by Ngo Tu Thanh (Frank Tu)

The venues of policy formulation are a labyrinth of actors, negotiations, calculations, and conflicting interests. Rural revitalization policies are no exception. Interested in finding out how rural revitalization policies are made, and moreover, how policy actors operate behind the scenes, I knew I would need visit Nagatachō – Japan’s political center.

On 08 June 2022, I was very fortunate to meet with a veteran who has been navigating politics in Nagatachō for more than 20 years. He is an ideal research participant whom I really wished to interview: after finishing his PhD in Urban Planning at an Ivy League institution, he became a Chief Policy Secretary (kokkai giin seisaku tantō hisho) for several members of the House of Representatives (Shūgiin) and the House of Councilors (Sangiin). In the past, he once ran for the House of Representatives and has considered running for mayor. After losing his parliamentary bid, he decided to work in academia and advocacy. He is now a researcher at a think tank for the LDP, a public policy consultant, and a professor in urban planning. Having had experience in both the Diet, advocacy, and academia, he did not hesitate to speak his mind freely and was able to get down to the nitty-gritty of politics.

Copyright © Ngo Tu Thanh 2022

I arrived in Nagatachō, where my research participant’s advocacy organization is located. There, I found myself standing in front of a big four-story building. Located within one kilometer from our meeting place are some of the most crucial institutions where rural policies (among others) are made: the National Diet (Kokkai), the Cabinet Office (Naikakufu), the headquarters of the Liberal Democratic Party (Jiyūminshutō), the headquarters of the National Governors’ Association (Zenkoku Chijikai), the headquarters of the National Mayors Association (Zenkoku Shichōkai), the National Association of Chairmen of Prefectural Assemblies (Zenkoku Todōfuken Gikai Gichōkai) and the National Association of the Chairpersons of Town and Village Assemblies (Zenkoku Chōsongikai Gichōkai). The presence of police officers and guards everywhere further evoked my anxiety. After a few seconds of hesitation, I took a deep breath and entered the building.

An employee opened the door and guided me to the couch where my research participant was sitting. After greeting each other, I followed him to a spacious conference room on the top floor, where I conducted the interview. On our way I saw officers in black suits rushing around, people whispering softly to each other in different corners, and some cautiously making phone calls by the window. My interview partner shared with me that his organization accommodates many former national and local politicians, ambassadors and governmental officials. Advocacy organizations like this are part of the intriguingly complicated policymaking process, which involves the national government, the national Diet, local governments, local assemblies, and private organizations.

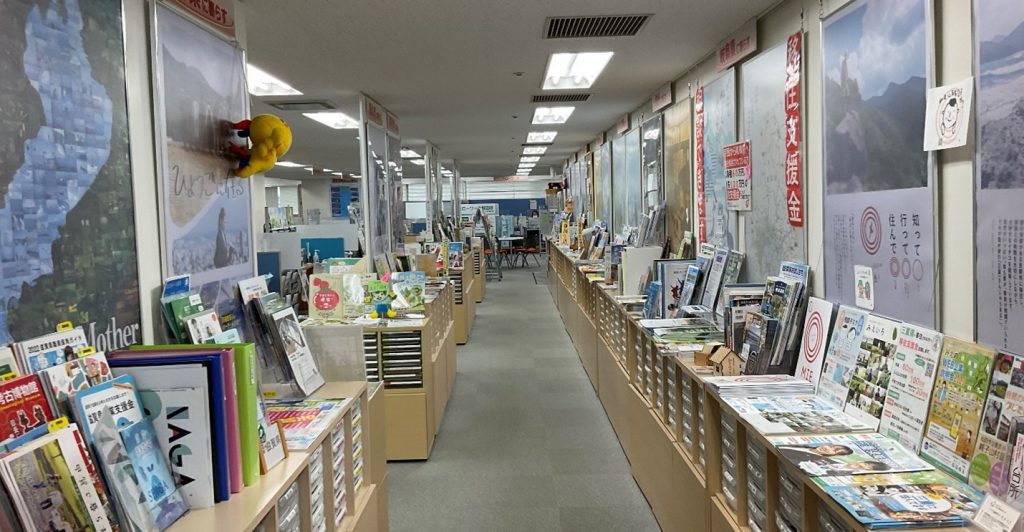

Local representation can also be found in Tokyo

Copyright ©Ngo Tu Thanh 2022

According to my research participant, first, revitalization policies are drafted by relevant ministries (i.e., Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communication; Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry; Ministry of Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism). Then, the policies are compiled by the Headquarters for Regional Revitalization, which is located in the Cabinet Office. The Headquarters for Regional Revitalization is where officials from relevant ministries meet and discuss their responsibilities and jurisdiction.

At the same time, the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), also has its partisan counterparts of the Cabinet Office and the Headquarters for Regional Revitalization, namely the Policy Research Council (Seimu Chōsakai) and the Headquarters for Overcoming Population Decline and Regional Revitalization (Chihō Sōsei Jikō Tōgō Honbu). Politicians belonging to this LDP’s organ will voice their desires to influence the plans proposed by the Cabinet Office and relevant ministries. They will push for what is beneficial to their constituencies such as IT promotion, or attracting young people to the countryside.

Besides, associations that represent prefectures and municipalities also actively lobby for policies in their favor. The National Governors’ Association, the Headquarters of the National Mayors Association, the National Association of Chairmen of Prefectural Assemblies, and the National Association of the Chairpersons of Town and Village Assemblies. These associations present proposals (teigensho) that favor their localities at large.

Copyright © Ngo Tu Thanh 2022

Finally, there are also advocacy organizations that work for the interests of private businesses. For instance, the Japan Business Federation (Keidanren) or my research participant’s organization often lobby for clients who want national and/or local governments to adopt favorable policies. Hence, in addition to lobbying activities in Nagatachō, his organization also reaches out to local governments all over Japan. In particular, such advocacy organizations often formulate their own proposals and meet with relevant politicians. My interview partner asserted that while not always successful, private advocacy organizations do have great sway in policymaking.

After all these behind-the-scenes constant interactions, negotiations, lobbying and pressuring between myriads of actors, the official rural revitalization policies are decided on. As complicated as it sounds, this interview has intrigued me greatly and prompted me to proceed to the next stage of my research – the prefectural and municipal levels, which I am now very much looking forward to.