by Asina Kara

At the end of 2018, I did an international youth volunteer service in a retirement home in Hiroshima City for one year and was fascinated by the area. The city center itself is not as big as in other Japanese cities such as Kyoto, Osaka or Tokyo, but it offered everything I needed. I lived on the outskirts of the city. I come from Berlin, so it felt very much like country life. But I felt connected to nature for the first time in my life, which went hand in hand with a sense of freedom. Since I have so many fond memories of Hiroshima, I would want to live there again. As in my case, where you move can be by chance. But often, people move to places they already have a connection with. This is true for two Japanese families who decided to move to a small town in Hiroshima Prefecture away from the crowded city and towards more freedom. But how much freedom do families have when they bring their children? In this post, I will introduce the experience of two families who moved to the countryside.

Hiroshima Prefectures is famous for its beautiful landscape and heritage sites like the torii of Itsukushima Shrine

Copyright © Asina Kara 2018

Takanori and Mikasa moved from Tokyo to a small town in the northeast of Hiroshima Prefecture in 2021 because city life became too stressful for them and they wanted to take over Mikasa’s grandparents’ house. They had the house renovated and live there with their two young daughters. Digital transformation allows them to do many things digitally “thanks” to the Corona pandemic. Takanori is employed in Tokyo but now works remotely. This is very compatible with his family life, as he can now spend more time with them. Mikasa, meanwhile, works in their field. They love having food, work and their children in one place and often eat home-grown vegetables, rice and meat from wild boar and deer that Takanori has hunted himself. The older daughter, however, feels lonely at times because she left her friends behind in Tokyo, but also enjoys spending time with her new friends, even though her class consists of only eight students. The younger daughter, on the other hand, likes to collect horsetails and chestnuts by the wayside, which makes family walks much longer. The family really enjoys spending time together in nature. Mikasa believes that her children can gain experiences in the countryside that would not be possible in Tokyo [1].

Small towns and villages in Hiroshima Prefecture attract many young urbanites.

Copyright © Asina Kara 2018

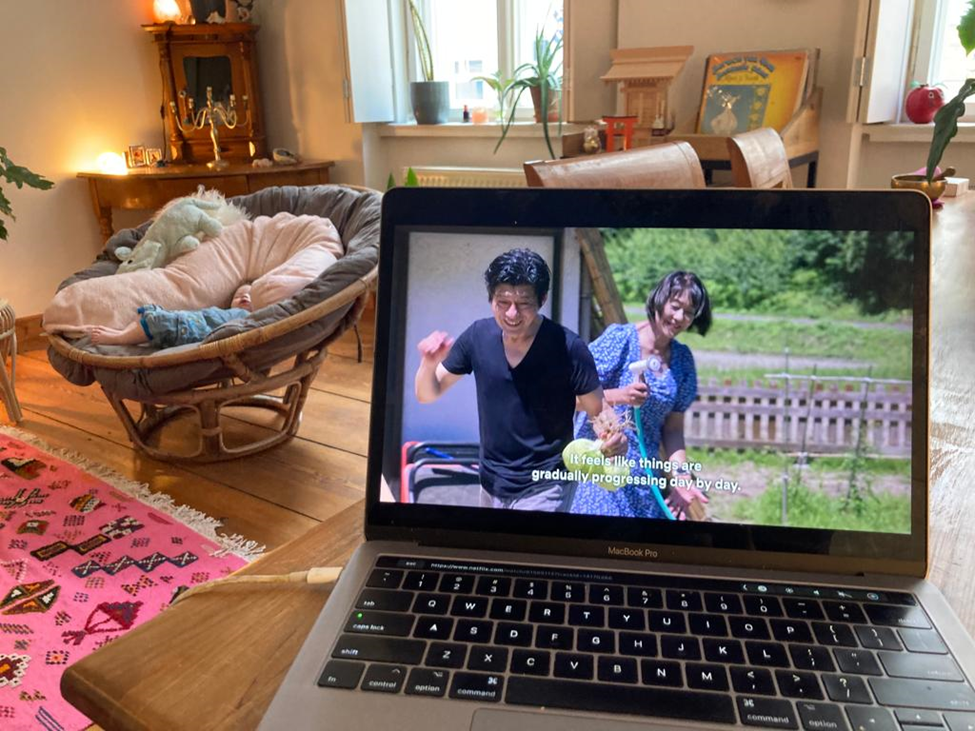

Jinsaku was born in Hiroshima City and moved from Tochigi Prefecture to a small town in the southeast of Hiroshima Prefecture. In Tochigi, he had worked for a large machine manufacturer and then quit because he began to doubt his life as an employee as he was constantly under time pressure. He became a farmer and has to work hard every day. He became interested in the small town where he now lives when he saw a 150-year-old house there. He rebuilt it and now earns a living there. His dream was to have a happy home with a family, which came true when he married and had two daughters. With his wife Chiaki, he initially grew and sold vegetables, but this was not enough to support the family, so they decided to focus on viticulture. This helped to support the family financially. Together with the children, they eat some home-grown vegetables, but now spend most of their time growing grapes [2].

Many urban-rural migrants start farming after moving to Hiroshima Prefecture

Copyright © Asina Kara 2018

These two examples show that work-life balance seems to be quite possible, but both families sacrifice a lot of time to farming, and one family struggled to maintain a stable income. Takanori had the opportunity to continue his old job remotely from Tokyo. So he has a stable income and is also financially independent from farming. This means that the family could make a living even if Mikasa did not earn so much money from farming. This gives the family security. Jinsaku, on the other hand, has become dependent on farming and therefore has to sacrifice more time. The pressure to feed his family is correspondingly higher. So in terms of livelihood and income, the experiences of these two families are very different. But whether part-time farming or full-time farming, both are physically demanding and should not be underestimated. However, rural life for a family does of course have its nice sides, because the children can move freely outdoors, they can eat the harvested vegetables together with the family and the family can spend time together in nature, which would be difficult to do in a big city.

References:

[1] Hiroshima-ken (2022), Tanbo to hata o te ni shite yume datta shizen nō o jitsugen, https://www.hiroshima-hirobiro.jp/interview/details/002055/, last accessed 27 June 2023.

[2] Hiroshima nyūsu (2020), Ijū kara 13-nen datsusara nōgyō seinen no “yume no tsuzuki“, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NhBxEBk_2IM, last accessed 27 June 2023.

Asina Kara is a student in the BA program in Japanese Studies at Freie Universität Berlin.