It’s very hot in Berlin and our team is going on vacation for a few weeks. The blog will be back up on August 9. Thank you for supporting our blog and our activities. Have a wonderful summer.

Cornelia Reiher

It’s very hot in Berlin and our team is going on vacation for a few weeks. The blog will be back up on August 9. Thank you for supporting our blog and our activities. Have a wonderful summer.

Cornelia Reiher

by Cornelia Reiher

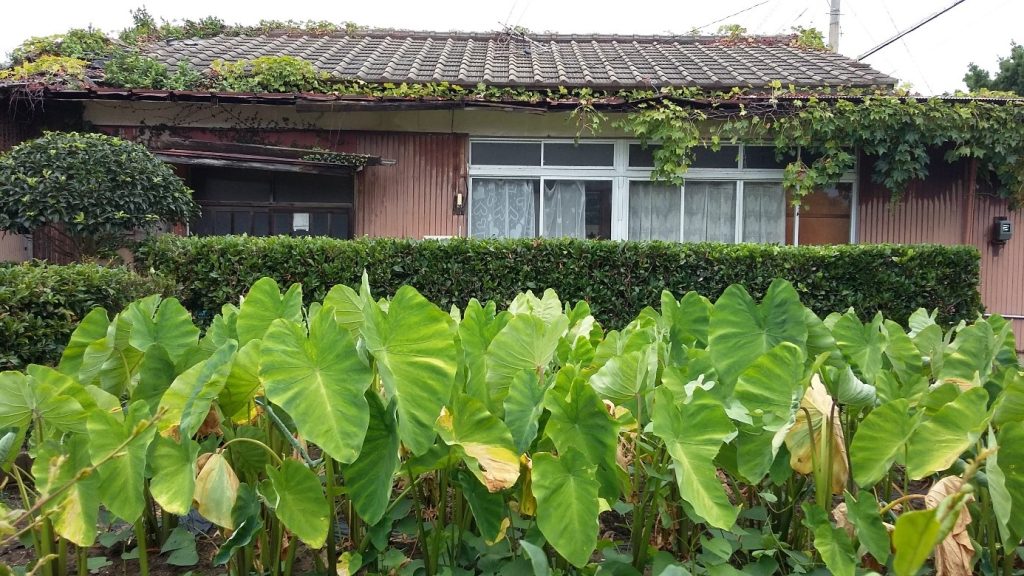

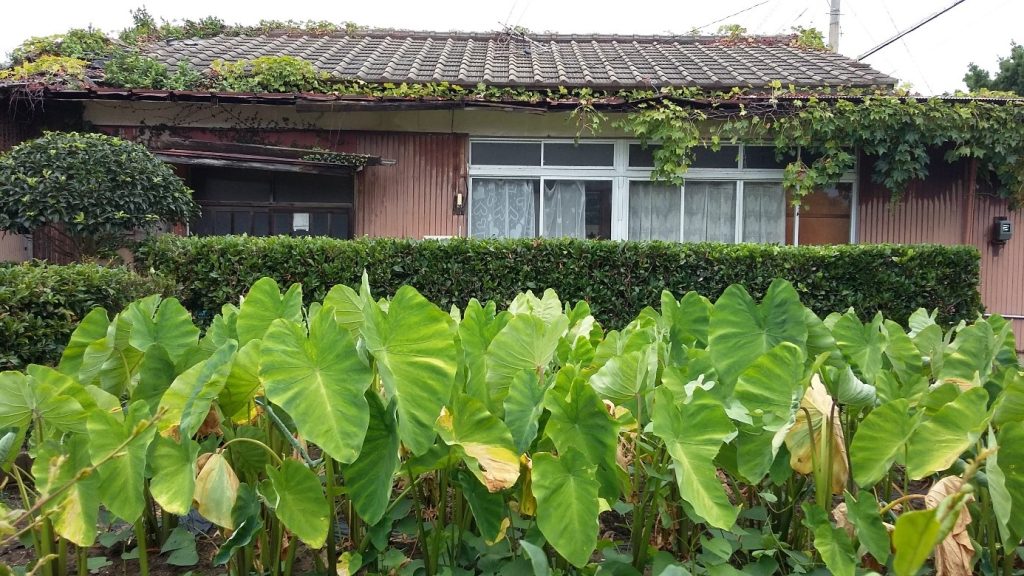

The image of rural Japan as a place where people can live in harmony with nature, raise their children in safety and live in a close-knit social community is conveyed through various media. For many urban-rural migrants, images and stories shared by friends or strangers on social media became one of the many incentives to move to the countryside. And when I had to postpone my fieldwork in Japan during the Covid-19 pandemic, the beautiful images of rice fields, picnics, the mountains and the sea shared on social media provided solace and became the object of my longing at the same time.

However, when scrolling through numerous Instagram accounts, I noticed that the depictions of the countryside often were quite similar in style. Most of them adapted to the changing seasons, showing flowers and trees, children and old people as well as everyday scenes. The profiles of businesses were often a mixture of personal stories about their owners and information about the business itself, blurring the line between private and public profiles. As a newcomer to Instagram, I had assumed that most people took the pictures they post themselves, but when I finally went to Japan, I learned two things: first, the fancy pictures on Instagram are a bit prettier than reality. Second, most of the pictures posted on Instagram were taken by professional photographers and carefully curated.

One of the photographers I met is an urban-rural migrant herself. Her work as a freelance photographer made it possible for her to move to the countryside. The other photographer is a young man from one of the cities where I conducted my field research. For him, photography was a way to stay in his hometown and earn a living. Both photograph for local artists, food stores, hostels or farmers, but also take family portraits for special occasions such as weddings or Shichi-Go-San, a traditional Japanese rite of passage and festival for three- and seven-year-old girls, five-year-olds and sometimes three-year-old boys, which takes place every year on November 15 to celebrate the growth and well-being of children. Many of these images are posted via Instagram, either by their clients or on their own profiles, which also serve to showcase their work and attract new clients.

Yuri (pseudonym) is from Kansai and is in her early 30s. During the pandemic, she was able to work from home and went on “workations.” She visited several places in Japan, including Okinawa, to work. By chance, she met someone who recommended one of my field sites in Kyushu, and she looked at the Instagram profile of an accommodation there. She was fascinated by these pictures, because they gave her a warm feeling and the impression of “being at home.” She immediately contacted the accommodation, visited it twice for a short workation and finally moved there in 2023. Many of her photographs now appear on her hosts’ Instagram profile, she gives lectures on photography and continues to work remotely for a company in Kansai and take freelance photography assignments across Japan.

Takumi (pseudonym) is in his mid-20s and has always lived in his hometown. He decided to attend a university nearby, and when he graduated, he realized that he would like to live and work in his hometown. He has always been interested in photography, but never thought he could earn a living from it. Through contacts with artists, he learned that there are people who live in the countryside but also work for clients in the city and make a living from their art. He got his first commission through a friend, and since then he has been booked by local businesses and families, but also has commissions outside his home prefecture. In addition to his commissioned work, he also photographs the everyday lives of locals and has had several exhibitions showing his work. Many of his photographs are shared on Instagram.

The promotional material provided by rural prefectures and cities aimed at attracting new residents often only reaches a small number of people, but Yuri and Takumi’s pictures on Instagram have a much larger audience. A local government official told me that self-promotion of the experiences of urban-rural migrants in the countryside through social media is much more effective than the videos of local or prefectural governments distributed through YouTube or their official websites. For Yuri, who was attracted to the countryside by images others shared on Instagram, and who now produces and shares such images herself, this is the magic of social media.