by Stephan Bogedain

The number of vacant houses in Japan has been increasing nationwide due to a declining population caused by low birth rates. These vacant houses are called akiya and have many negative effects on the living environment of the area and the population living in the neighborhood. They also have an impact on the local economy, as they lead to a decrease in land prices and tax revenues. Many of the vacant houses are not sold because Japanese people prefer not to buy used houses. In addition, many of them are also used as storage space, second homes, or are awaiting renovation (Platz 2024: 43-44).

The scenic cityscape in Kawagoe

Copyright © Diana Bondarenko (Unsplash) 2024

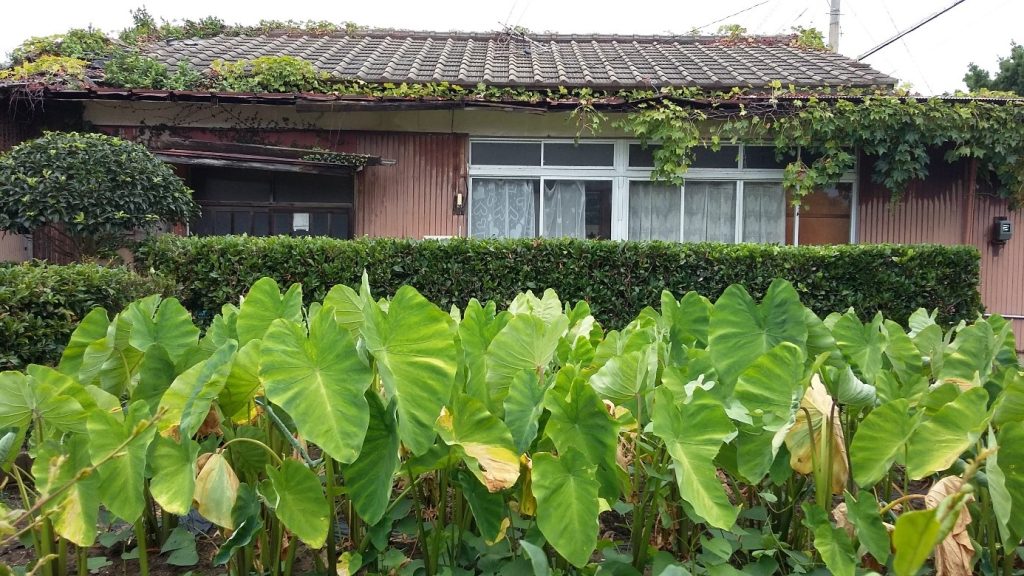

Located in Saitama Prefecture, Kawagoe is a city bustling with tourists who venture through the alleys to experience the traditional houses reminiscent of Japan’s Edo period. As many as seven million tourists visit Kawagoe each year to experience its unique and beautiful cityscape. However, the majority of these tourists only stay for the day and leave in the evening. The city has been experiencing steady population growth since the 1990s, but it is not free of the problems that akiya (City Population 2022) present. Due to the city’s massive success as a tourist attraction, rents are rising, and as a result, small private businesses are struggling to find a foothold in the area. This leads to these businesses being pushed out of Kawagoe and new ones being unable to open in the city, which negatively affects the residential areas (Seki 2022: 81). Since the main street sees a lot of visitors, it flourishes and is full of souvenir shops. The side streets, on the other hand, are deserted and the shopkeepers there are forced to give up their businesses.

Traditional houses in Kawagoe

Copyright © Diana Bondarenko (Unsplash) 2024

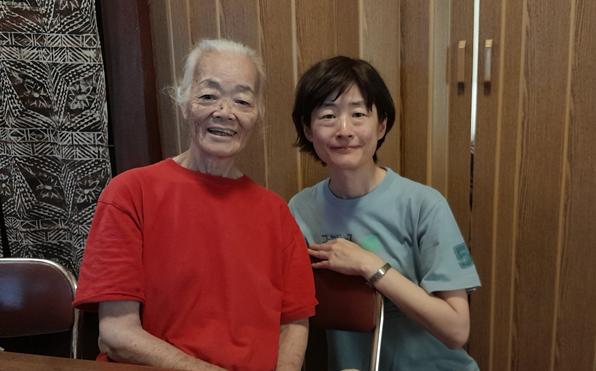

To address these issues, the city has formulated a plan to combat the increase in vacant properties. This includes raising awareness among citizens. The city also states that the owners of the houses are responsible for the proper management of the houses. However, the city will assist the owners if needed. The plan advocates the effective use of the empty spaces as community spaces in an attempt to revitalize the region. The focus of the revitalization is on areas with many elderly residents and vacant houses (Kawagoe City 2018a). According to a study carried out by the local government, the areas with the most vacant houses also have the highest proportion of elderly people over the age of 65 (Kawagoe City 2016: 75). While the city is generally experiencing population growth, it still faces the same problem of an increase in akiya due to an aging population. As part of the counter-measures, the city has started to collect data on vacant houses that their owners want to sell and is collecting them in a so-called vacant house bank (akiya banku). This makes it easy for individuals and organizations interested in buying a house to find and contact the owners (Kawagoe City 2023).

Some traditional houses in Kawagoe are being put to new use

Copyright © Diana Bondarenko (Unsplash) 2024

The city has also set up a school to teach how to renovate old vacant houses. Among the participants in this school is a group of people who have formed a company called “80%”. The company’s activities focus on repairing and renovating empty houses so that they can be reused for new businesses, such as coworking spaces and guesthouses, allowing 80% to make a profit by renting out the newly created spaces. The company renovates about one house per year. An example is the renovation of an old tenement that is now a rentable coworking space and café. The city’s 350,000 residents live alongside the many tourists who visit Kawagoe. The renovation projects serve as a way to make the city more livable by creating more businesses primarily for locals, which in turn can attract more tourists, while creating spaces where both worlds can meet and mix (Seki 2022). Their coworking spaces are advertised as having a cozy atmosphere and they offer their services 24 hours a day, 365 days a year (80 %). The company does not receive financial support from the local government for its projects, as it is a for-profit business. However, the city provides soft support to the group by arranging meetings and mediating between them and previous homeowners. Although the members of 80% are aware that they are doing a lot of work for the city, they also value having fun while renovating houses and want to make the city a place that reflects these values. Their sentiment is reflected in the name 80%, which means “creating a better day without working too hard” (Seki 2022: 83).

References:

80% (2024), “Kowākingu” [Coworking], https://80per.net/coworking/ (17.06.2024).

City Population (2022), ,,JAPAN: Saitama”, https://www.citypopulation.de/en/japan/saitama/ (17.06.2024).

Kawagoe City (2016), “Kawagoeshi akiya nado jittaichōsa hōkokusho” [Kawagoe vacant houses survey report], https://www.city.kawagoe.saitama.jp/kurashi/jutaku/akiyataisaku/jittaihoukokusyo.files/h28_jittaityousahoukokusyo.pdf (17.06.2024).

Kawagoe City (2018a), “Kawagoeshi akiya nado taisakukeikaku wo sakutei” [Formulated plan to deal with vacant houses in Kawagoe], https://www.city.kawagoe.saitama.jp/kurashi/jutaku/akiyataisaku/akiyakeikaku.html (17.06.2024).

Kawagoe City (2023), ,”Akiya banku” [Vacant house bank], https://www.city.kawagoe.saitama.jp/smph/kurashi/jutaku/akiyataisaku/bank-hp2.html (17.06.2024).

Platz, Annemone (2024), “From social issue to art site and beyond – reassessing rural akiya kominkan,” Contemporary Japan 36, 1: 41-56. 43-44.

Seki, Kōya (2022), “Kankōbaburu no ato no kawagoe o omou.” [Thinking of Kawagoe after the tourism bubble], in: TURNS, April (51): 78-83.

Stephan Bogedain is a student in the BA program in Japanese Studies at Freie Universität Berlin.