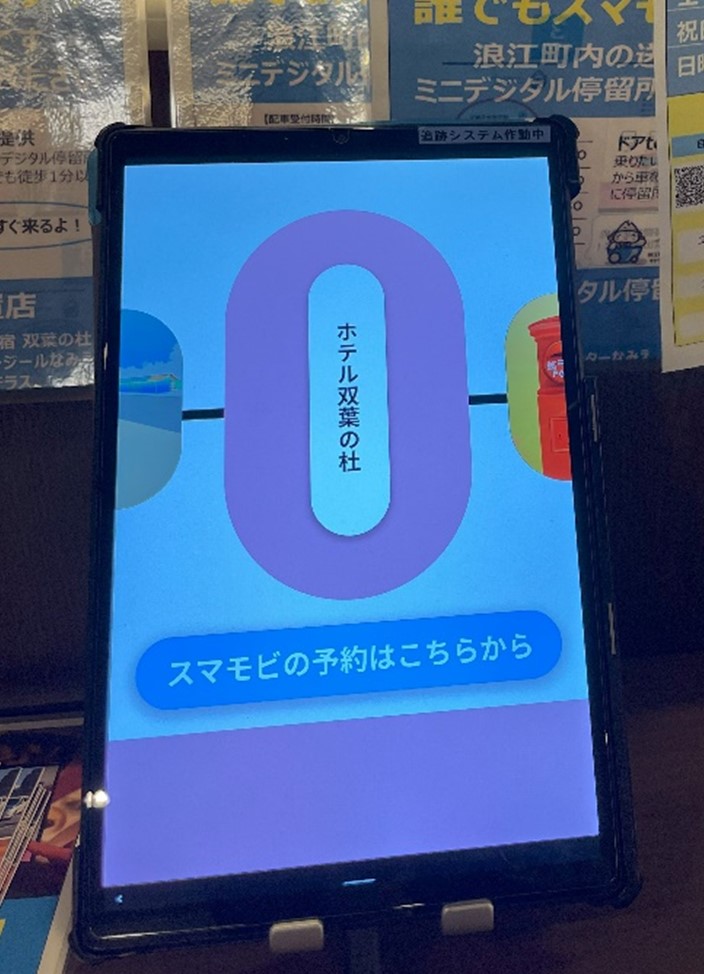

But the technological transformation of Fukushima goes beyond RTF. I encountered new technologies across Fukushima prefecture, such as un-manned convenience stores, automated lawnmowers, and drones. In Namie-town, I was taught by locals how to use the shiny display panels to call for on-demand free taxi services that run across the town [4]. In Okuma-town, I watched municipal officials grab sandwiches and snacks off a shelf that they smoothly paid for using a QR code. Perhaps none of these technologies are as advanced as the deep-space research going on within RTF, but the transformation in behavior is obvious. Locals use digital technologies in their everyday lives in many parts of Fukushima. I asked a municipal officer charging his mobile at one of the many public charging posts, to which he had simply replied: “Ah right, yeah. These are just everywhere here.” Digital transformation of Japan, and any other society, involve not only the establishment of infrastructure and research of new technologies and regulations, but also the uptake of these new technologies by the people. This seems to work well in Fukushima.

[1] Digital Agency. (2023). Japan-EU Digital Partnership Council held. Retrieved online: https://www.digital.go.jp/en/7faa668c-3787-4ff8-934b-093c4d2448c5-en#main-results

[2] JapanGOV. (2022). Vision for a Digital Garden City Nation: Achieving Rural-Urban Digital Integration and Transformation. Retrieved online: https://www.japan.go.jp/kizuna/2022/01/vision_for_a_digital_garden_city_nation.html

[3] FIPO. (2023). Fukushima Robot Test Field. Retrieved online: https://www.fipo.or.jp/robot/en/overview

[4] Nissan Smart Mobility. (2023). Smart Mobility in Namie. Retrieved online: https://www.smamobi.jp/

by Sarah Clay

On a hot day in late August 2023, I take a tuk-tuk from my hotel and make my way to the outskirts of Colombo, Sri Lanka. My driver skeptically asks me if there is some sort of tourist attraction out there, and when we arrive, he waits in the vehicle until I assure him he brought me to the right place. I am here to meet Kanchana Weerakoon and to visit one of her Metta Gardens. The Metta Garden project is part of the Eco Temple Community, a network of Buddhist priests and other civil society groups all over Asia that originates in Japan and engages in environmental activities based upon beliefs of faith.

The Eco Temple Community was founded in 2015 in the context of the Interfaith Climate and Ecology Network (ICE) of the International Network of Engaged Buddhists (INEB). Key figures in shaping the project are Jonathan Watts, associate professor of Buddhist studies at Keio University in Japan, and Rev. Hidehito Okochi. Rev. Okochi is a priest of Pure Land Buddhism and has been involved with a wide range of social and environmental initiatives both in and outside of Japan. Based upon his view on Japan’s destructive economic activities and the 2011 Fukushima Triple Disaster, he turned his own Juko-in Temple and Kenji-in Temple into so-called Eco Temples. Located in downtown Tokyo, Kenji-in makes use of only natural and chemical-free building materials, while Juko-in uses renewable energy gained via solar panels on the roof of the building. In 2015, he initiated the Eco Temple working group to share insights on resiliency activities from Fukushima and on creating Eco Temples in urban Japan [1].

The first Metta Garden in Colombo started as an urban garden close to the office of Kanchana Weerakoon’s organization ECO Friendly Volunteers (ECO-V) [2]. When she bought the plot in 2013, there was only a lonely palm tree in the middle of garbage piles dumped by neighboring households. She explains that there is a connection between the outer environment and what humans have within. “If there is a dirty corner in nature, then that is also where dirty people live. […] But when it is a beautiful garden, more clean, more pure, […] then that is where the most spiritual nature is. Strong energy comes out and the plants are happy. And this is also where more content people are.” [interview Kanchana Weerakoon 25.8.2023] As Metta is the Buddhist concept of loving-kindness, Kanchana wanted to create a place for urban people to come and remember the cosmic relationship they have with the natural world.

When you enter the garden that is ca. 12 x 6 meters in size, you first need to step over a small ditch. After, there is a path made of sharp stones yet, when arriving in the garden soft grass-like plants bring relief under your feet. Kanchana explains to me that this is to remind the visitor that life is a struggle, but that relief can be found in the natural world. The garden is made as a mandala with round plant beddings in all four directions. Each bedding and its plants are connected to an element; tomatoes and peppers represent fire, cabbage water, and the hardness of guava represent the earth. Metta Garden is a sensory garden. The plants are chosen to tickle your senses with their colors, structures, smells, sounds, and tastes. 90% has medicinal properties, and visitors are always encouraged to eat a lot of what they see. In the middle of the garden Kanchana planted a cherry tree that she feels represents herself. She explains to me that in Buddhism the middle is the connection point, it is where you can see both sides. As this cherry tree gives fruits the whole year round, there is always enough for both animals and humans, taking away any hierarchies.

In the days that followed, Kanchana showed me more Metta Gardens that were created in Colombo in the previous years. Some are private gardens, some are publicly owned, but all are designed as a Buddhist mandala and grown without the use of any pesticides. One visit brings us to a home garden in a busy Colombo district of a man who moved to Italy many years ago. He keeps his house as a holiday home and another family lives there to take care of the building in the meantime. Kanchana explains that she created a mandala garden with smaller beddings, so the man can walk through easily and meditate.

Another garden belongs to a newly found center for the empowerment of women. This garden is designed especially as a fruit and vegetable garden, to provide healthy food to pregnant women and children amidst Sri Lanka’s persistent economic crisis. There are various moringa trees, guavas, and banana plants as well as all kinds of nutritious vegetables. A sunflower blooms in the middle of the mandala, representing joy and happiness.

Kanchana’s Metta Gardens are indeed small spaces of joy and happiness in a highly urbanized environment. What I find so fascinating is that it is never only about the environment; the idea is that by nurturing the outer world, also the inner world gets nourished. Thus, while Metta Gardens are a reaction to the environmental degradation that is so present in Colombo these days, they are equally created to positively contribute to Sri Lanka’s social issues. This challenges the conceptual dichotomy of society and the natural world. Metta Garden also illustrates that projects that are part of the Eco Temple Community are always transnational and local at once. All projects share an understanding of Buddhist concepts and the tasks that religious practitioners have in this world. Although originating in Japan, these forms of knowledge are translated differently in the various sites according to the social and environmental needs that exist on the ground. As such, they provide insights into the ways in which religious traditions gain different meanings and practices according to time and place.

[1] website Eco Temple Community Development Project https://eco-temple.net/

[2] website Eco-Friendly Volunteers https://eco-v.org/metta-garden/