by Edzard Haschka

Although I have never set foot in Fukushima Prefecture myself, it, or rather the events that brought the region tragic global attention in 2011, is closely linked to my personal life story. From 2009 to 2011, I had the great opportunity to study at Takushoku University in Tokyo. Actually, I planned to study in Tokyo until I graduated in 2014, and who knows, maybe I would have stayed in Japan forever after that. When the earth began to shake at 2:46 p.m. on the afternoon of March 03, 2011, I was in the library of Takushoku University’s Bunkyo campus. At first, the ground began to vibrate slowly, as I had experienced from countless earthquakes, but after a few seconds, the shaking became stronger until I was the first person present to stand up and slowly walk toward the exit. The librarian noticed my worried look and said as the intensity of the shaking increased, “Maybe everything will be okay.” I quickened my pace and replied, “Maybe not.”

Takushoku University Bunkyo Campus, next to the Entry to the Library, Tokyo

Copyright © Edzard Haschka 2009

At that moment, about 15 seconds after the onset of the first tremors, Japan was shaken by the strongest earthquake since records began. As I ran outside, I saw some bookshelves collapse, cracks appear in the concrete of the floor and in the facade of the university, and the glass panes of the buildings caused a deafening clang. Shocked, we watched on a television screen an hour or two later as whole swaths of land not even 100 km from us were destroyed by the strongest tsunami mankind has ever seen. But it was the disaster at the Fukushima nuclear power plant that triggered the consternation in me, and especially in my family, that made it necessary to abandon my enthusiastically pursued plan to stay in Japan and start the journey home – a decision I still don’t regret today.

So much for my personal Japan story, which ended on March 14, when I left Japan as a “flyjin”. Back in Germany, however, the catastrophe never left me. I followed with concern about the attempts to contain the nuclear catastrophe and the helplessness with which mankind faces the threat of radioactive contamination. This invisible threat, against which people can protect themselves only at an extremely high cost and only for a short time, led to the establishment of exclusion zones in the region around Fukushima, a measure that left thousands of people homeless.

View towards Korakuen from the rooftop terrace of Takushoku University’s main building on the Bunkyo campus, Tokyo

Copyright © Edzard Haschka 2011

Given these circumstances, it is noteworthy that the efforts of Japanese institutions to revitalize regions in Japan that are threatened with depopulation also extend to the Fukushima region. In my research on efforts to revitalize remote regions, I came across a very interesting website run by Fukushima Prefecture. The website, https://fukushima-ijyu.com/, is the official website for those seeking assistance in resettling in Fukushima Prefecture. The website explicitly promotes resettlement to the region based on specific exemplary migration stories and interviews. The website features (as of June 26, 2023) interviews with 30 ijūsha (internal migrants) who have moved to the Fukushima region for various reasons. Some of them are from Fukushima and lived temporarily in one of the major Japanese cities, while others are from other areas of the Japanese archipelago. The selection of ijūsha gives the impression of a representative cross-section of the population, as both men and women, single people and parents of families from different regions are presented. As different as the circumstances and reasons for migrating to the Fukushima region may be, what all migrants have in common is that the decision to migrate was made out of an inner drive and was voluntary and positively inclined.

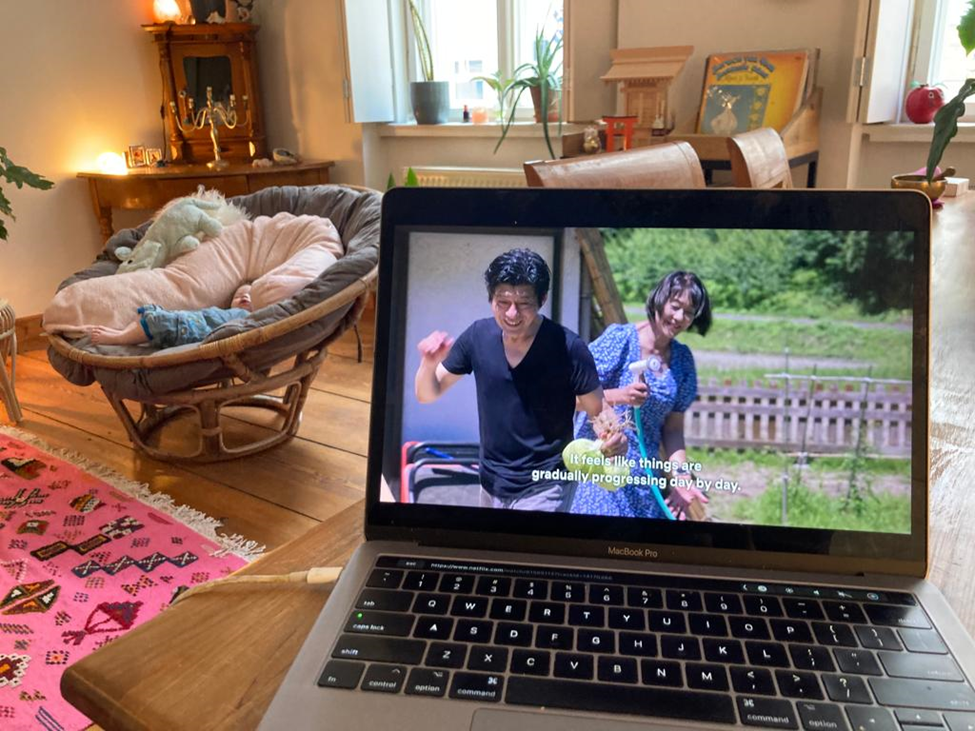

Through images similar to this one, the Fukushima Prefecture administration describes the site as an uncontaminated rural idyll, Fukushima Prefecture

Copyright © Rikako Matsuoka 2020

Services offered on the website include answers to frequently asked questions, contact forms to counseling centers, and referrals to support services. I was surprised, however, that the nuclear disaster and its impact on the region are not mentioned on the website, not even in an appeasing way. Even for unconcerned newcomers to the region, learning a few things about radiation might be significant. I also expected to find some information for refugees such as displaced people who need to resettle quickly. So I wondered how the post-disaster evacuation and the new attempts to attract migrants to Fukushima are connected. Who are the relevant target groups for promoting the region as a destination for migrants, and why would people consciously choose to migrate to the Fukushima region? In my opinion, this raises interesting research questions and challenges to be addressed with regard to migration to the Fukushima region.

References

Dambeck, Holger (February 28th, 2012): “Japans Regierung fürchtete Evakuierung Tokios”, Spiegel Online: /https://www.spiegel.de/wissenschaft/technik/fukushima-katastrophe-japans-regierung-fuerchtete-evakuierung-tokios-a-818084.html (last viewed on June 23rd, 2023).

Kan, Naoto, and Jeffrey S. Irish (2012). “My Nuclear Nightmare: Leading Japan through the Fukushima Disaster to a Nuclear-Free Future”. Cornell University Press.

Official website of Fukushima Prefecture for those interested in relocating to this prefecture: https://fukushima-ijyu.com/interview (last viewed on June 28th, 2023).

Edzard Haschka is a student in the BA program in Japanese Studies at Freie Universität Berlin