by Sarah Clay

Since the beginning of the 21st century, the Japanese government has encouraged rural areas to develop local brands as part of their revitalization strategies. To attract tourists and migrants from urban areas, rural municipalities and their residents receive support to develop products unique to that region. This resulted throughout Japan in an enormous increase in local products over the past two decades [1]. Some famous examples are the melons from Yūbari town, apples from Nagano, and wine from Yamanashi Prefecture. On the Miyako Islands, you can find all kinds of products made with local herbs and plants. Popular, for instance, is the sweet-scented getto tea, purifying noni soap, and Yarabu Oil that is made by the elderly on Ikema-Jima.But even more than local delicacies or beauty products, it is the sea and its unique color known as “Miyako Blue” that attracts Japanese tourists and migrants the most. In this blog post, I introduce two producers who have turned the sea into a commodity and developed a product that offers tourists and others new ways to experience the sea of Miyako.

Copyright © Sarah Clay 2022

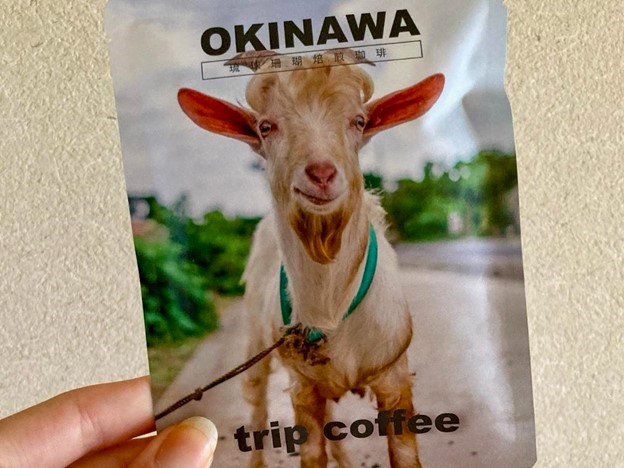

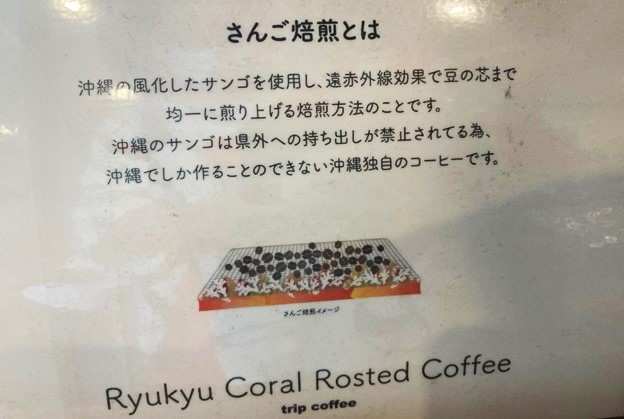

The first product is not produced in Miyako, but sold in local stores and in the umi no eki of Irabu-jima. 35 Coffee (pronounced: san-go coffee, sango is the Japanese word for coral) is an Okinawan coffee brand that was founded in 2009. The special thing about the coffee is that the beans are slowly roasted at a temperature of around 200 degrees Celsius on coral fossils from the Okinawan Sea. According to the prefecture’s fishing law, it is strictly forbidden to collect corals or coral fossils. That is why 35 Coffee works with a company that has obtained a special license for this purpose. It is also forbidden to export coral from the prefecture, so 35 Coffee can only produce on the islands of Okinawa – which the company uses as a unique selling point. You can buy the coffee via the company’s website, in local stores and in the two 35 Coffee stores on Kokusai Dōri in Naha and in Okinawa World in Nanjo [2].

Copyright © Sarah Clay 2022

Besides using corals in the production process, 35 Coffee donates 3.5 percent of its profits to coral restoration projects. Their main partner is Okikai, a construction and real estate company that also specializes in coral transplantation. Coral transplantation has become a popular conservation method in Okinawa in recent years. First, a healthy host coral is taken from the ocean and divided into several pieces. These polyps are kept in a water tank and monitored until they reach a size when they can be planted back into the ocean [3]. Okikai does this in April and October, as the company realized that survival rates are highest during those months.

Copyright © Sarah Clay 2022

Another product that is being sold on the Miyako Islands is the salt of the brand Kanashaya. Kanashaya means “lovable” in the Miyako language. The handmade salt is extracted directly from ocean water gathered at the Yabiji coral reef, a designated natural reserve that is located a little off shore of Ikema-jima. The producer of the salt, Bibi-san, started the Kanashaya project during the COVID-19 pandemic when she was in need of some extra income. The salt can be bought via her online shop and in local shops and restaurants on Miyako. It can be either used for consumption or mixed with water as a body scrub [4]. There are different variants of Kanashaya salt. The water of Yabiji is collected either during full moon or new moon, with the moon standing every month in a different star sign. As such, all the batches have a different energy that interacts with the energy of the user in unique ways. Salt created from water gathered during the new moon contains livelier energy, as the new moon is a phase of new beginnings. Full moon salt, on the other hand, can be used as a closure, to give gratitude to what came on your path, and to leave behind what is not useful anymore. Gathering the water is a spiritual process for Bibi-san, during which she stands directly in contact with the sea deity Kaijin-sama. During the boat ride to the Yabiji reef, Bibi-san prays to Kaijin-sama and sings the ancient Hifumi Norito prayer as a way to honor the gods.

Copyright © Sarah Clay 2024

When I visited Miyakojima, I was interested in how locals and migrants use the sea as inspiration to develop local products that together form the Miyako brand. Some products are small-scale, such as Bibi-san’s Kanashaya salt. Others have grown into big businesses, as the example of 35 Coffee shows. Some products take the bright color of the sea as a starting point, others its symbolism of freedom and purification, still others its spiritual energy. By highlighting the different characteristics of the sea, these products become symbols of the different relationships people have with the sea of Miyako and offer valuable insights into the stories surrounding the natural world of the islands.

References

[1] Rausch, Anthony. 2009. “Capitalizing on Creativity in Rural Areas: National and Local Branding in Japan.” Journal of Rural and Community Development, Vol. 4 No. 2, pp. 65–79.

[2] Website 35 Coffee: https://www.35coffee.com/

[3] See for an in-depth analysis of Okinawan coral gardening: Claus, C. Anne. 2017. “The Social Life of Okinawan Corals.” Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature and Culture, Vol. 11 No. 2, pp. 157-174

[4] Website Kanashaya: https://bibirk.stores.jp/ and https://www.instagram.com/kanashaya/