by Julia Olsson

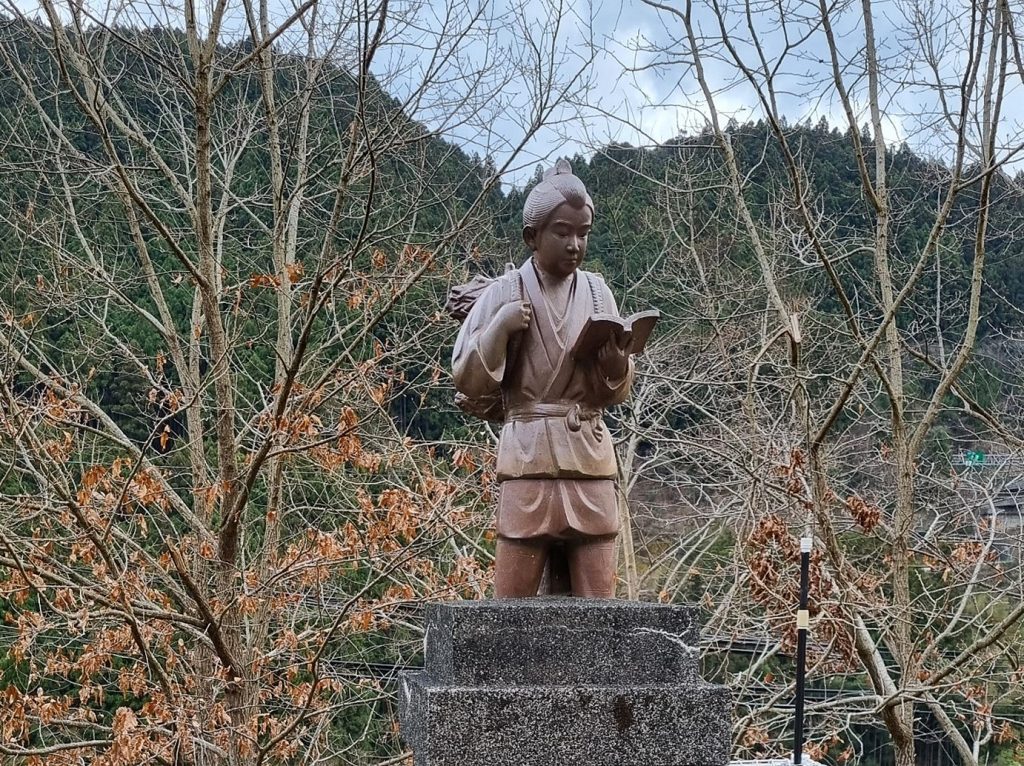

One night during fieldwork in Kochi prefecture, I found myself the only guest at a hostel in the mountains of Otoyo. It is not the easiest place to get to unless you have a car, and even then, my teacher and I drove a bit back and forth before we came to the right drop-off place. I was left at the side of the road with a steep stone stair between me and the pink, wooden building I had found online earlier that week. It is called Midori no tokeidai, named after its green roofed clocktower. However, until 2006, it was known under another name: Kawaguchi Elementary School.

Copyright © Julia Olsson 2023

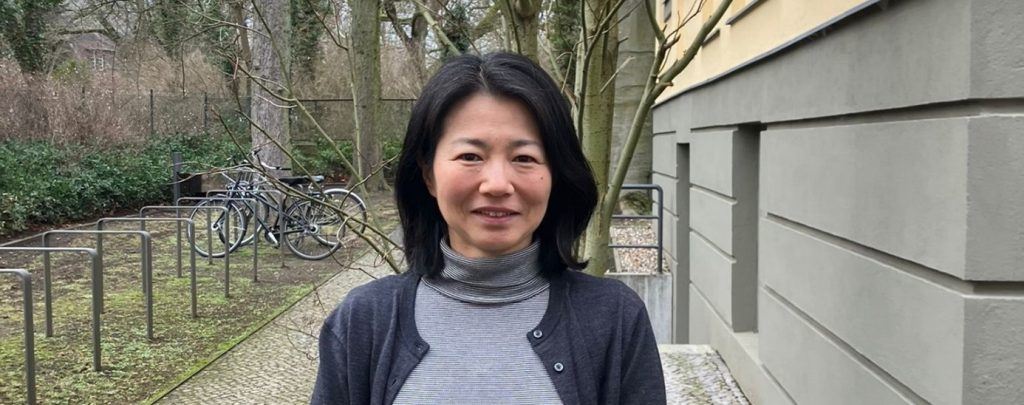

I have visited several Japanese elementary schools as part of international events as an exchange student and I am familiar with the design from movies, TV shows, and manga, but have never attended one myself. It was therefore a strangely familiar feeling to walk the empty halls of this hostel, looking in at the classrooms turned sleeping halls for visiting school classes. Today, the hostel is a place to stay at school excursions or for visiting sport teams. Most things are kept as they were when the building still housed students. Even the blackboards are left up. However, in contrast to a real school, you are encouraged to doodle. Midori no tokeidai was abandoned about 17 years prior to my stay in 2023. In the same year, it was taken over and renovated by I-turn migrants Yumi (or principal Yumi as she is affectively titled on the hostel website) and her husband Masaki. With games such as zōkingake rēsu or cleaning rag race, where people race against each other in the hallways while cleaning the floor with a large rag, the hostel invokes school nostalgia for visitors. “You are allowed to do the things that you would get scolded for at school, so it’s like a dream come true,” a guest remarks on a YouTube clip on the hostel homepage.

Copyright © Julia Olsson 2023

Closed schools are a typical sight in ageing and depopulated rural Japan. In the town of Otoyo alone, this elementary school is one of twelve that have closed in the last 25 years, not to mention middle and high schools. Schools are a symbol for children, the next generation and thus for the future itself. When they are closed, they are a stark reminder to residents of their uncertain future. When a new purpose is found for schools or other public buildings it is possible to reimagine the future as something new.

Copyright © Julia Olsson 2023

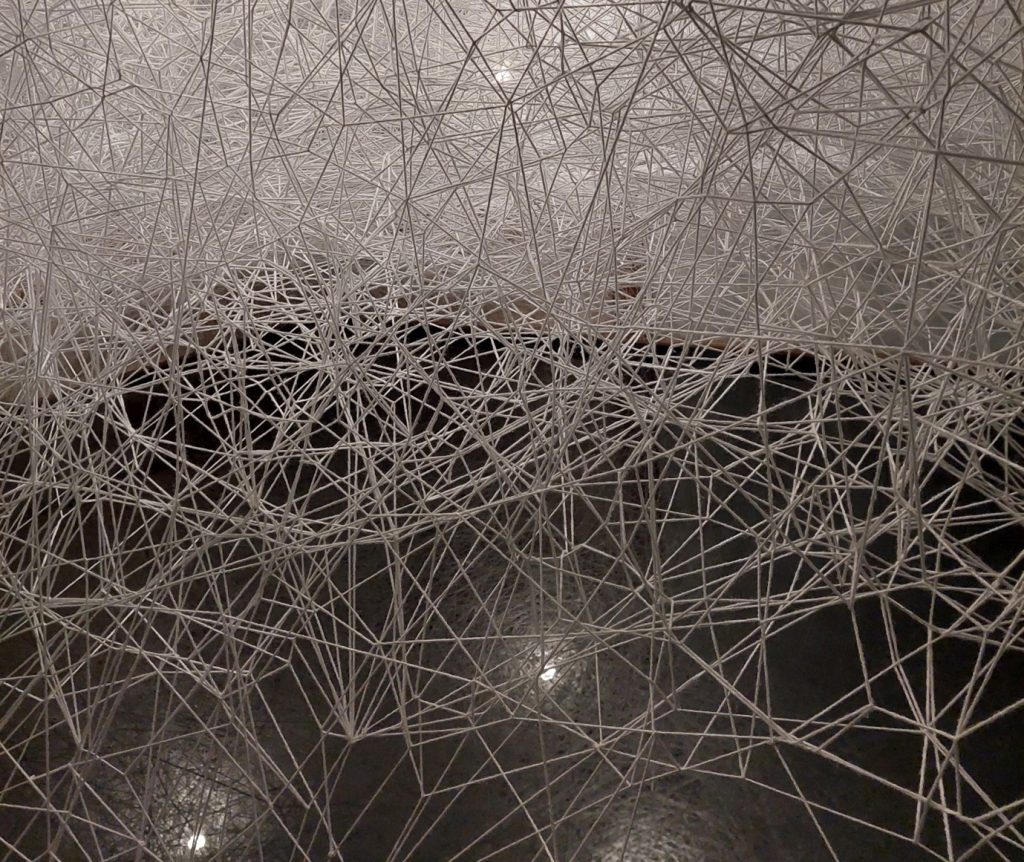

As seen in this blog, media (both traditional and social), and in scholarship, repurposing abandoned buildings in rural Japan has gained much attention in recent years. In addition to DIY projects for urban migrants, vacant houses are increasingly renovated and turned into guest houses, cafés, and art installations (Platz 2024). As telecommuting has been mentioned as a possible solution to depopulation of settlements, a need for office space has also emerged (Matsushita 2022). I saw several schools, kominka and an old factory in Kōchi being used for this purpose. As shown in a workshop in Yamagata (Takahashi et al. 2014), there are many more options for the use of vacant houses, ranging from community centers to libraries to demolition for the construction of golf courses. While community-led initiatives have proven to be positive in both finding creative solutions and fostering community spirit, many emphasize the need for leadership, especially in revitalization projects that focus on repopulation. It takes a village, but it also takes a driving force, which scholars refer to as a “star migrant” (Yamagishi and Doering 2025). This represents both a possibility and a vulnerability for communities striving to repopulate.

Copyright © Julia Olsson 2023

It is important to remember that there were eleven other elementary schools in Otoyo that have not fared as well as the hostel. While the successful cases are uplifting, I must admit that I am not convinced they are as significant. The undeniable truth is that not every place can become the next big tourism destination and even fewer are likely to experience significant repopulation. I wonder how we can think about those places, and what they mean for the future of rural Japan. The tension, between celebrating success stories and recognizing the realities of decline, is something I struggle with. While the story of Midori no tokeidai and its owners is a rare case of someone choosing to build a life in a depopulated village, most places will not be so fortunate. If we focus only on the positive cases, we risk overlooking the many places and people left behind. At the same time, looking at these exceptions offers a glimpse into what’s possible, even if only for a few.

As I was alone that night in the hostel, I stayed in what used to be the main office, just off the entrance and next to the large communal kitchen. In the evening, principal Yumi joined me for a meal and a couple of drinks. Her husband was in the hospital, so it was just the two of us. She told me about their move from Osaka to Otoyo, drawn by the town’s excellent river rafting conditions, and about her involvement in an NPO focused on attracting urban migrants. It is just one of her many social engagements. For Japanese urbanites looking to relocate and for Otoyo Yumi might indeed be a “star migrant”. Midori no tokeidai is an inspiring place, and I look forward to another visit next time I am in the area.

References:

Matsushita, K. (2022). How the Japanese workcation embraces digital nomadic work style employees. World Leisure Journal, 65(2), 218–235.

Platz, A. (2024). From social issue to art site and beyond – reassessing rural akiya kominka. Contemporary Japan, 36(1), 41–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/18692729.2024.2314331

Takahashi, R., Ishibashi, K., Sugiyama, R., & Aiba, S. (2014). ‘Akiya katsuyō machizukuri keikaku’ sakusei e no shimin sanka shuhō no kaihatsu [Development of a method for citizen participation in the creation of a “vacant house utilization community development plan”], Nihon kenchiku gakkai gijitsu hōkokushū, 20(44), p.273-278.

Yamagishi, D. & Doering, A. (2025). Dressing up the place: Urban lifestyle mobilities and the production of “fashionable” tourism destinations in rural Japan. Tourism Management, 106, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2024.104995

Julia Olsson is a first year PhD student at the Centre for East and South-East Asian Studies, Lund University in Sweden. Her main research interests include rural depopulation, rural-urban dynamics, vacancy, and post-growth futures.