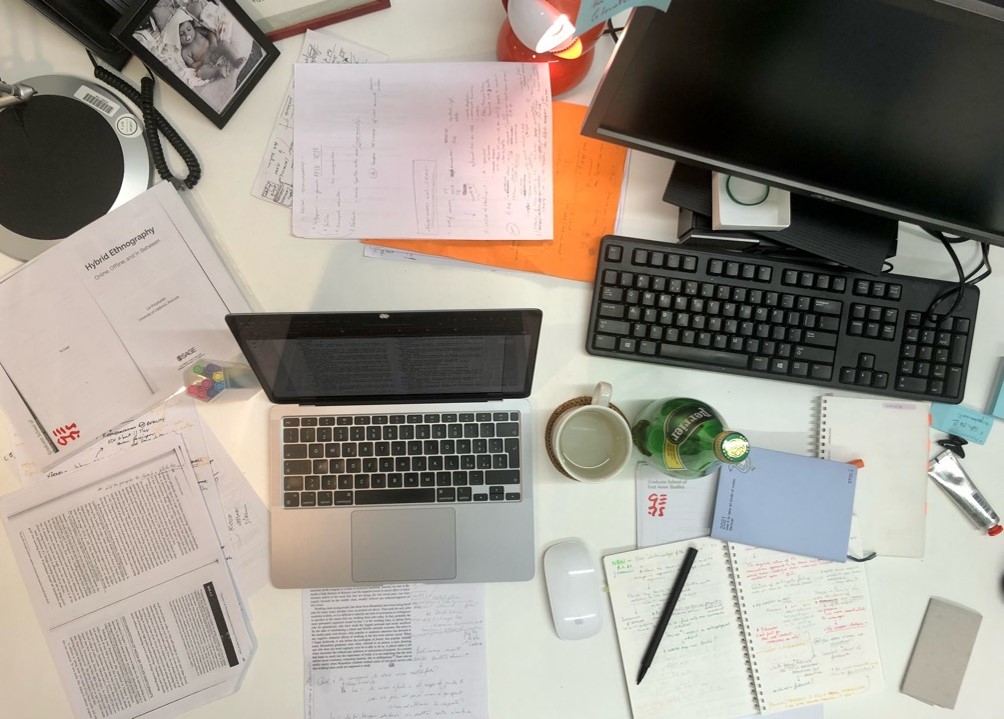

by Cornelia Reiher

Rural areas in Japan are connected with transnational networks in multiple ways. This transnational connectedness is not static, but can change over time as the example of Arita’s porcelain trade with Europe in the 17th and the 19th century shows. Transnational networks of the past can become an integral part of rural places’ history and identity and are often employed for the promotion of tourism and other revitalization strategies in the present [1]. In addition to these historical transnational connections, many non-Japanese citizens dwell in rural Japan. Some just stay there for a short period of time to study or work in Japan’s countryside, while others settle down, renovate abandoned houses, get married and raise children. Previous blog posts have already mentioned artists in residence from Europe, technical interns and members of the Chiiki okoshi kyoryokutai program from South- and Southeast Asia or Buddhist priests from England who reside in rural Japan. They all contribute to the revitalization of rural Japan in various ways and connect Japan’s rural towns and villages with other parts of the world.

Copyright © Cornelia Reiher 2019

But this is not the only way migration connects Japan’s rural areas transnationally. Many of the U-turn or I-turn migrants (and of course many of the long-term rural residents) have travelled and/or lived abroad before moving to the countryside. In her book on urban-rural migration, Susanne Klien [2] mentions that twenty of the 118 urban-rural migrants she worked with had lived abroad before. During my own research on urban-rural migration in Kyushu, I made a similar observation. One woman who now lives in Oita prefecture, for example, studied in Italy and fell in love with an Italian man. When their children were about to enter elementary school, the couple decided to relocate to Japan, because they wanted them to grow up in Japan. Although the Japanese wife is from a big city, they decided that they wanted to live closer to nature and relocated to a small town in the countryside where they now run an Italian restaurant, thereby contributing to the culinary diversity of the area.

Copyright © Cornelia Reiher 2018

Other urban-rural migrants are former members of overseas volunteer programs. These include programs initiated by the Japanese government like the Japan Overseas Cooperation Volunteers (JOCV) or by non-Japanese NGOs that provide assistance to developing countries via local projects. As of 2020, JOCV had dispatched 45,776 young Japanese between the ages of 20 and 39 to 98 countries for a period of two years [3]. Experiences abroad can contribute to greater awareness of social problems and inequality and to engagement for social change and a better world after volunteers’ return to Japan [4]. Based on this experience, some former volunteers want to contribute to the revitalization of Japan’s countryside. While participating in such volunteer programs in developing countries is evaluated as positive for the individual experience and growth of young Japanese adults and Japanese society, volunteers struggle with finding employment when they return to Japan [4,5]. This is one reason why many former volunteers move to the countryside and join another government sponsored program, the Chiiki okoshi kyōryokutai (COKT), that hires young adults who work in the countryside in Japan for three years and support local governments in activities aimed at rural revitalization [6].

Copyright © Cornelia Reiher 2019

These examples show how the mobility of people, their experiences and skills can impact Japan’s countryside, create and deepen transnational networks, inspire ideas and introduce new practices to the countryside. Instead of only focusing on urban-rural migrants and the migration from urban areas to rural areas within Japan, research on urban-rural migration should pay more attention to previous mobility experiences of urban-rural migrants to fully understand their impact on rural Japan and their migration trajectories.

References

[1]

Reiher, Cornelia (2014), Lokale Identität und ländliche Revitalisierung. Die japanische Keramikstadt Arita und die Grenzen der Globalisierung [Local Identity and Rural Revitalization. The Japanese Ceramic Town Arita and the Limits of Globalization], Bielefeld: transcript.

[2]

Klien, S. (2020), Urban Migrants in Rural Japan: Between Agency and Anomie in a Post-Growth Society, New York: SUNY Press.

[3]

JICA (Japan International Cooperation Agency) (2020), JICA Volunteer Program: Leading the World with Trust, https://www.jica.go.jp/english/publications/brochures/c8h0vm0000avs7w2-att/jica_volunteer_ en.pdf, last accessed October 30, 2021.

[4]

Iwai, Y. (2010), “Borantia taiken de gakusei wa nani o manabu no ka: Afurika to jibun o tsunageru sōzōryoku” [What Students Learn through Social Service Experiences: Awareness of the Connection Between Themselves and Africa], Hosei daigaku ningen kankyō gakkai [The Hosei Journal of Humanity and Environment] 10, pp. 1–11.

[5]

Kawachi, K. (2013), Constructing Notions of Development: An Analysis of the Experiences of Japan Overseas Cooperation Volunteers and the Peace Corps in Latin America and Their Interaction with Indigenous Communities in Ecuadorian Highlands, University of Texas [PhD dissertation].

[6]

Reiher, Cornelia (2020), “Embracing the periphery: Urbanites’ motivations to relocate to rural Japan”, in Manzenreiter, Wolfram, Lützeler, Ralph and Polak-Rottmann, Sebastian (Eds.), Japan’s new ruralities: Coping with decline in the periphery, London: Routledge, pp. 230–244.