by Gina Bresch

In 2019, after finishing school, I decided to go to Japan for a few months to do voluntary service. I ended up in Tokushima City, the capital of the prefecture of the same name on the smallest of Japan’s four main islands, Shikoku. While many of my fellow volunteers, who came through the same agency, were the only ones at their placement, I was lucky enough to become part of a large team of volunteers who worked, ate and lived together. For three months I was part of the NPO “Bizan Daigaku” where I did a lot of hard but rewarding work.

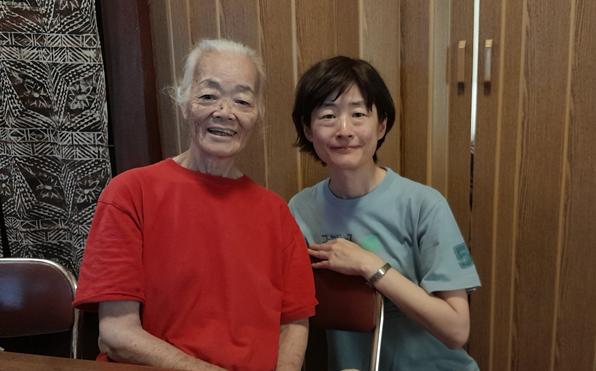

Copyright © Gina Bresch 2019

One of the people I met during that time was a former volunteer who worked at one of the nurseries we sometimes worked at; a Russian woman named Zhanna. After her volunteer work ended, she had traveled a lot in the Tokushima area and liked the tranquility of it more than the big cities in Japan, so she decided to stay. I didn’t see her very often while I was working in Tokushima, but I learned that she had later secured a position as an English teacher. Even after Zhanna left the volunteer program, she remained close to the close-knit community of the Bizan Daigaku organization. We saw each other from time to time, and I was very impressed with her Japanese language skills and admired how she lived in Tokushima, away from her family, and found her own way. I hoped that one day I would be able to come to Japan for a permanent stay like she had.

Copyright © Gina Bresch 2019 and 2023

When I returned to Japan in late 2022, I met Zhanna and found out that she had moved to Kaiyō, a small town on the south coast of Tokushima. She seemed very busy with her work. She told us about her work and what made her move to remote Kaiyō. After living in Tokushima City for a while, Zhanna had begun traveling to Kaiyō on weekends. She saw it as an escape from her busy work life in the city and began to wonder what it would be like to live in this place, which she came to appreciate more and more. At the same time, Zhanna had started taking surfing lessons in Tokushima City, and since Kaiyō is known to have the biggest waves in the prefecture, she thought it would help her improve her surfing skills if she moved there. When I talked to her, she even called it “Surfers’ Mekka.

Copyright © Zhanna V. 2022 and 2023

Zhanna lives in Kaiyō, but works in a town called Minami, which is 40 minutes away by car. She works in the Regional Revitalization Division of the Tokushima Southern Prefectural Office, which includes Kaiyō City, Minami City, Anan City, and others. Of these, I was only familiar with Anan City because one of the nurseries where I volunteered was located there. As you might expect, these are very remote areas that are struggling with depopulation. Zhanna is responsible for the English versions of the prefectures’ social media sites, as well as photographing “the best views and local traditions,” all with the goal of revitalizing the region. Through her work, she hopes to help promote some of the region’s specialties and its appeal to attract more (foreign) tourists to visit the southern, rural part of Tokushima Prefecture. It also involves a lot of translating and interpreting Japanese promotional material into English, such as brochures. Finally, her SNS work consists of appearing on the prefectural government’s YouTube channel, showcasing various places and activities in the area.

Copyright © Zhanna V. 2022 and 2023

On the other hand, she participates in tourism fairs and conventions and speaks at the annual “Silver Daigakko” event, which is designed to help recruit new volunteer guides in Tokushima City. Her presence as a foreigner helps the cause of revitalization by adding another perspective to these rural areas that can be attractive to both Japanese and foreign visitors. Zhanna calls Tokushima a “treasure chest for exploration” and would like to share this place with many people so that they can experience a different side of Japan. As for her hopes for the future, she hopes that the infrastructure of southern Tokushima will be developed and that her work will help the area become more popular to attract new tourists. That way, the money they earn from tourism could help local people improve their lives and live more comfortably. In particular, she wants to promote the various unique festivals that take place between August and November, such as the Anan Danjiri Kenka Matsuri. I wish her and her work all the best for the future and hope to see her soon, perhaps when visiting Kaiyō myself.

Gina Bresch is a student in the BA program in Japanese Studies at the Freie Universität Berlin.