By Galina Khoikhina

In August 2020, I went to Hida Furukawa, located in Gifu Prefecture. I was an exchange student in Japan and travelled to this small city as a part of my term paper project about the relationship between anime pilgrimage and rural revitalization. Anime pilgrimage (anime seichi junrei) is a type of tourism based on people visiting places that appear in an anime. Hida Furukawa, became famous as a destination for anime tourism in 2016, just after the release of Makoto Shinkai’s animated film “Your Name (Kimi no na wa)”.

The animated film “Your Name” tells the story of Mitsuha, a girl from the countryside and Taki, a boy from Tokyo. Although they are strangers, they begin to switch bodies from time to time, and through this experience learn more about each other’s life. According to the plot, Mitsuha lives in the small town of Itomori. It is a fictional town, but many locations could be found in Hida Furukawa and its surroundings.

The goal of my project was to find out how the release of the animated film “Your Name” affected the tourism industry in Hida Furukawa. To answer my research question, I went to Hida Furukawa and visited tourist information centers, kumihimo workshops and the city library. I also talked with residents.

First thing I found out was that the tourist information centers offer a map for anime pilgrims. It shows the locations of the places, which appeared in the film, and provides general information about the city.

Copyright © Galina Khoikhina 2020

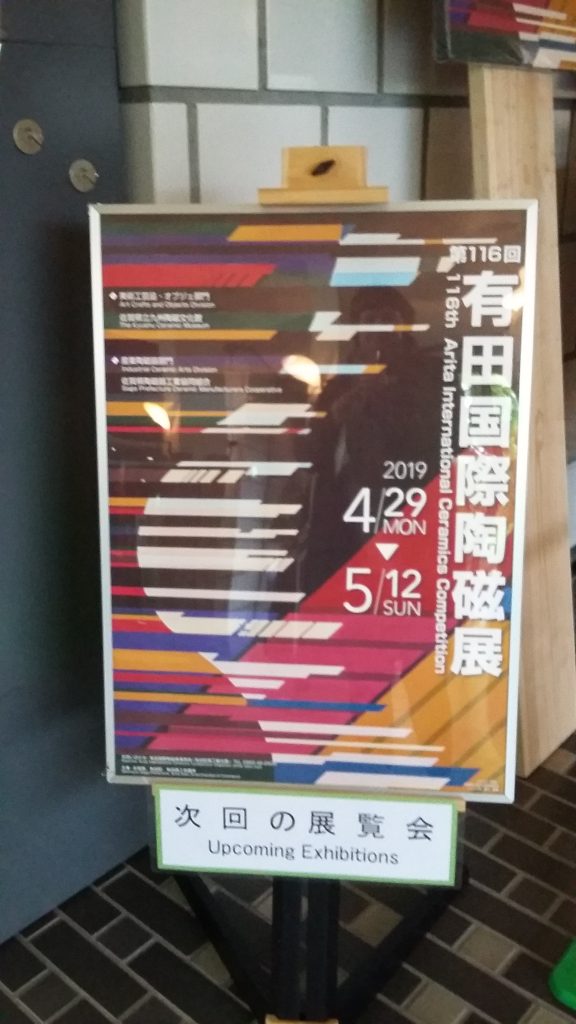

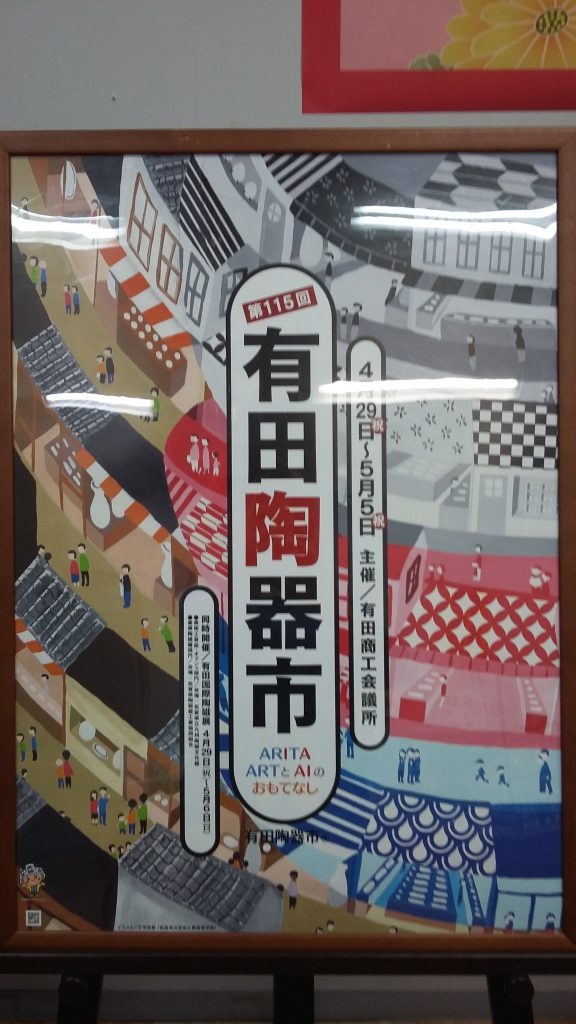

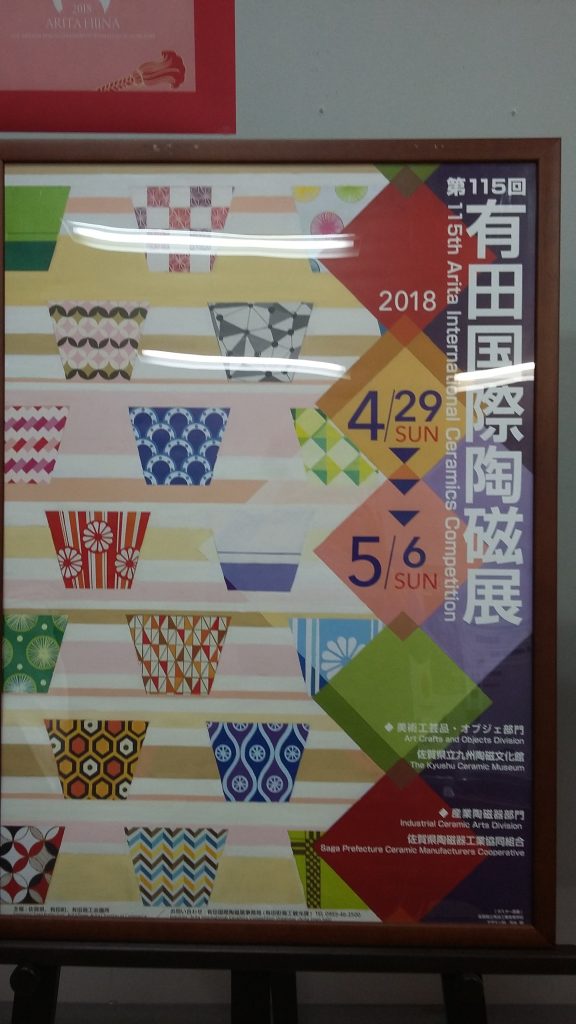

The release of the anime film “Your name” also influenced the souvenirs sold to tourists. In addition to selling official anime goods, souvenir shops also sell local products, which are adjusted specially for anime pilgrims. For example, local sake is sold in the same bottles that appear in the anime.

Copyright © Galina Khoikhina 2020

Furthermore, kumihimo workshops were organized for anime tourists. Kumihimo is the Japanese art of making cords, and it plays an important role in the anime “Your Name”. These workshops allow residents to interact with tourists.

Copyright © Galina Khoikhina 2020

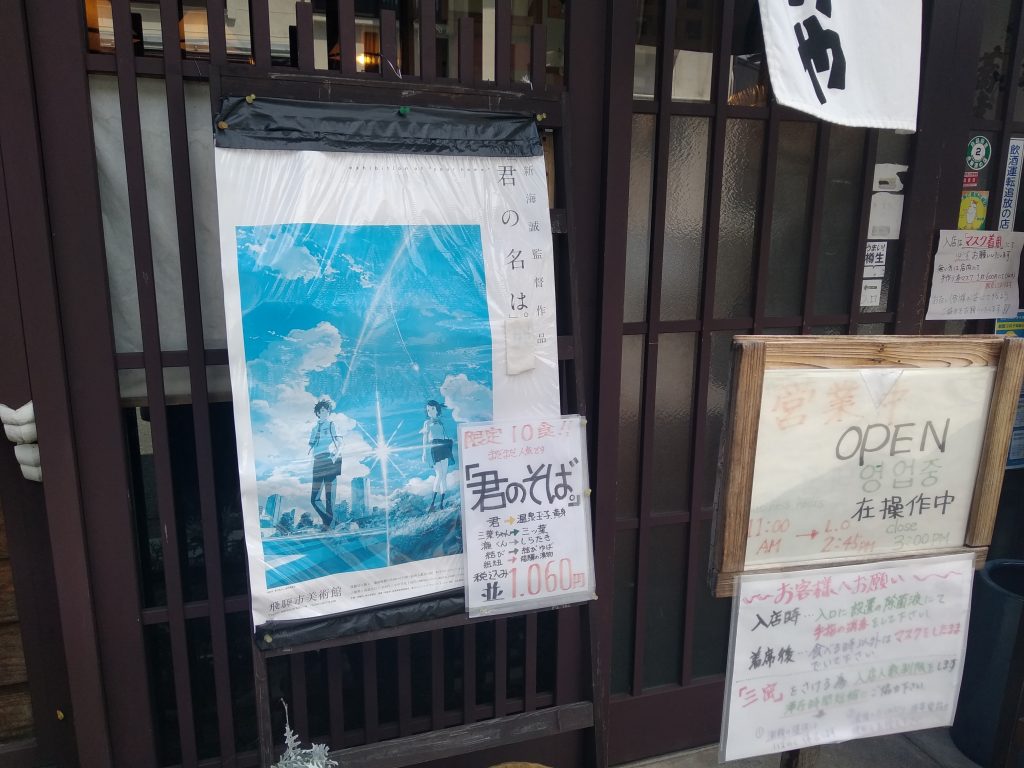

Some restaurants have also changed their marketing campaigns to attract anime pilgrims. Eateries offer discounts to tourists who came to Hida Furukawa to visit “the sacred sites”.

Copyright © Galina Khoikhina 2020

Another interesting location is the city library. Since it played a big part in the anime, tourists began to visit it a lot. Some of them disturbed the readers, so the staff even had to introduce rules for anime pilgrims. However, the librarians are very friendly to properly behaved anime pilgrims. They created a special “Your Name” corner, where visitors can make photos and leave feedback.

To conclude, Hida Furukawa is an example of how anime content can be successfully integrated into existing tourism strategies and provide citizens working in this industry with a high level of interaction with anime pilgrims.

*Galina Khoikhina is a BA student in Freie Universität Berlin’s Japanese Studies program. She is currently working on her BA thesis about tourism in rural Japan.