The summer term ends in Berlin and we will go on a vacation. We will be back with more posts about rural Japan on August 19. Have a great summer!

Copyright © Cornelia Reiher 2015

The summer term ends in Berlin and we will go on a vacation. We will be back with more posts about rural Japan on August 19. Have a great summer!

by Johannes Wilhelm

It is the end of February 2020. From my wooden house at the southern foot of the inner volcanic cone of the huge caldera of Aso (Kumamoto Prefecture), I am heading for Tokyo, where I will give a lecture on the “Cowboys of Aso”. Before departure, I check the latest mails. The organizer mails that in view of the beginning pandemic and in agreement with the Japanese authorities all events at the institute have to be cancelled at short notice. Well! I stoically took note of the decision, but on the plane the sense of my outward and return flight seemed quite absurd. After a few days, I was back at the volcano, while at the first shopping in the only supermarket of Minamiaso, surprisingly, neither official trash bags, nor toilet paper was to be found: everything bought empty. I asked my relatives and friends in Tokyo and elsewhere if this was also the case there, but they were all surprised, because everything was still available. The following week, however, some of them came forward and told me that a run on toilet paper had now also begun in the other major cities of Japan. Then – about two weeks after Aso – I read in the foreign media that, in addition to toilet paper, noodles were also becoming scarce. At that time I remembered the lyrics of a song by the German band Tocotronic about the new strangeness, which opened up to me like the discovery of a new semiotic continent … https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZweXZqoV7nc&ab_channel=OMhA

Minamiaso thus became a trendsetter in terms of social phenomena in the pandemic, at least as far as toilet paper was concerned. And the trash bag shortage soon died down, too. Later, other oddities in the countryside came to light, such as alcohol dealers who out of the blue marketed their whiskey or shochū as disinfectants, or some greenies trying to sell overpriced masks of dubious origin at moon prices, but I want to focus on other things in this text.

Many people with an affinity for Japan are probably aware that the Aso region is one of the main tourist attractions on Kyūshū Island. It occupies a correspondingly prominent role in local economic life, although in my opinion the main pillars of the economy are the welfare sector (keyword: aging) in addition to agricultural production. An important fact is that the working life of many people in Aso consists of several parts. For example, many rely on their land holdings to pursue a primary activity such as cattle raising or rice cultivation, while also pursuing a few side jobs, such as cleaning public baths in the evenings or producing handicrafts such as embroidery, woodwork or pottery offered at michi no eki or other outlets. Full-time jobs are only those in the administration of the city hall or government offices and schools as well as full-time positions in production facilities in the industry. The structure of the tourism sector is similarly diverse. The domestic tourists, but mainly those visiting from abroad, usually only see the hotels, restaurants or inns, i.e. the superficial manifestations of the industry with their many employees, but behind them there is a whole range of sub-enterprises, such as dry cleaners for bed linen.

Just a couple of weeks before the so-called “Golden Week”, it was decided that all public baths and the onsen thermal baths, which are extremely popular among tourists, would be closed for an indefinite period. Lodgings and restaurants were also ordered by local authorities to take a rest period. When I went to the nearest dry cleaning business in May to prepare my winter clothes for proper storage over the humid summer, I was told that from now on the business would only run on Saturdays every fortnight and only a quarter of the staff – mainly full-time employees – would still be present, as there was no demand in the light of the closed lodges.

… to be continued …

Johannes Wilhelm is an independent researcher and is affiliated with Vienna University. His main studies focus on the relationship between nature and society. His interests include fisheries, pastures in mountainous regions, and rural areas as much as general phenomena in society such as radicalism, migration and social vulnerability.

by Lynn Ng

As a child, whenever I complained about Singapore’s horrible heat and humidity, my parents would show me pictures of snowscapes. “Mind over matter,” they always said. I never believed in the “science” behind my parents’ actions, because those pictures only ever made me feel envious of people who do not live in the tropics and never any cooler than before. Yet, this week as I sweat through yet another T-shirt in Berlin, I decided to look up the photographs of my time in snowy Hokkaido for comfort in this hot time. Along with this decision came a strong nostalgia for this region I once called home.

In 2015, I transplanted myself from tropical sunny Singapore to a rural town that buries itself in over 200cm of snow every winter. I enjoyed the snow – the softness and refreshing cold that comes with it. But more than snow, I relished the quiet rurality. Rural Japan, and especially rural Hokkaido, is beautiful. Like most urbanites in rural Japan, I arrived with rose-tinted glasses. Everything in the countryside was wonderful – the untouched nature, the friendly people, the countless cheap hotsprings… the list goes on.

Over the years, I would notice how tinted these glasses were for rural Hokkaido is of course not without its problems. There were moments when I wanted to catch a movie in the theaters only to realize the nearest showing was in a city two hours away. The train there would arrive at either 8 a.m. or 4 p.m., or would be cancelled in case of snow. Such trivialities aside, I saw also the underutilized theme parks and landmarks built with private funds during the bubble or supported by government funds for rural revitalization. Many local residents complained to me that these projects were a waste of money since no one goes there, and yet these parks were some of my favorite places to visit for the additional quietness.

Let us also not forget that rural Hokkaido also has plenty of snow, and with it comes the art of yukikaki (snow shoveling) that is the pride of Hokkaidoians – the Dosanko. Much like household chores, yukikaki is a mundane activity many Dosankos do especially in the wee hours of the morning. Dosankos have repeatedly told me that yukikaki was a means of boosting work ethic and instilling discipline in children. I once met a family who chose to start a farm in Hokkaido because they thought it would instill the best work ethic in their children – something urban cities or other rural places in Japan could not offer because of the extra activity of yukikaki. For three years, I simply found yukikaki a chore.

Perhaps I never had good discipline to begin with, nor particularly strong work ethics by Japanese standards. Or was it because I never did yukikaki and thus have no discipline? Which came first? And for this, every winter I was reminded of being the “outsider.”

Indeed, rural Japan and rural Hokkaido carries with it its own set of problems. As I reminisce about the goods and bads of my three years in there, I can only proudly say that I regretted nothing of it. Perhaps my glasses are still rose-tinted till today, or perhaps there is something truly enticing about rural Hokkaido that one cannot simply let go of despite all of its problems.

by Shilla Lee

Recent studies on regional revitalization movements in Japan have explored various local initiatives to mobilize the urban population to rural areas (Klien 2020; Manzenreiter et al. 2020). While they provide us with rich contexts, the discussions seem to revolve around an essentially anthropocentric account of regional sustainability. I want to bring attention to my rough ideas about a new perspective to scrutinize the social implication of regional revitalization movements in Japan: to broaden our discussions beyond the human-human domain by exploring problems of depopulation within the wider panorama of human-wild animal (pestilence) relations.

There have been growing cases of wildlife damage in depopulating regions across the globe. Let me briefly mention an article published by The Guardian in January 2021 (Flyn 2021). It talks about how declining fertility rates have led to serious social problems in wealthy countries like Germany and Japan. However, rather than focusing on issues of birth rate per se, the discussion develops into changing human-animal relations in scarcely populated regions. Highlighting a case of akiya (empty house) in Japan, the article directs our attention to how abandoned farms and gardens are reclaimed by wild animals due to an absence of human existence and how we should be more serious about the contrasting state of shrinking human population and prospering wildlife.

In this context, I suggest that we expand our notion of regional revitalization to non-human beings and question whether regional ‘re’vitalization also implies a power ‘re’distribution between humans and wild animals. When discussing rural social problems such as depopulation, aging, and declining local economy, they are dealt with as issues of human society, precluding social and physical spaces shared (or fought over) with non-human beings. We need to think about whether various strategies that attempt to pull in (attract) the human population such as migrants, tourists, and foreign workers to rural regions also pushes away wild animals that are wandering around once human-dominated habitats. As recent studies on human-wild animal (pestilence) relations show (Enari 2021; Enari and Tsunoda 2017; Tsunoda and Enari 2020), remote village communities lack human forces or community spirits to protect crops from wild animal damage and tensions rising from such conflicts lead to increasing practices of wildlife pestilence to control their population.

The prosperity of wild animals beyond human control “can appear a threatening development that points to the retrenchment of human society rather than a benign revival of nature” (Knight 2003:236). Moreover, at a municipal level, increasing conflicts with wild animals not only create economic damages but also undesirable images of rural livelihood, thereby, affecting key strategies of regional revitalization policies that focus on domestic tourism and urban-rural migration. As Knight points out “the impact of the wildlife pest is not confined to the material damage it causes to individual farmers and foresters but extends to its negative symbolism vis-a-vis the community as a whole” (2003:237). As much as rural areas are relying on incoming tourists and migrants for their economic and social sustainability, any source of negative images poses challenges. In this sense, regional revitalization is not only a matter of increasing the human population but also of adjusting human-wildlife relations.

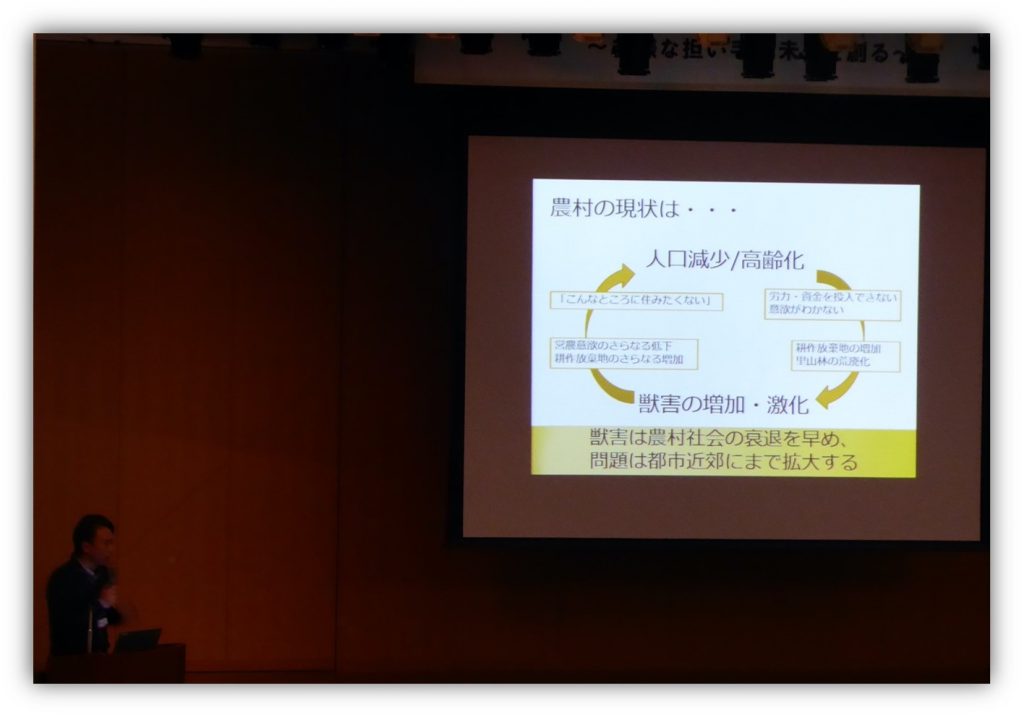

Let me briefly illustrate Wildlife Damage Forum that was held in Tamba Sasayama during my fieldwork in 2018-2019. One of the main actors that dealt with problems concerning wildlife damage in the region was an NPO named Satomon. According to what is written on their official webpage, their key concern is the “wildlife pestilence problem” (jyūgai mondai) by monkeys, deers and wild boars that threatens a Satoyama lifestyle. They argue that wildlife damage takes away the joys of harvesting by referring to young people who move to rural areas and then give up their dreams of living a peaceful country life: “Young migrants who are fascinated by the countryside and relocated to work on farms also said, ‘I cannot work the fields in such a place’ and are giving up their dreams and leaving the villages” (nōson ni miryoku o kanji, ijūshite shinki shūnō shita wakamono mo,” konna tokoro de nōgyō wa dekinai” to yume o akiramete mura o satteiku). It is in this context that Satomon suggests what they call the “wildlife pestilence measure” (jyūgai taisaku) and organizes Wildlife Damage Forum as one of their key initiatives.

An event for the year 2019 was held on a cold day in December in a shimin sentā (citizen center) in Tamba Sasayama. Following an opening speech by the mayor, representatives of various local organizations addressed their ideas to tackle the growing damage by wild animals. A group of social scientists first pitched a behavioral observation of wild boars in the region to examine what kind of damage prevention mechanisms would work. The next speaker demonstrated how the aging community and wild animal damage should be thought of together. Lastly, a group of local middle school students presented a school club activity that produces coin purses from leathers of wild deers. What I found interesting was how they all began with an emphasis on the importance of living with wild animals, however, sought co-existence through curtailing the population growth of the latter. For instance, the business idea presented by the middle school students to rethink human-wild animal conflicts as a way to make profits from the latter was premised on the legitimacy of wildlife hunting and other measures to eradicate the overpopulation of deers. Similar ideas were found in local restaurants that promoted wild boar meats as a local delicacy and a wild meat processing business started by a recent urban-rural migrant. Wild animal damage was being cope by residents by reframing it as a source of economic prosperities and attractive elements of the region.

References

Enari, Hiroto. 2021. “Human-Macaque Conflicts in Shrinking Communities: Recent Achievements and Challenges in Problem Solving in Modern Japan.” Mammal Study 46 (2): 115–30.

Enari, Hiroto, and Hiroshi Tsunoda. 2017. “Emerging Wildlife Issues in an Age of Large-Scale Human Depopulation—Introduction.” Wildlife and Human Society 5 (1): 1–3.

Flyn, Cal. 2021. “As Birth Rates Fall, Animals Prowl in Our Abandoned ‘Ghost Villages.’” The Guardian, January 24, 2021.

Klien, Susanne. 2020. Urban Migrants in Rural Japan: Between Agency and Anomie in a Post-Growth Society. State University of New York Press Albany.

Knight, John. 2003. Waiting for Wolves in Japan: An Anthropological Study of People-Wildlife Relations. Oxford University Press.

Manzenreiter, Wolfram, Ralph Lützeler, and Sebastian Polak-Rottman. 2020. Japan’s New Ruralities: Coping with Decline in the Periphery. Routledge.

Tsunoda, Hiroshi, and Hiroto Enari. 2020. “A Strategy for Wildlife Management in Depopulating Rural Areas of Japan.” Conservation Biology 34 (4): 819–28.

Shilla Lee is a PhD candidate at Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology in Halle, Germany. Her research focuses on the notion of rurality and creativity in regional revitalization practices and the cooperative activities of traditional craftsmen in Japan.

by Ngo Tu Thanh (Frank Tu)

The venues of policy formulation are a labyrinth of actors, negotiations, calculations, and conflicting interests. Rural revitalization policies are no exception. Interested in finding out how rural revitalization policies are made, and moreover, how policy actors operate behind the scenes, I knew I would need visit Nagatachō – Japan’s political center.

On 08 June 2022, I was very fortunate to meet with a veteran who has been navigating politics in Nagatachō for more than 20 years. He is an ideal research participant whom I really wished to interview: after finishing his PhD in Urban Planning at an Ivy League institution, he became a Chief Policy Secretary (kokkai giin seisaku tantō hisho) for several members of the House of Representatives (Shūgiin) and the House of Councilors (Sangiin). In the past, he once ran for the House of Representatives and has considered running for mayor. After losing his parliamentary bid, he decided to work in academia and advocacy. He is now a researcher at a think tank for the LDP, a public policy consultant, and a professor in urban planning. Having had experience in both the Diet, advocacy, and academia, he did not hesitate to speak his mind freely and was able to get down to the nitty-gritty of politics.

I arrived in Nagatachō, where my research participant’s advocacy organization is located. There, I found myself standing in front of a big four-story building. Located within one kilometer from our meeting place are some of the most crucial institutions where rural policies (among others) are made: the National Diet (Kokkai), the Cabinet Office (Naikakufu), the headquarters of the Liberal Democratic Party (Jiyūminshutō), the headquarters of the National Governors’ Association (Zenkoku Chijikai), the headquarters of the National Mayors Association (Zenkoku Shichōkai), the National Association of Chairmen of Prefectural Assemblies (Zenkoku Todōfuken Gikai Gichōkai) and the National Association of the Chairpersons of Town and Village Assemblies (Zenkoku Chōsongikai Gichōkai). The presence of police officers and guards everywhere further evoked my anxiety. After a few seconds of hesitation, I took a deep breath and entered the building.

An employee opened the door and guided me to the couch where my research participant was sitting. After greeting each other, I followed him to a spacious conference room on the top floor, where I conducted the interview. On our way I saw officers in black suits rushing around, people whispering softly to each other in different corners, and some cautiously making phone calls by the window. My interview partner shared with me that his organization accommodates many former national and local politicians, ambassadors and governmental officials. Advocacy organizations like this are part of the intriguingly complicated policymaking process, which involves the national government, the national Diet, local governments, local assemblies, and private organizations.

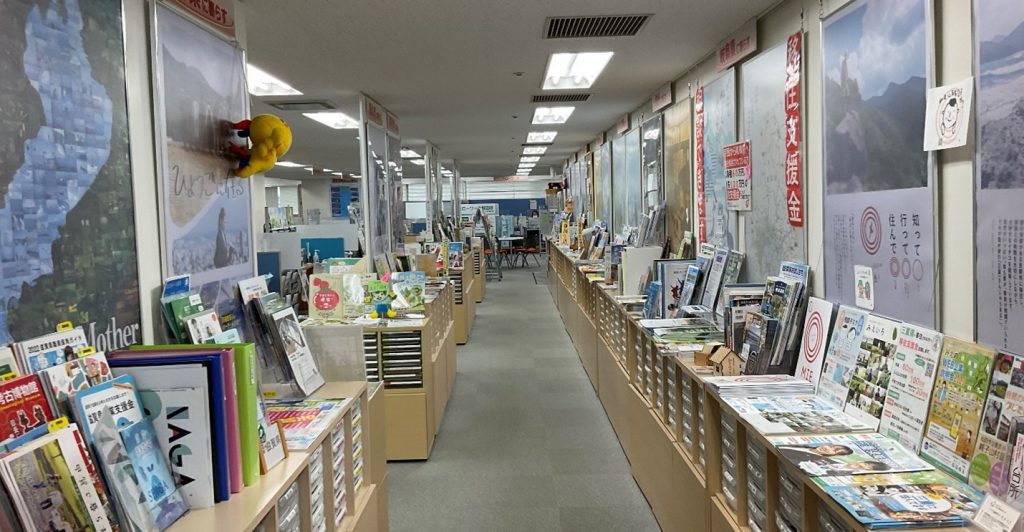

Local representation can also be found in Tokyo

Copyright ©Ngo Tu Thanh 2022

According to my research participant, first, revitalization policies are drafted by relevant ministries (i.e., Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communication; Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry; Ministry of Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism). Then, the policies are compiled by the Headquarters for Regional Revitalization, which is located in the Cabinet Office. The Headquarters for Regional Revitalization is where officials from relevant ministries meet and discuss their responsibilities and jurisdiction.

At the same time, the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), also has its partisan counterparts of the Cabinet Office and the Headquarters for Regional Revitalization, namely the Policy Research Council (Seimu Chōsakai) and the Headquarters for Overcoming Population Decline and Regional Revitalization (Chihō Sōsei Jikō Tōgō Honbu). Politicians belonging to this LDP’s organ will voice their desires to influence the plans proposed by the Cabinet Office and relevant ministries. They will push for what is beneficial to their constituencies such as IT promotion, or attracting young people to the countryside.

Besides, associations that represent prefectures and municipalities also actively lobby for policies in their favor. The National Governors’ Association, the Headquarters of the National Mayors Association, the National Association of Chairmen of Prefectural Assemblies, and the National Association of the Chairpersons of Town and Village Assemblies. These associations present proposals (teigensho) that favor their localities at large.

Finally, there are also advocacy organizations that work for the interests of private businesses. For instance, the Japan Business Federation (Keidanren) or my research participant’s organization often lobby for clients who want national and/or local governments to adopt favorable policies. Hence, in addition to lobbying activities in Nagatachō, his organization also reaches out to local governments all over Japan. In particular, such advocacy organizations often formulate their own proposals and meet with relevant politicians. My interview partner asserted that while not always successful, private advocacy organizations do have great sway in policymaking.

After all these behind-the-scenes constant interactions, negotiations, lobbying and pressuring between myriads of actors, the official rural revitalization policies are decided on. As complicated as it sounds, this interview has intrigued me greatly and prompted me to proceed to the next stage of my research – the prefectural and municipal levels, which I am now very much looking forward to.

by Cornelia Reiher

Although I could not go to Japan during the Covid-19 pandemic, I came across and learned about rural Japan in unexpected places. When interviewing Midori (pseudonym), a Japanese chef in Berlin for my project on Berlin’s Japanese foodscapes in summer 2021, she introduced herself as Yusuhara Future Design Ambassador (Yusuhara mirai taishi) and gave me a name card with her name and that title on one side (in English) and some basic information about Yusuhara, a small town in Kochi Prefecture in Shikoku on the back (in Japanese). The name card also stated that with this meishi I could receive a 500 JPY discount when entering the hot springs in Yusuhara. I was surprised about this coincidence and also because I had never heard about Future Design Ambassadors.

Left: Midori, one of Yusuhara’s Future Design Ambassadors in Berlin

Copyright © Cornelia Reiher 2022

Right: Nishima Jinja in Yusuhara is one of Midori’s favorite spots

Copyright © Midori 2022

Midori was born in Kochi in Shikoku, but she has never lived in Yusuhara. Her best friend is from Yusuhara and the first time she went there was for her friend’s grandmother’s funeral. She was surprised and moved by the warm welcome and cordial atmosphere at the funeral that was unlike all the other funerals she had attended to this point. Everybody was nice to her although she did not know anyone except her friend. After this event she regularly returned to Yusuhara and got to know many people. She made many friends and was impressed by their kindness and the beautiful nature. After she had moved to Germany, she brought friends from abroad to Yusuhara whenever she returned to Shikoku.

Midori displays information brochures about Yusuhara in the Japanese restaurant she works at in Berlin and distributes meibutsu from Yusuhara to people interested in Japan

Copyright © Cornelia Reiher 2022

As Yusuhara’s slogan is “Seikai to tsunagarou!” (connect with the world) and because Midori had become acquainted with the mayor, in 2020, the townhall contacted her and asked her if she wanted to promote Yusuhara in Germany as a mirai taishi. She submitted her CV and received the meishi she gave me when we first met. And she is not the only mirai taishi. Many volunteers like her were asked to spread information about Yusuhara in other parts of the world. The activities are not defined and due to the Corona-19 pandemic Midori mainly distributed tourism and information brochures to people interested in Japan. Once a year, Yusuhara’s town hall sends cookies and other small presents, mainly food products, she gives to people interested in Yusuhara. In the future, Midori plans onsite events to introduce Yusuhara to a larger audience and wants to invite young people from Yusuhara to Berlin.

I received a tourist map in English promoting Yusuhara as “the town above the clouds”, postcards with pictures of beautiful scenery and a Japanese brochure for people interested in moving to Yusuhara. This brochure was strikingly similar to others I have picked up in other places in Japan. It showed pictures of happy children and families enjoying outdoor activities in beautiful scenery, images of the four seasons and local festivals. It also introduced U and I turn migrants and their experiences. The brochure also presents support schemes for child rearing, finding housing and for the renovation of vacant houses (akiya). It also promotes the medical infrastructure in Yusuhara. The target groups for in-migration into Yusuhara, according to the information material I received, are young people and families with children. Migrants under the age of 40 receive financial support for building or renovating a house and families receive all sorts of discounts for education, housing and child care.

Yusuhara is known as a rather successful example of rural revitalization and as particularly environmentally friendly [1]. The famous architect Kuma Kengo designed several buildings in the town, including the library, a welfare center, a hotel, a gallery and the town hall. Thus, Yusuhara has become a destination for fans of architecture [2] and an eco-model city that launched a low carbon initiative, uses renewable energies like wind and biomass and stresses the coexistence with the surrounding forests [3]. This does not only become visible in Kuma Kengo’s wood architecture, but also in the promotion of forest therapy. Several therapy roads promise relaxing effects of forests in Yusuhara for “people living in the modern times”. This has not only attracted tourists and newcomers, but also shows how small rural communities in Japan can be innovative, sustainable and transnational, all at the same time.

References

[1]

Beyer, Vicky L. (2020), Yusuhara: the eco-friendly traditional mountain town, https://jigsaw-japan.com/2020/02/12/yusuhara-the-eco-friendly-traditional-mountain-town/

[2]

Presser, Brandon (2019), This Japanese Town Has Become a Secret Destination for Architecture Buffs, https://www.cntraveler.com/story/this-japanese-town-has-become-a-secret-destination-for-architecture-buffs

[3]

Yusuhara-chō (2022), Kankyō e no torikumi, http://www.town.yusuhara.kochi.jp/town/

by Maritchu Durand

This year in early May, I took a few days off to visit my family in the south-western French countryside and to enjoy the mild and sunny spring. The region’s nickname “the French Toscana” suits the hilly region with small fields of cereal grain or sunflowers well. A few kettle farms spread over the country and small quiet villages with old stone farmhouses, vegetable gardens and the obligatory area for playing pétanque [1] on the village square right next to the small church and a one-room city hall can be found here and there.

Traditionally an agrarian region, most of the farmers are now either close to retirement or do other jobs on the side. They are usually part of a cooperative that sell their crops to bigger firms. However, amid this rather industrial production chain, there are exceptions that started in the 1968’s back-to-the-land movement that seek alternative and more direct ways to connect farmers and consumers.

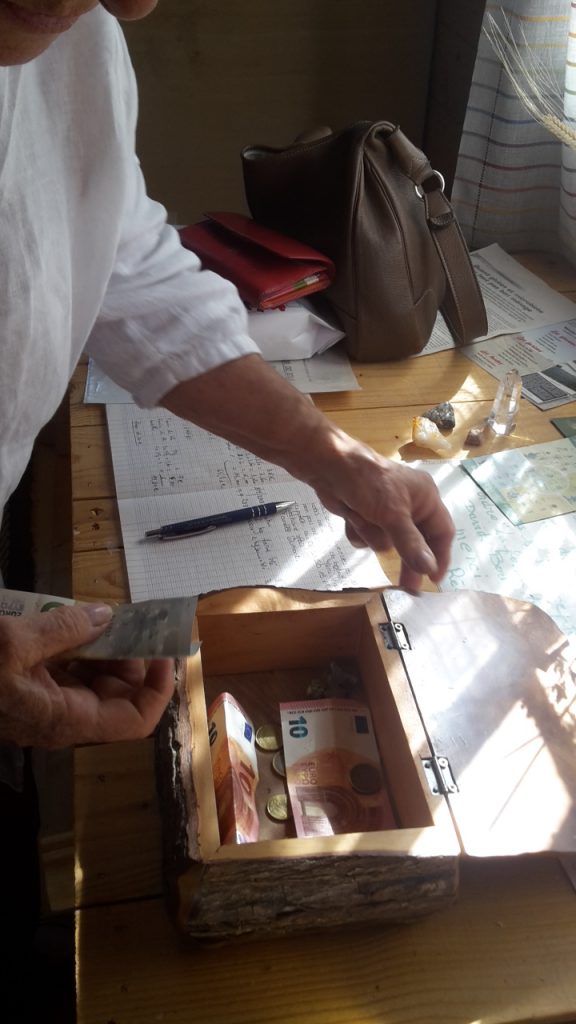

One such example is the “Poppy Cabin”, a 30 minutes walk from my grandparents’ village. You can enter the bright red cabin from the small countryside road. Although it is in the courtyard of the farmer who manages it, I never meet anyone. Depending on the season, there are different products for sale, all either certified organic or from the so-called “reasoned agriculture” [2]. The farmer sells mostly cereals and pulses in various forms that he produces: dried lentils and chick peas, rye, spelt, wheat or chick pea flour are almost always available. You can also find honey, sunflower oil, onions, garlic or different root vegetables and a local artisan’s hand-made soap.

Once you have filled your basked, you simply write down your name a well as what you bought and how much you paid on the ledger and put the money in the small wooden box on the table. It is a system based on trust and a strong network: there are no signs on the cabin, it merely works by word of mouth. At the same time, by writing down your name, you lose the anonymity usually linked to consumption.

While browsing through the home-made packages of flour, I was strongly reminded of a very similar system in Japan: the mujin hanbai stalls – mujin stands for “without anyone”, and hanbai for “sale”. When I travelled through the Japanese countryside, I frequently encountered small stalls on the side of the road. Usually very rustic and simple shelves that are filled with produce packaged by locals: mikan, umeboshi, daikon and many other local and seasonal products for an astonishingly cheap price. I was very surprised when I first saw an umeboshi stall. It was so cheap that I thought I was mistaken, I therefore hesitated, afraid of paying the wrong price, and I passed by without buying anything. I regret it until this day.

Although different in its interpretation, the core of both systems is the same in Japan and in France. It is a system based on trust within a small community. First, the seller trusts the consumer to pay the right price, take only what he or she paid for and leave the place unharmed. In return, the customer trusts the producer with the quality and safety of the product. Since it is locally grown in a place the customer sees and values, he or she might find a meaning in buying the produce beyond the mere fact of consuming. This is at least what my grandmother told me when she first brought me to the Poppy Cabin: she wanted to support the local farmer, a young passionate return migrant who had taken up his grandfather’s farm. She praised the quality and unique taste of the products she regularly bought and appreciated the ‘no-fuss’ aspect of the system.

The Poppy Cabin and the mujin hanbai stalls share the principles of mutual trust, attachment to a community, appreciation of the soil and its produce and connecting producers and consumers. All are aspects that are often associated with an ideal countryside. In the interviews and articles by urban-rural migrants I encountered while working on this project, they mention these aspects very often as the very reasons for moving to the countryside. Although the Poppy Cabin and the mujin hanbai stalls are only small and rare realizations of those principles, they might prove that the ideal images prospective migrants express about the countryside might be more than mere imagination.

[1] Pétanque or boules is a popular game in France where players through heavy metal balls towards a smaller wooden target ball. It is played on village squares and enjoys great popularity in southern France.

[2] The French Ministry of Agriculture defines reasoned agriculture (l’agriculture raisonnée) as a type of farm management that aims at reinforcing the positive impacts of agricultural practices on the environment and at reducing their negative effects. Closely linked to organic farming, it does not however require any certification.

by Sebastian Polak-Rottmann

I visited the Aso region in Kumamoto Prefecture several times between 2018 and 2020 to conduct research for my PhD project. I talked to local people who engage in local activities about their views on happiness. Here, I will concentrate on different patterns of participation that I encountered during my research. I observed several ways in which people try to influence their local communities. Most people emphasised that they like to make others happy or share the local natural landscape with others and therefore collectively make significant effort to preserve it. However, when arriving in Aso for the first time in 2018, I came across an exceptional case of local activism aimed at preserving the local scenery. A local livestock farmer decided to build a cattle barn close to a train station in Aso-city. While regional organisations and the regional administration initially supported the project financially, local inhabitants opposed the location of the facility, as they feared a deterioration of the hamlet’s quality of life. I met two representatives of the so-called Movement for the Relocation of the Construction Site of the Big Cattle Barn (Ōgata gyūsha kensetsuchi no iten o motomeru kai) that used a number of strategies of political participation to channel residents’ voices. The movement consisted of a number of local people and former bureaucrats who collected signatures from about 8,000 people for a petition, contacted local as well as prefectural politicians, and even organised a demonstration on a cold winter’s day [1].

The demonstration was a quite unusual event for the rural Aso region where many people usually use informal ways to influence local politics, as Mariko, a woman in her 60s emphasises: “I usually go directly to the mayor, if I have a proposal. The mayor went to the same school as my brother, so I just go to him and say: ‘This is what I want to do’. He even visited us once and I think he recognises my face by now and so things will be easier next time”. Protesting against a cattle barn is also a controversial matter in another sense: Aso is famous for its akaushi-beef, which is served in a number of restaurants for tourists around the whole region. Cows are an integral part of the distinctive grassland (sōgen) of the Aso caldera and some of the farmers engage in the local grassland associations (bokuya kumiai) and the traditional burning of the grass (noyaki) in February and March.

Due to the importance of livestock farming in Aso, the protest challenging the local farming industry needed to be done in a careful manner: The name of the movement emphasises that the protesters do not oppose the construction of a cattle barn per se but rather wish for another site for the building. It is not surprising that those, who criticise the whole funding and construction process in a more encompassing way, soon left the movement, which did not seek open confrontation with local policy makers. In the end, the cattle barn was built and the movement did not reach its goal of relocating the barn. Also, the municipality that – due to pressure from civil society – tried to withdraw the financial aid for its construction ultimately had to pay compensation to the facility’s owner.

This example shows that people link their activities to their local community and that some forms of political participation are more acceptable and feasible than others. The protest for the relocation of the cattle barn is a rather exceptional case, as it is elite-challenging in its nature. One of my research participants illustrated the otherwise cooperative mode of participation dominant in the region: “When I think, that something good should be done, I’ll do it with my friends (nakama). Then, little by little, the scope will increase. We are not doing an opposition movement (hantai undō), that’s not what I imagine [as shimin undō]”.

Political participation in rural Aso takes place in the context of local decision-making processes that are linked to dominant perceptions of what “Aso” should be like. Oppositional movements are rare and are not viewed as an option of political participation by many of my respondents. Nevertheless, the municipalities are vibrant and show numerous small changes often taking place in the informal everyday lives of the local community. Subjective goals and ideas have to be carefully adjusted to the dominant power structures in rural Japan, sometimes making expressive activities hard to perform, as the example of the movement for the relocation of the cattle barn suggests.

Sebastian Polak-Rottmann is a PhD candidate at the Department of East Asian Studies at the University of Vienna. He is part of an interdisciplinary research project funded by the Austrian Academy of Sciences on subjective well-being and social capital in rural Japan. For his dissertation, he conducted semi-structured interviews in the Aso region to understand the relationship of political participation and subjective well-being.

References

[1]

Gotō, Tazuko. 2017. ‘Gyūsha kensetsuchi ‚iten o‘, Aso-shi ni jūmin ga seigansho, shomeibo, kankeisha no taiō kamiawazu, Kumamoto-ken’. In Asahi Shinbun, 16.12.2017: 28.

by Chris McMorran

In January 2022 I was finally able to visit Japan after a two-year gap. Two years of lockdowns, canceled research trips, and courses, meetings, and conferences moved online. Covid-19 disrupted my annual cycle of taking students to Kumamoto each May, visiting Tokyo for short holidays, and visiting family in Kumamoto each New Year’s. My return in January 2022 coincided with 10 months of sabbatical away from NUS and Japan’s reluctant opening to non-Japanese visitors. I could only enter because of my Japanese partner. Japan’s tight regulations on foreign visitors had been polling strongly and boosting PM Kishida’s government, so I expected to find a “closed country” mentality on the streets of Tokyo and Kumamoto, where I split three months.

Instead, I found people as polite and welcoming as ever. Kids playing in the street in my in-laws’ neighbourhood said hello. Staff in shops and restaurants welcomed us enthusiastically. But I did not yet feel comfortable doing interviews or even visiting my usual fieldwork sites, around Kurokawa Onsen (Kumamoto). I feared introducing the coronavirus to the spaces and people I care about so much. I owed a massive debt to those people and did not want to jeopardize my future with them. So I spent my time researching spaces and ideas on the periphery of my main focus: the intersection of tourism and work in rural Japan. And I took advantage of our new shared technological abilities, sharing my latest work in online lectures.

During my three months in Japan I gave lectures for audiences at International Christian University (Tokyo), Kanazawa University and the German Institute for Japanese Studies (DIJ). Under the heightened restrictions from the Omicron wave of January and February 2022, all three talks were moved online. While I felt some disappointment, I was also uplifted by the fact that the online talks could be attended by a truly global audience. My lecture on ryokan for International Christian University could be attended by ICU professors and students, as well as ICU alumni (including one who currently works in a ryokan!), and some of my own students in Singapore. My lecture for Kanazawa University could be attended by super-busy ryokan owners from distant Kurokawa Onsen, and my lecture for the German Institute for Japanese Studies could be attended by researchers based in Europe. These lectures reminded me how broad the global interest is in rural Japan, as well as how inclusive and supportive the network of scholars is.

While in Tokyo, I was excited to encounter instances of rural Japan reimagined as a new space of combined tourism and work, in the form of the “workation” (work+vacation) Posters in trains and train platforms showed happy individuals sitting in the great outdoors, their laptops strategically open before them. Covid-19 reminded everyone of the inherent risks associated with congested urban spaces. Rural areas have provided a way to escape such risks—and even enjoy one’s work—by working remotely (“telework”). The rural workation moves beyond working from home, which carries its own risks of burnout. Rural Japan—accessible by train—promises the ideal solution. Seeing so many reminders of this reimagination of rural Japan was enough to spur a new research project, one that would have been unlikely had I not returned to Japan.

I also visited one of Japan’s oldest onsen, Dōgo Onsen in Ehime, to see how it was weathering the Covid-19 storm. Shopping streets that in normal times would be brimming with shops selling local delicacies and flooded with tourists sat half empty. Some shops were temporarily shuttered. In the shops that were open, staff waited eagerly for the next customer to arrive. The lack of guests meant we could easily bathe in Dōgo’s most famous public baths, without waiting in lines that can normally last hours. It was a reminder that Japan’s tourism industry has a long road to recovery from the coronavirus disruption. My time in Japan was over too quickly, but I was grateful I could reconnect with the country and be stimulated by new potential research avenues.

Chris McMorran is Associate Professor of Japanese Studies at the National University of Singapore. He is a cultural geographer of contemporary Japan who researches the geographies of home across scale, from the body to the nation. His is the author of Ryokan: Mobilizing Hospitality in Rural Japan (2022, University of Hawai’i Press), an intimate study of a Japanese inn, based on twelve months spent scrubbing baths, washing dishes, and making guests feel at home at a hot springs resort. He also co-produces (with NUS students) “Home on the Dot,” a podcast that explores the meaning of home on the little red dot of Singapore.

by Sarah Bijlsma

This week, Japan celebrated the 50-year anniversary of Okinawa’s return to the mainland. After being governed by the US since the end of WWII, the administration of the prefecture was handed back to prime minister Eisaku Satō (1901-1975) on the 15th of May 1972. On the anniversary day, the central and national governments held ceremonies simultaneously in Tokyo and Okinawa including a video message from the Japanese Emperor and Empress. In the months before the anniversary, national and local media platforms took the opportunity to publish articles, interviews, and visual content that address various aspects of Okinawa Prefecture. In this blogpost, I will discuss two examples that illustrate the different ways the Japanese media represents the prefecture.

One strand of publications echoes hegemonic discourses of ‘Okinawa difference,’ including romanticized representations of the islands’ distinct culture and social life [1]. NHK, for example, since April broadcasts the morning drama Chimudondon. The asadora tells the story of a farmer’s daughter from the lush Yanbaru area, who opens an Okinawan restaurant in Tokyo in her adult life. The scenes are full of natural sceneries, local dishes, traditional crafts, and the large families Okinawa is known for. In the third episode, when the girl is still a child, she talks with the father of a friend who just moved from the capital to her small village. Standing under a shikuwasa tree with the blue sea shines bright in the background, she wonders out loud, “Isn’t Tokyo a much more interesting place?” The man replies: “You know, to you this village is your hometown.” “My hometown?” the girl looks confused [2]. The natural environment, genuine human relationships, and use of the Japanese term furusato for hometown instantly evokes a nostalgic feeling for all that is lost in urbanized Japan.

What is noticeable, however, is that in addition to such romanticized representations media channels gave much attention to the ongoing social and economic issues the prefecture is facing—a different translation of ‘Okinawa difference.’ Especially regarding the US military presence on the islands and the relocation of the Futenma base to Henoko, news platforms do not shy away of featuring critical voices. Asahi Shinbun, for example, featured an interview with a woman who joined the protest march that was held in the streets of Naha on 15 May 1972. She recalls that on the day of the reversion, rain came pouring from the sky. It was not a celebrative atmosphere; while she was only a high school student, she was somehow aware that it was not the return that she had wanted. Yet only years later, when she started working with children herself, she became to understand the irrationality of the situation in Okinawa more deeply. Even after the reversion to Japan, sexual assaults of children and women by US soldiers and helicopter accidents continued to occur significantly. The woman states that she feels that Okinawans are treated as if their lives do not matter much. Land reclamation in the Henoko sea continues, while she does not believe that there is anyone in the prefecture who agrees with that [3].

During the ceremonies on the 15th of May, many references were made to Okinawa’s present-day issues as well. Prime Minister Fumio Kishida acknowledged Okinawa’s lacking economy and continuing burden of the bases, pledging to “steadily make visible progress on the alleviation of the burden while maintaining the deterrence offered by the Japan-U.S. alliance” [4]. Okinawa governor Denny Tamaki urged the central government to turn Okinawa finally into “islands of peace” [5]. These statements and the media coverage illustrate that there is an increasing ground to openly debate social issues in present-day Japan. People more often take a clear stance; a newly conducted survey by Kyodo News showed that ca. 80% of the Japanese does not find it fair compared to other prefectures that Okinawa hosts more than 70% of Japan’s US military bases [6]. It is my hope that these and other debates continue to be held in and outside of Okinawa, also after this ‘anniversary’ year.

References

[1] See for example Hein, Ina. 2010. “Constructing difference in Japan: Literary counter-images of the Okinawa boom”, Contemporary Japan 22, 179-204.

[2] Chimudondon. NHK, 2022. Episode 3.

[3] Asahi Shimbun. 11 May 2022. (fukki 50 nen, sorezore no Okinawa) demo shashin ni, kōkōsei datta watashi kyōin ni nari rikai shita, Okinawa ga seou rifujin [(50 years after return, every Okinawa) I was a high school student on the photo of the demonstration, when I became a teacher I understood the irrationality that burdens Okinawa].

[4] Kyodo News. 15 May 2022. “Okinawa marks 50 years since reversion to Japan.” Via: https://english.kyodonews.net/news/2022/05/48ab72b43dd5-okinawa-marks-50-years-since-reversion-from-us-rule-as-bases-remain.html

[5] Kyodo News. 15 May 2022. “Okinawa marks 50 years since reversion to Japan.” Via: https://english.kyodonews.net/news/2022/05/48ab72b43dd5-okinawa-marks-50-years-since-reversion-from-us-rule-as-bases-remain.html

[6] Japan Times. 5 May 2022. “Nearly 80% of Japanese think Okinawa’s base-hosting unfair”.