by Chris McMorran

Kurokawa Onsen is a rare bright spot in Japan’s countryside. Since the mid-1980s, it has become one of the country’s best-known hot springs resorts. Prior to the outbreak of Covid-19 and its disastrous impacts on tourism worldwide, this tiny village of a few hundred permanent residents annually welcomed nearly a million visitors who soaked in the springs, purchased souvenirs, stayed at inns (ryokan), and enjoyed the rural landscape.

Copyright © Chris McMorran 2012

Located in the center of Japan’s third-largest island, Kyushu, Kurokawa features a few dozen inns, shops, cafes, and homes gathered along the Tanohara River. There is no railway access, so all guests arrive by car or bus on winding mountain roads. Depending on the season, Kurokawa is covered in snow, exploding with the colors of flowers and foliage, or cooler than the sweltering cities below. For most of the year, however, it floats in a sea of green. Straight rows of plantation forests, primarily Japanese cedar (Cryptomeria japonica, or sugi), line the hillsides, while in the heart of the hamlet, mixed deciduous and coniferous species stand amid flowering shrubs that envelope structures and decorate roadsides. Dark wooden signs with Japanese and English script point to businesses, and all buildings follow a similar pattern: built one to three stories high and painted beige or dark mustard, with black roofs and trim. The overall effect gives Kurokawa a timeless quality; vaguely traditional, but not from any specific era.

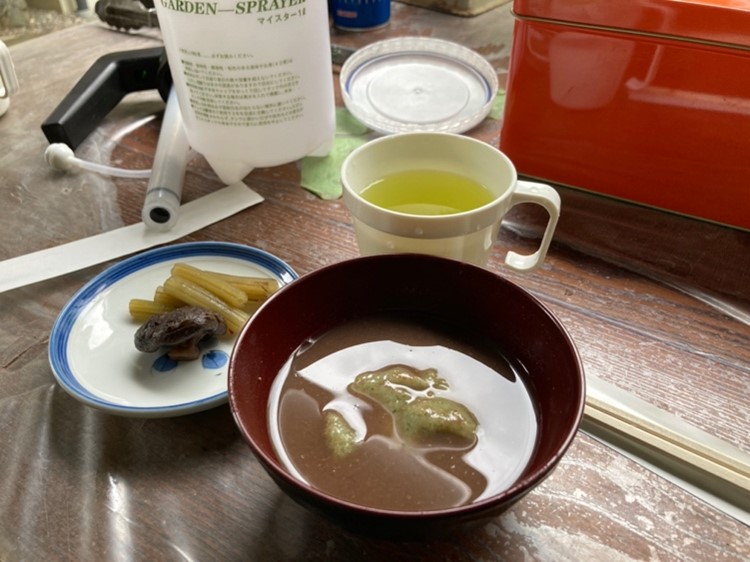

Most visitors begin at the tourist information center, where they collect maps and ask which outdoor baths to try. Since the late 1980s, the resort’s unique selling point has been a wooden pass, called nyūto tegata, that allows entry to three outdoor baths (rotemburo) at any of the 25+ inns. Between baths, visitors stop by the shop selling locally distilled spirits or café that sells cream puffs, all while photographing themselves next to the tree-lined river and in front of the picturesque inns and shops.

Copyright © Chris McMorran 2012

In addition to tourists, Kurokawa has attracted academics, planners, landscape architects, designers, and this Geographer. From 2006-07 I worked at a handful of inns (ryokan), washing dishes, scrubbing baths, and vacuuming tatami mats. In fact, I often welcomed guests and accompanied them through this landscape for the first time. At one inn I drove guests from the bus stop to our inn. My passengers frequently commented that Kurokawa was so nostalgic (natsukashii) and that it felt wonderful to be surrounded by nature. At another inn I swept the paths and parking lot and greeted guests. As I carried luggage through the tunnel of trees to the lobby, guests remarked how lucky I was to work in this beautiful landscape.

Copyright © Chris McMorran 2006

In 2007, Kurokawa even received the Japan Institute of Design Promotion’s “Good Design Award,” in recognition for its nostalgic village landscape that “at a glance appears undesigned” (S&T Institute of Environmental Planning and Design 2008, p. 34). In fact, this landscape has been carefully designed to give this effortless appearance. And the efforts are continuous, through activities like tree-planting and design principles established and followed by local business leaders. I have written about these efforts elsewhere, including how, through their active landscaping, local residents embody the rural ideal they aim to produce for tourists (McMorran 2014).

I consider this landscape evidence of the potential of rural Japan to revitalize and thrive in the future. At the same time, I find this landscape problematic for how easy revitalization seems. I put it this way: “Kurokawa’s landscape narrative implies that Japan’s twentieth century story of rural depopulation was not the result of the systematic prioritization of urban development at the expense of the countryside, and that any rural village could be revitalized if only residents were sufficiently cooperative, interdependent, hard working, and innovative” (ibid., p.13). The reality, of course, is that not every village that hopes to revitalize can reproduce Kurokawa’s success. Every place will face unique challenges and must design its own future, and larger structural forces – continued out-migration, demographic decline, increased risk of natural disasters due to climate change – will make revitalization increasingly difficult.

References

McMorran, C. 2014. “A Landscape of ‘Undesigned Design’ in Rural Japan,” Landscape Journal. 33(1), pp. 1-15.

————– 2022 (Forthcoming). Last Resort: mobilizing hospitality in rural Japan. University of Hawai’i Press.

ST Kankyō Sekkei Kenkyūjo. 2008. Kurokawa Onsen no fūkeizukuri (Total landscape design of Kurokawa Onsen).” Fukuoka: ST Kankyō Sekkei Kenkyūjo.

Chris McMorran is Associate Professor of Japanese Studies at the National University of Singapore. He is a cultural geographer of contemporary Japan who researches the geographies of home across scale, from the body to the nation. His is the author of Ryokan: Mobilizing Hospitality in Rural Japan (2022, University of Hawai’i Press), an intimate study of a Japanese inn, based on twelve months spent scrubbing baths, washing dishes, and making guests feel at home at a hot springs resort. He also co-produces (with NUS students) “Home on the Dot,” a podcast that explores the meaning of home on the little red dot of Singapore.