by Cornelia Reiher

Abandoned houses are one of the many problems rural areas in Japan are facing today. The so-called akiya mondai (abandoned house problem) also affects many urban-rural migrants (ijūsha). On the one hand, there are many abandoned houses; on the other hand, ijūsha often have difficulty finding housing because residents are unwilling to rent or sell their property, even if they no longer live there. The reasons for this are manifold and have been covered in other blog posts here. In one hamlet I visited, there were more abandoned houses than houses where people still lived. The population has dropped from 8000 to 800 in the last two decades. The local elementary school is on the verge of closing, and it is becoming increasingly difficult to find enough people to take care of community tasks like cutting the grass (kusakari).

Many abandoned houses in Japan decay and collapse because no one lives in them

Copyright © Cornelia Reiher 2022

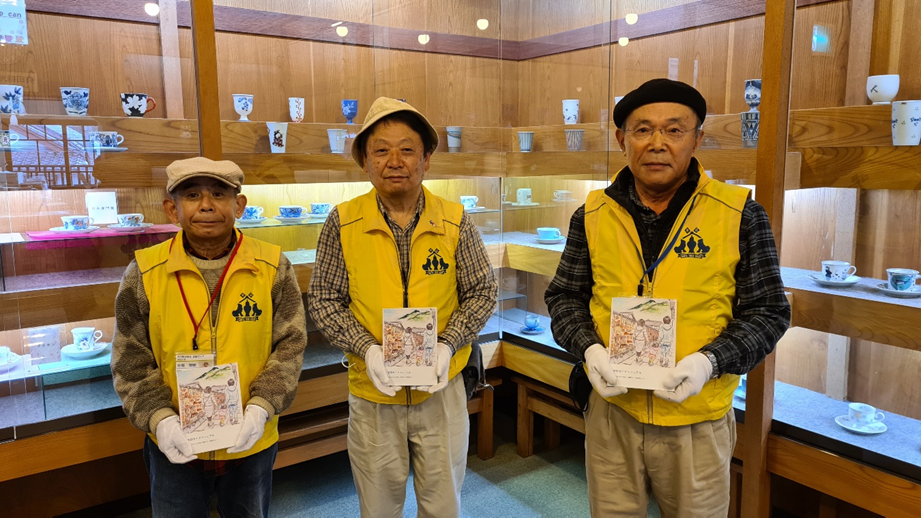

However, a couple, both ijūsha, recently settled in this hamlet and renovated two abandoned houses. One house has been converted into a gallery and café, the other is their home. Together with Kazuko (pseudonym), who runs the gallery with her husband, I visited the place several times during my field research in September and October 2022. It is located in a beautiful valley with rice paddies and small forests and offers a magnificent view of the nearby mountains. It can be reached from the city center in twenty minutes by car. In the hamlet itself there is a post office, a shrine, the elementary school and residential houses, many of which are empty. You wouldn’t expect to find a gallery here and would probably just drive past it, as there are no large signs pointing to it. However, at a second glance, one discovers some artwork inside and outside the gallery, including a mosaic created by an artist from Kyoto during a workshop.

A gallery in a renovated former akiya

Copyright © Cornelia Reiher 2022

When I visited for the first time, Kazuko’s husband, who is an artist himself, was busy preparing one of his own art works. In the exhibition room, preparations were still underway for the next exhibition. A sculptor was going to exhibit his work, and some of the pieces had already been unpacked. Kazuko and her husband showed me around and told me about the renovation work. The couple received no financial support. Since they did most of the work themselves, the renovation took several years. They tried to reuse as much material as possible that was already in the house. For example, since the previous owners had left most of their possessions behind, they were able to use some of the dishes for the café. They also reused much of the glass for the new windows and received a lot of help from artist friends who designed the stained-glass windows or the dishes Kazuko now uses in the café. A special feature of the house is the basement with its stone wall, which is now used as an exhibition space in addition to the ground floor. From the basement, you can look up at the exposed ceiling beams. In this interesting light, the sculptures looked quite mysterious.

A sculpture in the exhibition space in the basement and a table in the café with cookies and coffee

Copyright © Cornelia Reiher 2022

When I returned to the gallery a few days later for the exhibition opening with a friend, there were a few guests and the artists. After looking at the artworks on display, including many that had not been unpacked during my earlier visit, we ordered cookies and tea and enjoyed the beautiful view of the sunset, rice fields, and mountains. When Kazuko joined us, we chatted about the potential of art to revitalize rural areas. She believes that art can connect locals and newcomers, and stresses the importance of art, especially for children. That’s why she also offers workshops with artists for children and adults to create pottery or other artwork together. In addition to the on-site gallery and workshops, she also promotes local artists and artisans online, hoping to attract more people to the area. For now, however, most of the gallery’s visitors are friends from out of town and other urban-rural migrants.

Sunset view from the gallery’s coffee shop

Copyright © Cornelia Reiher 2022

This gallery is one of many examples of attempts to revitalize rural areas by promoting arts and crafts. Many rural areas have artist-in-residence programs, galleries, workshops and studios. They aim to preserve local craft traditions by inviting artisans or artists from abroad, or to promote their towns as attractive places for artists to work by offering low-cost or free studios, scholarships for artists, and exhibition spaces. However, many examples I came across were initiated by local governments, while the gallery described above is a purely private initiative. Although the owners have had to cover all costs themselves, it also means that they do not have to rely on subsidies that may one day run out, as is the fate of so many of these ambitious projects. I am curious to see how it will develop and look forward to visiting this gallery in the middle of nowhere again.