The summer term ends in Berlin and we will go on a vacation. We will be back with more posts about rural Japan on August 19. Have a great summer!

Copyright © Cornelia Reiher 2015

The summer term ends in Berlin and we will go on a vacation. We will be back with more posts about rural Japan on August 19. Have a great summer!

by Marius Palz

When riding your car along the east coast of Nago City you will pass several small villages that lie north of Cape Henoko, a place that became mostly known for the ongoing construction of a new military facility, yet another one of many American bases that are cramped together on the small island of Okinawa. The small villages north of Henoko are what I consider my field site. While Henoko has been the focus of many academic and newspaper articles, not much attention has been paid to these small villages in the north, although they are also affected by the controversial base construction. They are also interesting to look at from the perspective of urban-rural migration.

Passing through these villages, you will see the turquoise waters of the inō (inner reef section) on the one side and the green mountains of the yanbaru (forested area of northern Okinawa Main Island) on the other. It is a truly idyllic place, but you will also see many abandoned houses similar to those in other parts of Japan. There are several reasons for the population decline over the last decades, some of which I want to address here.

The area of Nago’s east coast is called Kushi, which invites a play on words in the local language: “Kushi wa kushi ni natteiru”. The first kushi in the sentence refers to the area while the second one means “last” or “behind” in Uchināguchi (the language of Okinawa Main Island). “Kushi comes last” is a common saying among those who live here, referring to the late introduction and poor maintenance of what is considered essential infrastructures like water, roads, coastal armouring and internet. Compared to the urban southern part of Okinawa Island, Nago City is already considered underdeveloped, especially with regard to the availability of jobs for young people. The villages of Kushi, however, could be seen as the periphery of the periphery. The number of schools along Nago’s east coast declined drastically over the last decades leaving the villages north of Cape Henoko with one facility that combines elementary and junior high school as well as one senior high school. With only a couple of job options, such as local schools, roadside shops or the local fisheries association, many young people decided to leave their home villages to build up a life in the urban south or in major cities of mainland Japan.

Many have left this beautiful place, but they did not give up on their inherited property, which poses another problem for the villages: even though there are multiple abandoned houses, newcomers that would like to live in this remote place cannot move in. My interlocutors explained to me the reasons for this: Okinawa has a strong tradition of ancestral worship, which is represented by the family altar, normally located in the house of the oldest son. Moving the family altar is extremely costly because ritual specialists have to get involved. Moving it would also break the connection between the family and the ground passed on over generations. Therefor most people leave the family altar behind when moving to the city and visit it during days of worship. The presence of the family altar makes it impossible to sell the property or rent it out to strangers. To be able to do so consent within the family must be obtained, which is difficult since Okinawan families tend to be very big. Instead of renting or selling, some families prefer to tear down the house and construct little concrete huts to house the family altar.

Among those who stay in the villages of Kushi, some decided to work on the base construction site. Despite massive protests against the project that have been going on for over two decades now, the Japanese government insists on Henoko being the only possible location to host the base. Of course, the construction generates jobs, but it also comes with severe environmental consequences as well as noise pollution and possible accidents in the future, leaving those who depend on an income from base construction with mixed feelings.

Meanwhile, some of the villages still manage to attract urban migrants despite all the problems mentioned above. The combination of clear waters and forested hills make Kushi an attractive area for those in search of an alternative to Naha, Tokyo or Osaka and collective village activities create a sense of belonging. Especially those places that emphasize communal work and festivities attract new people. The Covid-19 pandemic, however, made these activities more difficult. Formerly harvest festivals, communal dances, sports events, collective village maintenance and barbecues on the neighbour’s porch were good occasions for newcomers and long-time residents to mingle. It is hard to build up ties when all of these events get cancelled year after year.

Marius Palz is a member of the ERC-funded “Whales of Power” research project and a PhD candidate at the Department of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages (IKOS) at the University of Oslo. After having worked with members of the Ainu community in Hokkaidō and Tōkyō for his Masters, he is currently writing his dissertation on “Human-Dugong Relations and Environmental Activism in the Ryūkyū Archipelago.” As an anthropologist of Japan, he is not only interested in minority-state relations, but also multispecies and extinction studies. He conducted eight months of fieldwork in Okinawa during 2021, most of which he stayed in the Kushi area.

by Johannes Wilhelm

It is the end of February 2020. From my wooden house at the southern foot of the inner volcanic cone of the huge caldera of Aso (Kumamoto Prefecture), I am heading for Tokyo, where I will give a lecture on the “Cowboys of Aso”. Before departure, I check the latest mails. The organizer mails that in view of the beginning pandemic and in agreement with the Japanese authorities all events at the institute have to be cancelled at short notice. Well! I stoically took note of the decision, but on the plane the sense of my outward and return flight seemed quite absurd. After a few days, I was back at the volcano, while at the first shopping in the only supermarket of Minamiaso, surprisingly, neither official trash bags, nor toilet paper was to be found: everything bought empty. I asked my relatives and friends in Tokyo and elsewhere if this was also the case there, but they were all surprised, because everything was still available. The following week, however, some of them came forward and told me that a run on toilet paper had now also begun in the other major cities of Japan. Then – about two weeks after Aso – I read in the foreign media that, in addition to toilet paper, noodles were also becoming scarce. At that time I remembered the lyrics of a song by the German band Tocotronic about the new strangeness, which opened up to me like the discovery of a new semiotic continent … https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZweXZqoV7nc&ab_channel=OMhA

Minamiaso thus became a trendsetter in terms of social phenomena in the pandemic, at least as far as toilet paper was concerned. And the trash bag shortage soon died down, too. Later, other oddities in the countryside came to light, such as alcohol dealers who out of the blue marketed their whiskey or shochū as disinfectants, or some greenies trying to sell overpriced masks of dubious origin at moon prices, but I want to focus on other things in this text.

Many people with an affinity for Japan are probably aware that the Aso region is one of the main tourist attractions on Kyūshū Island. It occupies a correspondingly prominent role in local economic life, although in my opinion the main pillars of the economy are the welfare sector (keyword: aging) in addition to agricultural production. An important fact is that the working life of many people in Aso consists of several parts. For example, many rely on their land holdings to pursue a primary activity such as cattle raising or rice cultivation, while also pursuing a few side jobs, such as cleaning public baths in the evenings or producing handicrafts such as embroidery, woodwork or pottery offered at michi no eki or other outlets. Full-time jobs are only those in the administration of the city hall or government offices and schools as well as full-time positions in production facilities in the industry. The structure of the tourism sector is similarly diverse. The domestic tourists, but mainly those visiting from abroad, usually only see the hotels, restaurants or inns, i.e. the superficial manifestations of the industry with their many employees, but behind them there is a whole range of sub-enterprises, such as dry cleaners for bed linen.

Just a couple of weeks before the so-called “Golden Week”, it was decided that all public baths and the onsen thermal baths, which are extremely popular among tourists, would be closed for an indefinite period. Lodgings and restaurants were also ordered by local authorities to take a rest period. When I went to the nearest dry cleaning business in May to prepare my winter clothes for proper storage over the humid summer, I was told that from now on the business would only run on Saturdays every fortnight and only a quarter of the staff – mainly full-time employees – would still be present, as there was no demand in the light of the closed lodges.

… to be continued …

Johannes Wilhelm is an independent researcher and is affiliated with Vienna University. His main studies focus on the relationship between nature and society. His interests include fisheries, pastures in mountainous regions, and rural areas as much as general phenomena in society such as radicalism, migration and social vulnerability.

by Lynn Ng

As a child, whenever I complained about Singapore’s horrible heat and humidity, my parents would show me pictures of snowscapes. “Mind over matter,” they always said. I never believed in the “science” behind my parents’ actions, because those pictures only ever made me feel envious of people who do not live in the tropics and never any cooler than before. Yet, this week as I sweat through yet another T-shirt in Berlin, I decided to look up the photographs of my time in snowy Hokkaido for comfort in this hot time. Along with this decision came a strong nostalgia for this region I once called home.

In 2015, I transplanted myself from tropical sunny Singapore to a rural town that buries itself in over 200cm of snow every winter. I enjoyed the snow – the softness and refreshing cold that comes with it. But more than snow, I relished the quiet rurality. Rural Japan, and especially rural Hokkaido, is beautiful. Like most urbanites in rural Japan, I arrived with rose-tinted glasses. Everything in the countryside was wonderful – the untouched nature, the friendly people, the countless cheap hotsprings… the list goes on.

Over the years, I would notice how tinted these glasses were for rural Hokkaido is of course not without its problems. There were moments when I wanted to catch a movie in the theaters only to realize the nearest showing was in a city two hours away. The train there would arrive at either 8 a.m. or 4 p.m., or would be cancelled in case of snow. Such trivialities aside, I saw also the underutilized theme parks and landmarks built with private funds during the bubble or supported by government funds for rural revitalization. Many local residents complained to me that these projects were a waste of money since no one goes there, and yet these parks were some of my favorite places to visit for the additional quietness.

Let us also not forget that rural Hokkaido also has plenty of snow, and with it comes the art of yukikaki (snow shoveling) that is the pride of Hokkaidoians – the Dosanko. Much like household chores, yukikaki is a mundane activity many Dosankos do especially in the wee hours of the morning. Dosankos have repeatedly told me that yukikaki was a means of boosting work ethic and instilling discipline in children. I once met a family who chose to start a farm in Hokkaido because they thought it would instill the best work ethic in their children – something urban cities or other rural places in Japan could not offer because of the extra activity of yukikaki. For three years, I simply found yukikaki a chore.

Perhaps I never had good discipline to begin with, nor particularly strong work ethics by Japanese standards. Or was it because I never did yukikaki and thus have no discipline? Which came first? And for this, every winter I was reminded of being the “outsider.”

Indeed, rural Japan and rural Hokkaido carries with it its own set of problems. As I reminisce about the goods and bads of my three years in there, I can only proudly say that I regretted nothing of it. Perhaps my glasses are still rose-tinted till today, or perhaps there is something truly enticing about rural Hokkaido that one cannot simply let go of despite all of its problems.

by Shilla Lee

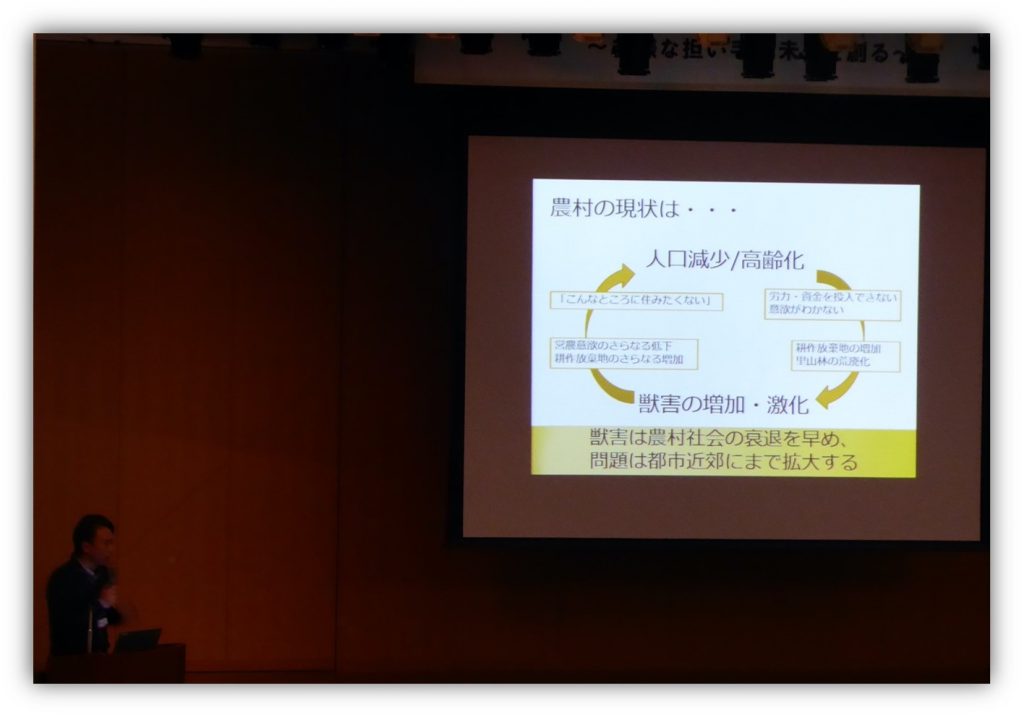

Recent studies on regional revitalization movements in Japan have explored various local initiatives to mobilize the urban population to rural areas (Klien 2020; Manzenreiter et al. 2020). While they provide us with rich contexts, the discussions seem to revolve around an essentially anthropocentric account of regional sustainability. I want to bring attention to my rough ideas about a new perspective to scrutinize the social implication of regional revitalization movements in Japan: to broaden our discussions beyond the human-human domain by exploring problems of depopulation within the wider panorama of human-wild animal (pestilence) relations.

There have been growing cases of wildlife damage in depopulating regions across the globe. Let me briefly mention an article published by The Guardian in January 2021 (Flyn 2021). It talks about how declining fertility rates have led to serious social problems in wealthy countries like Germany and Japan. However, rather than focusing on issues of birth rate per se, the discussion develops into changing human-animal relations in scarcely populated regions. Highlighting a case of akiya (empty house) in Japan, the article directs our attention to how abandoned farms and gardens are reclaimed by wild animals due to an absence of human existence and how we should be more serious about the contrasting state of shrinking human population and prospering wildlife.

In this context, I suggest that we expand our notion of regional revitalization to non-human beings and question whether regional ‘re’vitalization also implies a power ‘re’distribution between humans and wild animals. When discussing rural social problems such as depopulation, aging, and declining local economy, they are dealt with as issues of human society, precluding social and physical spaces shared (or fought over) with non-human beings. We need to think about whether various strategies that attempt to pull in (attract) the human population such as migrants, tourists, and foreign workers to rural regions also pushes away wild animals that are wandering around once human-dominated habitats. As recent studies on human-wild animal (pestilence) relations show (Enari 2021; Enari and Tsunoda 2017; Tsunoda and Enari 2020), remote village communities lack human forces or community spirits to protect crops from wild animal damage and tensions rising from such conflicts lead to increasing practices of wildlife pestilence to control their population.

The prosperity of wild animals beyond human control “can appear a threatening development that points to the retrenchment of human society rather than a benign revival of nature” (Knight 2003:236). Moreover, at a municipal level, increasing conflicts with wild animals not only create economic damages but also undesirable images of rural livelihood, thereby, affecting key strategies of regional revitalization policies that focus on domestic tourism and urban-rural migration. As Knight points out “the impact of the wildlife pest is not confined to the material damage it causes to individual farmers and foresters but extends to its negative symbolism vis-a-vis the community as a whole” (2003:237). As much as rural areas are relying on incoming tourists and migrants for their economic and social sustainability, any source of negative images poses challenges. In this sense, regional revitalization is not only a matter of increasing the human population but also of adjusting human-wildlife relations.

Let me briefly illustrate Wildlife Damage Forum that was held in Tamba Sasayama during my fieldwork in 2018-2019. One of the main actors that dealt with problems concerning wildlife damage in the region was an NPO named Satomon. According to what is written on their official webpage, their key concern is the “wildlife pestilence problem” (jyūgai mondai) by monkeys, deers and wild boars that threatens a Satoyama lifestyle. They argue that wildlife damage takes away the joys of harvesting by referring to young people who move to rural areas and then give up their dreams of living a peaceful country life: “Young migrants who are fascinated by the countryside and relocated to work on farms also said, ‘I cannot work the fields in such a place’ and are giving up their dreams and leaving the villages” (nōson ni miryoku o kanji, ijūshite shinki shūnō shita wakamono mo,” konna tokoro de nōgyō wa dekinai” to yume o akiramete mura o satteiku). It is in this context that Satomon suggests what they call the “wildlife pestilence measure” (jyūgai taisaku) and organizes Wildlife Damage Forum as one of their key initiatives.

An event for the year 2019 was held on a cold day in December in a shimin sentā (citizen center) in Tamba Sasayama. Following an opening speech by the mayor, representatives of various local organizations addressed their ideas to tackle the growing damage by wild animals. A group of social scientists first pitched a behavioral observation of wild boars in the region to examine what kind of damage prevention mechanisms would work. The next speaker demonstrated how the aging community and wild animal damage should be thought of together. Lastly, a group of local middle school students presented a school club activity that produces coin purses from leathers of wild deers. What I found interesting was how they all began with an emphasis on the importance of living with wild animals, however, sought co-existence through curtailing the population growth of the latter. For instance, the business idea presented by the middle school students to rethink human-wild animal conflicts as a way to make profits from the latter was premised on the legitimacy of wildlife hunting and other measures to eradicate the overpopulation of deers. Similar ideas were found in local restaurants that promoted wild boar meats as a local delicacy and a wild meat processing business started by a recent urban-rural migrant. Wild animal damage was being cope by residents by reframing it as a source of economic prosperities and attractive elements of the region.

References

Enari, Hiroto. 2021. “Human-Macaque Conflicts in Shrinking Communities: Recent Achievements and Challenges in Problem Solving in Modern Japan.” Mammal Study 46 (2): 115–30.

Enari, Hiroto, and Hiroshi Tsunoda. 2017. “Emerging Wildlife Issues in an Age of Large-Scale Human Depopulation—Introduction.” Wildlife and Human Society 5 (1): 1–3.

Flyn, Cal. 2021. “As Birth Rates Fall, Animals Prowl in Our Abandoned ‘Ghost Villages.’” The Guardian, January 24, 2021.

Klien, Susanne. 2020. Urban Migrants in Rural Japan: Between Agency and Anomie in a Post-Growth Society. State University of New York Press Albany.

Knight, John. 2003. Waiting for Wolves in Japan: An Anthropological Study of People-Wildlife Relations. Oxford University Press.

Manzenreiter, Wolfram, Ralph Lützeler, and Sebastian Polak-Rottman. 2020. Japan’s New Ruralities: Coping with Decline in the Periphery. Routledge.

Tsunoda, Hiroshi, and Hiroto Enari. 2020. “A Strategy for Wildlife Management in Depopulating Rural Areas of Japan.” Conservation Biology 34 (4): 819–28.

Shilla Lee is a PhD candidate at Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology in Halle, Germany. Her research focuses on the notion of rurality and creativity in regional revitalization practices and the cooperative activities of traditional craftsmen in Japan.