Our team will take a break over the holidays. The blog will be back on January 13.

Thank you for following and supporting our activities.

Happy holidays.

Seasons decoration in a fish tank in Sasebo

Copyright © Cornelia Reiher 2004

Our team will take a break over the holidays. The blog will be back on January 13.

Thank you for following and supporting our activities.

Happy holidays.

Seasons decoration in a fish tank in Sasebo

Copyright © Cornelia Reiher 2004

by Cecilia Luzi

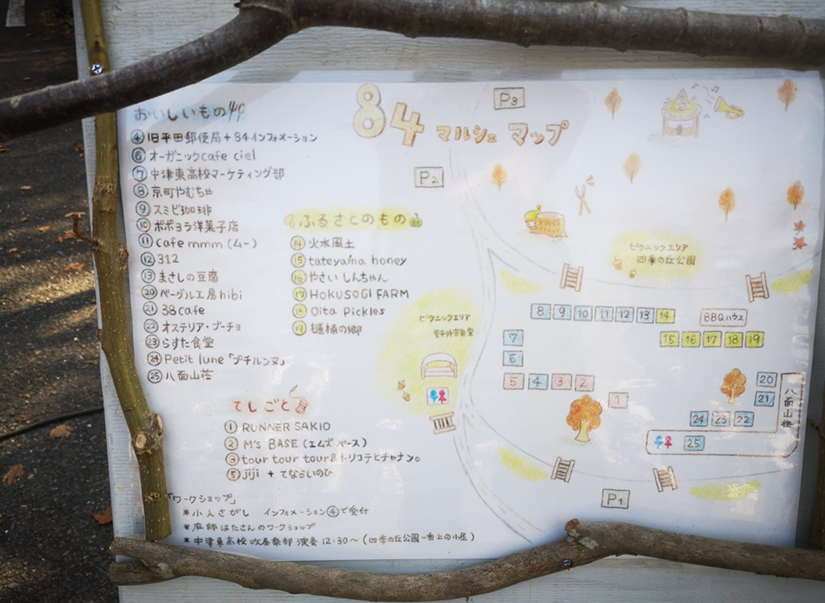

Before I started my field research in Japan this October, I read about many local markets in Kyushu on social media. Many of them are organized by migrants who have moved from the city to the countryside. When several people I had met in Buzen told me about the 84 Marché in Nakatsu, Oita Prefecture, I was very excited to finally visit a market myself. When we left our house around noon on a sunny November day to go to the market, it was 20 degrees. The market was held in a park, and after climbing a winding road between maple trees with bright red autumn leaves, we saw a clearing with 25 stalls at the bottom of the hill. The stalls offered various products, from clothing and beauty products to coffee, honey and lunch boxes.

A map of 84 Marché

Copyright © Cecilia Luzi 2022

I spotted M-san waiting for a coffee and waving at me. She was one of the people who had invited me because she wanted me to meet one of her friends, a craftsman who builds stone walls for terraced fields and also speaks impeccable Italian. He was a left back on a Serie D soccer team in central Italy and has lived in Viterbo for four years. We strolled through the stalls sampling honey, coffee and roasted sweet potatoes. After half an hour, I had already run out of the business cards I had brought with me, expecting to be able to talk to a certain number of people about my project – which I had obviously underestimated, because there were so many urban-rural migrants at the market. And many of them had transnational migration histories, like M-san’s friend or the girl who runs an Italian restaurant in Nakatsu and lived in Rimini for three years to learn Italian cooking. We bought coffee from a man who had moved to Nakatsu from Tokushima, and cannellé from another man who was originally from Fukuoka, had lived in various cities in Japan, and then moved to Koge in Fukuoka Prefecture a few years ago. We also talked to a girl who had just moved here from Tōkyō to train as a farmer, and another man who had moved from Nagasaki to Yabakei in Oita Prefecture to open a small vegetarian restaurant. We also met a young man who had just graduated from chiiki okoshi kyōryokutai (COKT) in Sanko, Oita Prefecture, and was organizing the market. He currently lives in a share house with three other urban-rural migrants and wants to start an eco-village.

View of the market square

Copyright © Cecilia Luzi 2022

As we stood on the porch where the sweet potatoes were being grilled, amid the hot, sweet smoke rising from the coals, I asked M-san how long these markets have been around. “I would say the first ones started about ten years ago. The name ‘marché’ (marushee) is French, isn’t it? French always sounds cooler to the Japanese. There are Christmas markets now, but I’ve never been to those. Other markets in this area that have always existed are mainly fruit and vegetable markets where local farmers sell their produce.” I told her I was amazed at the number of migrants I met today, and asked her if it was normal to see so many of them at these events. “I would say it depends on who is organizing it. This event is organized by the guys from Chiiki okoshi kyoryokutai from Sanko, and I think that’s why there are so many migrants here. It’s kind of their thing.” It is their second market after a first market was held in the spring. “This year they finished the program [COKT] and I don’t know if they will organize more markets. Maybe someone else will take over, or maybe they’ll just stop.”

One of the stalls selling coffee

Copyright © Cecilia Luzi 2022

During my online research, I had already noticed that many markets took place only once or twice and then stopped. This might be due to the fact that those who organize them have a precarious job or do it in their spare time. Moreover, these markets seem to be the initiative of one or two people who are interested in bringing people together as long as they have the time to do so. In some cases, when they are no longer able to organize these events, others step in. In other cases, the markets simply cease to exist. But M-san also mentioned farmers’ markets, and the day after my visit to the 84 Marché, I had the opportunity to visit one. It was organized by local government officials and integrated into the local infrastructure, also with the help of local government employees. I have the impression that this facilitates the institutionalization of such events. In my next post, I will write more about the farmers’ market and reflect on the similarities and differences between these two different types of markets.

by Lynn Ng

“I lived three years in the countryside of Hokkaido!” This is often one of the first things I tell people. For the longest time, I prided myself a rural-experienced urbanite, for I had experienced the ups and downs of the rural life. So, as I made my way to a small village in mountainous Fukushima, I was thrilled to once again put on my rural rose-tinted glasses. Aboard one of four daily buses that travel into this village, I imagined the rolling hills, rice paddies, snow-capped mountains, clear rivers that awaited me at the destination.

What the road into the village was like, with the abundant nature I imagined myself to be immersed in upon arrival.

Copyright © Lynn Ng 2022

After an hour of romanticizing rural Fukushima in my head, I arrived at my accommodation – a former shophouse now used to host volunteers and interns of community revitalization projects. This house sits between a steep brown hill and a small rocky stream. Unruly grass grew everywhere and an ambient radiation measuring device hides itself nearby, behind tall grasses and rusted fences. Outside the dark, empty house, I shouted: “Konnichiwa!” Silence. I wondered if I had arrived too early, that the staff had not been expecting me, yet. Or had I arrived too late and the staff already went home? I attempted to check my communication history for a number to call but alas, the signal was bad. I began to realize how inexplicably ill-prepared I was.

The air radiation monitoring device nearby reads 0.189 microSieverts/h – more than double of Berlin’s ambient dose rate (0.073 microSieverts/h) [1].

Copyright © Lynn Ng 2022

After a brief moment of internal panic, an old lady came running from out of nowhere across the street (where the steep hills were) towards me. She shouted to me something I could not understand and knocked on the windows of the house. I worried how badly my Japanese comprehension had withered away after just a year. The staff popped out of the office quickly. How she had heard the two knocks on the glass but not my incessant konnichiwas, I wondered. I turned to thank the old lady but she was no longer there. “There are no locks here, anywhere here,” the staff member said. I asked about Wi-Fi. “None,” she said, and then added, “there is a convenience store about fifteen minutes on foot, but it closes in about thirty minutes.” I put down my bags and prepared to run to the store.

Within mere minutes of setting things down, however, a small earthquake struck the village. The public radio announced that everyone in unstable housing structures should go to the nearest evacuation center. I wondered if this house was structurally viable. I wondered where the closest evacuation center was. I attempted to google. There was no internet. Abandoning all thoughts of heading out at all, I crawled onto a chair and allowed myself time to reflect on these realities of my first day, and of my upcoming week here: a week of unlockable doors, no groceries in the vicinity, and no Wi-Fi. On this first day in rural Fukushima, urbanite-Lynn experienced culture shock. I sat by the kitchen table shivering in my Tokyo-appropriate clothes. My stomach growled. I stared gloomily at the portable humidifier I bought just before boarding the bus. Why hadn’t I bought food or hot packs instead? As I had decided to leave all of the day’s problems to tomorrow, the old lady from before knocked on my door with a bowl of pumpkin stew in hand. I wondered how she gained access and remembered that there were no locks in this whole place.

The heartwarmingly delicious bowl of pumpkin stew.

Copyright © Lynn Ng 2022

I wrote these reflections while chewing on bits of soft pumpkin in the dim kitchen. I pondered upon this culture shock of the vast disparity between my imagination and the realities of living in this village. The ambient radiation numbers displayed on the tucked-away measuring device had easily become a non-concern. I wondered how other rural migrants here felt on their first day – had they also met this mysterious old lady? Or had they spent the day walking around finding phone signals? How did their imaginations match up with reality? On this first night, as I headed off to bed, I tripped on the uneven tatami, pinched my fingers twice on the wooden doors, tucked my valuables under my pillow and slept to the sounds of the stream flowing softly outside while a hundred questions raced through my mind.

[1] Ministry of Environment Japan. (2019). Ta chiiki no kūkan senryō-ritsu to no hikaku [Comparison of ambient radiation to other areas]. Available at:

https://www.env.go.jp/chemi/rhm/portal/digest/dwelling/detail_003.html