by Yuki Negi

I’m Yuki Negi, PhD candidate in social anthropology, University of Tokyo. From April 2022 to September 2023, I conducted field research in Ama Town as part of the community building support staff program (chiiki okoshi kyōryokutai) under the Ministry of Internal Affairs. In my contribution to this blog, I would like to briefly present my research project.

https://naimonowanai.town.ama.shimane.jp/amatown

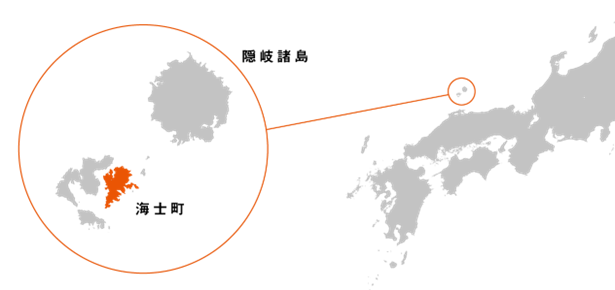

The town of Ama is one of Japan’s most important communities in the field of rural revitalization. However, it is a remote island with difficult geographical conditions, about 2-3 hours away from the mainland by ferry. Some may ask: Is a 2–3 hour drive from the mainland really a big problem? The answer is yes. The ferry from Ama arrives at the port of Shichirui, located on the outskirts of Shimane Prefecture, which has the second smallest population of all 47 prefectures in Japan. To get to another city, you have to take a bus from Shichirui Port to the train station and then take a local train (which runs every hour). In addition, ferry services are often canceled, especially in winter, due to high waves. The journey from Tokyo (Haneda Airport) to Ama usually takes at least 6 to 7 hours and consists of a combination of plane, train, bus and ferry. If you have 6-7 hours to spare, you can travel directly from Haneda Airport to Hawaii or Southeast Asia. Also, unlike many other Japanese islands, there are no famous sightseeing spots in Ama City, and relatively few tourists come to this island.

Copyright © Yuki Negi 2023

Despite these disadvantages, the island has managed to attract young urban migrants and promote industries that take advantage of the natural environment. Today, 20% of the island’s 2,200 inhabitants are urban migrants. The Municipality of Ama has taken the lead in numerous revitalization projects. Most of the people who hold key positions in the municipality are locals who were born and raised on the island. They have all known each other since childhood and maintain a close relationship similar to that of relatives. In this context, such a “closed” kinship group plans and runs various “open” projects to attract new outsiders to the island. When I inquired about the success of rural revitalization upon my arrival on the island, one of the key officials at the town office mentioned that the driving force behind the revitalization efforts was a sense of crisis: the town of Ama, with its history of over 1,000 years, was on the brink of extinction. There was no doubt about that, but it seemed to me that it would be difficult to achieve so much with a sense of crisis. As my research progressed, the question of why this rural island on the national border became a remarkable example of successful rural revitalization came into focus.

Copyright © Yuki Negi 2022

Interestingly, even those involved in the revitalization of Ama cannot explain the reasons for this success. Many of them point to external factors. For example, some attribute it to the geographical remoteness of the island, which attracts young urban migrants while keeping out large commercial capital that could disrupt the social and economic fabric of the community. Some residents also attribute this to sheer luck. Some urban residents who have migrated to Ama, on the other hand, believe that the municipality’s effective use of island resources (people, goods, money, etc.) plays a crucial role in attracting other important resources from outside the region, contributing to the success of local revitalization. A key factor in this success is the ability of the members overseeing the rural revitalization projects to understand the situation on the island and grasp its social and economic structure. The economic structure is unique, as there is only one office per industry on the island to avoid competition on the market. Recently, however, many business owners or craftsmen, e.g. in shipbuilding, are retiring. When they retire, there is a risk that the entire industry on the island will disappear. As residents cannot rely on neighboring towns due to the island’s remoteness, this “closed” society must “open up” and welcome immigrants from the city, especially those with special skills or the desire to work in industries that are threatened with extinction.

Copyright © Yuki Negi 2022

The Municipality of Ama is the main actor trying to attract urban migrants to the island. In such an island society with a limited population, various services need to be facilitated by the town office. Therefore, the town office, where local knowledge and information is gathered, has become a decision-making center for planning rural revitalization projects, taking into account the overall situation of the island. Although this is not unique, the city of Ama has been very successful in attracting people from all over the country. Urban immigrants to Ama Town include individuals with experience working for large companies in urban areas and with knowledge of central government policies and subsidies, which play an important role in augmenting the small rural community’s budget. Because of the presence of these stakeholders, the staff of the municipal office have the opportunity to understand not only how the inside of the island ‘works’, but also how the outside world ‘works’. They skillfully reconcile this naturally (if somewhat unintentionally) acquired local knowledge with the policies of central government and the needs and aspirations of urban migrants. Ultimately, they show that they are able to bring together the interests and aspirations of three different worlds – locals, urban migrants and central government. The city office successfully mobilizes people (both locals and migrants), goods (natural and historical resources of the island) and money (government subsidies, etc.). The increase in resources has created a virtuous cycle in which the town office has been able to mobilize even more people, goods and money. This continuous cycle is a key factor that contributes to Ama being an outstanding example of revitalization. From this point of view, long distance to Tokyo can be an advantage for the revitalization of rural areas in today’s Japan.

Reference: Yamauchi, Michio (2007), Ritōhatsu ikinokuru tame no 10 nen no senryaku, Tōkyō: NHK Press.

Yuki Negi is a PhD candidate in social anthropology at the University of Tokyo.