by Chris McMorran

In January 2022 I was finally able to visit Japan after a two-year gap. Two years of lockdowns, canceled research trips, and courses, meetings, and conferences moved online. Covid-19 disrupted my annual cycle of taking students to Kumamoto each May, visiting Tokyo for short holidays, and visiting family in Kumamoto each New Year’s. My return in January 2022 coincided with 10 months of sabbatical away from NUS and Japan’s reluctant opening to non-Japanese visitors. I could only enter because of my Japanese partner. Japan’s tight regulations on foreign visitors had been polling strongly and boosting PM Kishida’s government, so I expected to find a “closed country” mentality on the streets of Tokyo and Kumamoto, where I split three months.

Instead, I found people as polite and welcoming as ever. Kids playing in the street in my in-laws’ neighbourhood said hello. Staff in shops and restaurants welcomed us enthusiastically. But I did not yet feel comfortable doing interviews or even visiting my usual fieldwork sites, around Kurokawa Onsen (Kumamoto). I feared introducing the coronavirus to the spaces and people I care about so much. I owed a massive debt to those people and did not want to jeopardize my future with them. So I spent my time researching spaces and ideas on the periphery of my main focus: the intersection of tourism and work in rural Japan. And I took advantage of our new shared technological abilities, sharing my latest work in online lectures.

Copyright © Chris McMorran 2022

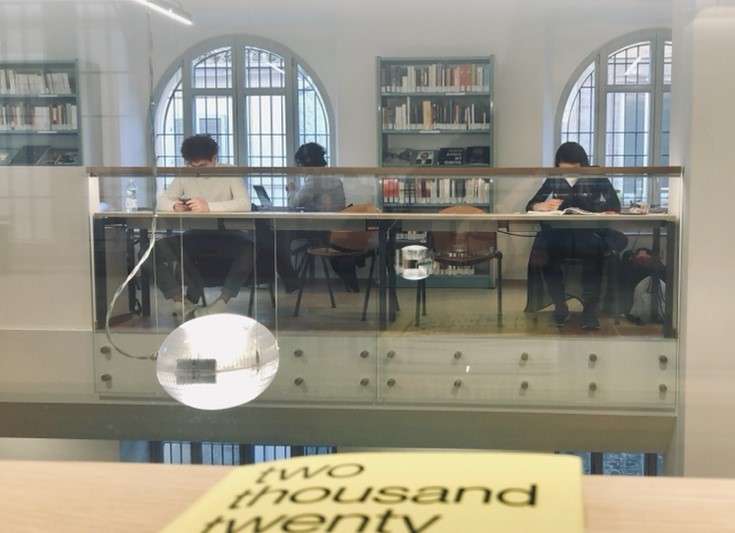

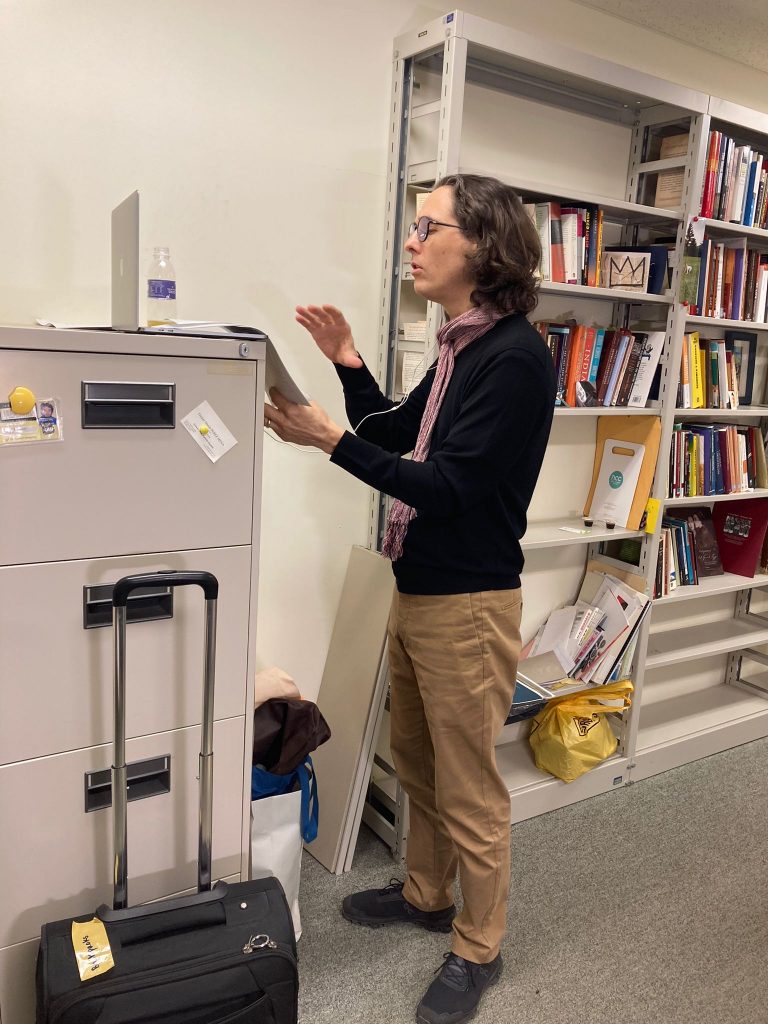

During my three months in Japan I gave lectures for audiences at International Christian University (Tokyo), Kanazawa University and the German Institute for Japanese Studies (DIJ). Under the heightened restrictions from the Omicron wave of January and February 2022, all three talks were moved online. While I felt some disappointment, I was also uplifted by the fact that the online talks could be attended by a truly global audience. My lecture on ryokan for International Christian University could be attended by ICU professors and students, as well as ICU alumni (including one who currently works in a ryokan!), and some of my own students in Singapore. My lecture for Kanazawa University could be attended by super-busy ryokan owners from distant Kurokawa Onsen, and my lecture for the German Institute for Japanese Studies could be attended by researchers based in Europe. These lectures reminded me how broad the global interest is in rural Japan, as well as how inclusive and supportive the network of scholars is.

Copyright © Chris McMorran 2022

While in Tokyo, I was excited to encounter instances of rural Japan reimagined as a new space of combined tourism and work, in the form of the “workation” (work+vacation) Posters in trains and train platforms showed happy individuals sitting in the great outdoors, their laptops strategically open before them. Covid-19 reminded everyone of the inherent risks associated with congested urban spaces. Rural areas have provided a way to escape such risks—and even enjoy one’s work—by working remotely (“telework”). The rural workation moves beyond working from home, which carries its own risks of burnout. Rural Japan—accessible by train—promises the ideal solution. Seeing so many reminders of this reimagination of rural Japan was enough to spur a new research project, one that would have been unlikely had I not returned to Japan.

Copyright © Chris McMorran 2022

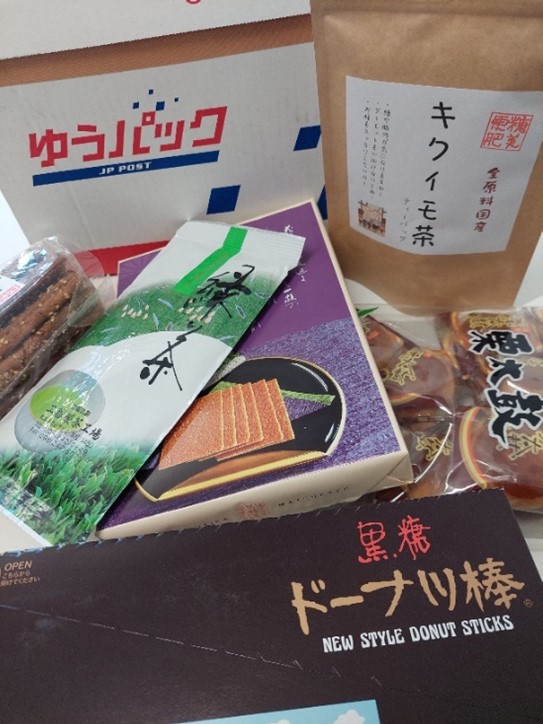

I also visited one of Japan’s oldest onsen, Dōgo Onsen in Ehime, to see how it was weathering the Covid-19 storm. Shopping streets that in normal times would be brimming with shops selling local delicacies and flooded with tourists sat half empty. Some shops were temporarily shuttered. In the shops that were open, staff waited eagerly for the next customer to arrive. The lack of guests meant we could easily bathe in Dōgo’s most famous public baths, without waiting in lines that can normally last hours. It was a reminder that Japan’s tourism industry has a long road to recovery from the coronavirus disruption. My time in Japan was over too quickly, but I was grateful I could reconnect with the country and be stimulated by new potential research avenues.

Chris McMorran is Associate Professor of Japanese Studies at the National University of Singapore. He is a cultural geographer of contemporary Japan who researches the geographies of home across scale, from the body to the nation. His is the author of Ryokan: Mobilizing Hospitality in Rural Japan (2022, University of Hawai’i Press), an intimate study of a Japanese inn, based on twelve months spent scrubbing baths, washing dishes, and making guests feel at home at a hot springs resort. He also co-produces (with NUS students) “Home on the Dot,” a podcast that explores the meaning of home on the little red dot of Singapore.