by Joy Hendry

In 2019, just before Japan closed to outside researchers for what must have seemed a cruelly long time to young scholars waiting to do their planned fieldwork, I was lucky enough to make a nostalgic visit to my own first fieldwork location. Thanks to the support of the Daiwa Anglo-Japanese Foundation, I donated some of the materials I had collected 43 years earlier, having decided they were better off in the village than gathering dust on my bookshelves. Moreover, my son and his partner were able to join me and make a documentary film about the visit, which I was delighted to discover could be enjoyed by many classes being taught remotely, also due to the pandemic.

land which used to provide fuel.

Copyright @Joy Hendry 2019

The older villagers remembered the year I had spent as a doctoral student, for there were few foreigners in rural Japan at the time, and my husband and I were a rare sight. Later I took my children to visit, so the man filming them had also been there as a youngster, and of course, the youth group of that time were now running village affairs. They were incredibly welcoming, as they had always been, and the family who had been next-door neighbours to my husband and I opened their home to us, as they had done on several previous visits over the years. There has been reciprocity, of course, and I have just introduced their great granddaughter to the Hall in Oxford used in films of Hogwarts School of Harry Potter fame.

Copyright @Joy Hendry 2019

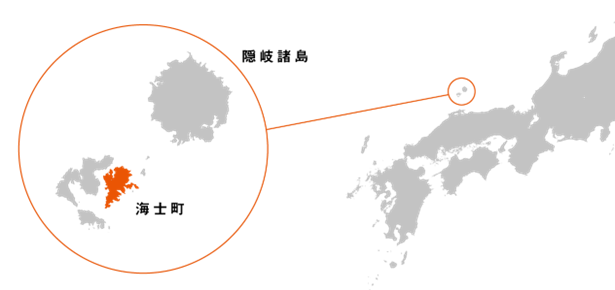

The village of 54 houses has shrunk slightly over the years, and a few newcomers have settled there, but the majority of residents are long-term, continuing families, though the younger generations have often found themselves homes separate from their elders. This is one of the changes since I first lived there, but there are still multiple generations working together on the growing of tea, first introduced as a pilot scheme a few years before I arrived, and chrysanthemums, which flourish in electrically lit greenhouses to allow them to flower for the New Year. These crops have largely replaced the papermaking which had been practiced in 30 houses in the past.

Other crafts I observed, such as bamboo work and lantern-making, have been replaced by businesses such as the supply of local stoneware, manufacture of vinyl bags, and a care home. One resident has a thriving carpentry business which is not new – he was trained in the community – and he was another visitor to Oxford, where he and his son built my university a small but charming Japanese room. His other son will carry on the trade, and between them these young men have added six children to the local school system, quite an achievement as Japan watches the birthrate plummet. A family which collected honey when I was first there has also grown the business and now exports it far and wide, again with generational continuity.

Another couple still thriving in the village invited all their grandchildren round to meet me on this visit. By chance their wedding had taken place during my first stay and their photograph appeared on the front of the book based on my doctoral research. Some of their relatives appeared on the cover of my second book so they laid both out for a family photograph along with albums of other events which have taken place over the years.

Copyright @Joy Hendry 2019

It has been a highlight of all my visits to Japan to return to this community, on one occasion with a BBC crew to make another educational film, always to find out how rural life was changing. Fewer people are to be found walking in the streets of the village – they drive out to their fields and greenhouses in their cars and farm vehicles, and there is no longer a village bath to bring everyone out of an evening. However, a splendid new village hall has been built, and it was used formally to receive the family trees and my diagram of how all the houses in the village were related, so there is clearly enough care and resource to give the community a good meeting place.

This visit was possibly my last, and during the pandemic I wrote a memoir of the experiences I have had there over the years, often wonderful, but sometimes frustrating, sad, and of course lonely. The book is called An Affair with a Village, for an anthropologist is always an outsider, marginal to “real life”. I started the book in 1976 so it was good to get it finished, and I hope it may inspire some of those setting out to start on such a career, even if their arrival was delayed, to build good relations with those who help them in Japan.

Joy Hendry is professor emerita of Oxford Brookes University where she taught the Anthropology of Japan for many years.