by Christoph Barann

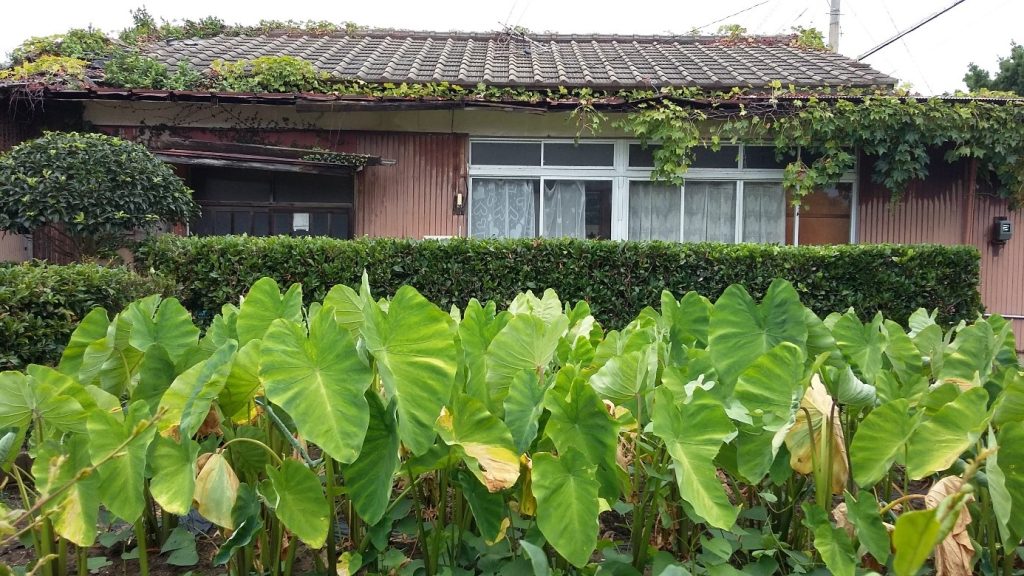

A traditional Japanese-style house (kominka) over 100 years old in the middle of a beautiful Japanese garden provides a home for the unconventional non-Japanese Andy. The American software engineer decided to move with his wife to the new house in a rural part of Wakayama Prefecture after previously working for large technology companies in Tokyo and the United States. Andy’s move as a technology-oriented foreign migrant to a rural town in Japan is emblematic of a change in the world of work in 21 century Japan. In our course on rural Japan, we have talked about many migrants similar to Andy. They are foreign, mostly young, highly skilled people who have not settled in the traditional work centers of Japan such as Tokyo, Osaka or Fukuoka. Instead, all these migrants have taken advantage of technological developments and changing working conditions in Japanese companies to enable a move to quiet, natural landscapes without jeopardizing their jobs (Wakayama Life n.d.). What all these migrants have in common is that they make use of remote working (terewāku), where internet technology is used to work from home for companies instead of commuting to the office. Remote working has taken root in Japan during the Covid-19 pandemic from 2020 as an alternative to traditional office jobs. The Covid-19 pandemic prompted Japanese companies to look to other regions such as Southeast Asia, Western Europe and the United States, where remote working was already an established method before the pandemic. Although the number of home workers declined as the pandemic subsided, the concept has nevertheless remained an important issue in the question of employment in modern Japan.

Copyright © Cornelia Reiher 2022

Andy’s interview on a website promoting migration to Wakayama Prefecture mentions a trend that is still common in Japan today. (Mostly male) workers leave their rural homes during the week to commute to jobs in the big cities. Often they do not return home at all during the week and live in second homes near their workplace. Remote working can offer a solution to the emotional and financial hardships that such a routine can bring by allowing people to work for companies in the big cities or even abroad without leaving their rural homes. Remote working may also lead to a change in Japanese attitudes towards employment and, in particular, hierarchies within Japanese office culture. Japan’s culture of long hours, overtime and strict hierarchies has been blamed in the past for the country’s demographic decline, as married couples struggle to balance work commitments with raising children. A less hierarchical office culture could also encourage the influx of highly skilled workers from abroad as Japan becomes a more attractive country to work in.

Copyright © Cornelia Reiher 2022

As part of a broader Digital Agenda for Japan, former Prime Minister Kishida sought to increase the availability of internet in rural areas and mentioned teleworking among other aspects aimed at improving Japan’s place among advanced economies in terms of digital standards. The digital strategy promotes teleworking, especially in small and medium-sized enterprises, and particularly emphasizes equal work opportunities for people in urban and rural areas. As access to reliable high-speed internet is expected to increase in rural areas and Japanese companies are increasingly encouraged to offer remote work to their employees, regions affected by depopulation and economic hardship could be given a chance to revitalize. Local governments, which have begun to encourage rural migration by offering free housing or other benefits to immigrants from urban areas, could in future offer courses in IT-related skills or provide free internet or shared office space geared towards remote working to turn their cities into “smart cities”, a concept that has already achieved some success in Southeast Asia. Remote work also appeals more strongly to a younger, more technically adapt generation and thus offers the possibility of creating migration of skilled workers in their 20s and 30s, a group which is heavily needed in the aging and depopulating rural regions of Japan. (McKinsey and Company 2021). Digitalization and remote work could therefore be a big aspect of the future revitalization efforts of Japan’s rural areas and might play an increasing role in the coming years.

References:

Wakayama Life (n. d.), “Mainichi miru keishiki ga kirei,” https://www.wakayamagurashi.jp/totteoki_life/03/ [access July 20, 2024]

McKinsey and Company (2021), Japan Digital Agenda 2030, https:/www.digitaljapan2030.com/ [access July 12, 2024]

Christoph Barann is a student in the BA program in Japanese Studies at the Freie Universität Berlin.