by Cecilia Luzi

In rural Japan, life often revolves around exchange, reciprocity, and community support. These values profoundly influence the way people live and interact, especially among urban-rural migrants. This blog post explores how these values are manifested through a seemingly ordinary object-a used television found in the home of one of my research participants in Buzen. By examining the history of this TV, I uncover how such objects symbolize broader patterns of reciprocity and sustainability among urban-rural migrants.

Copyright © Cecilia Luzi 2022

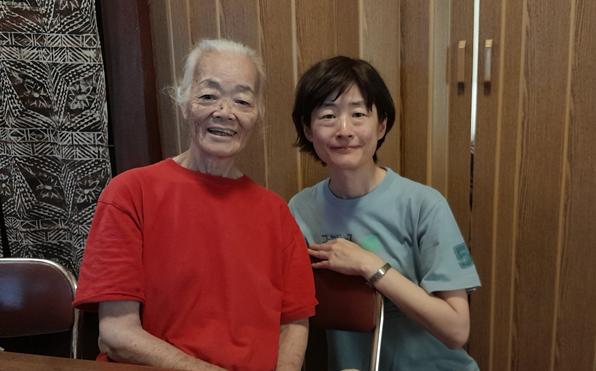

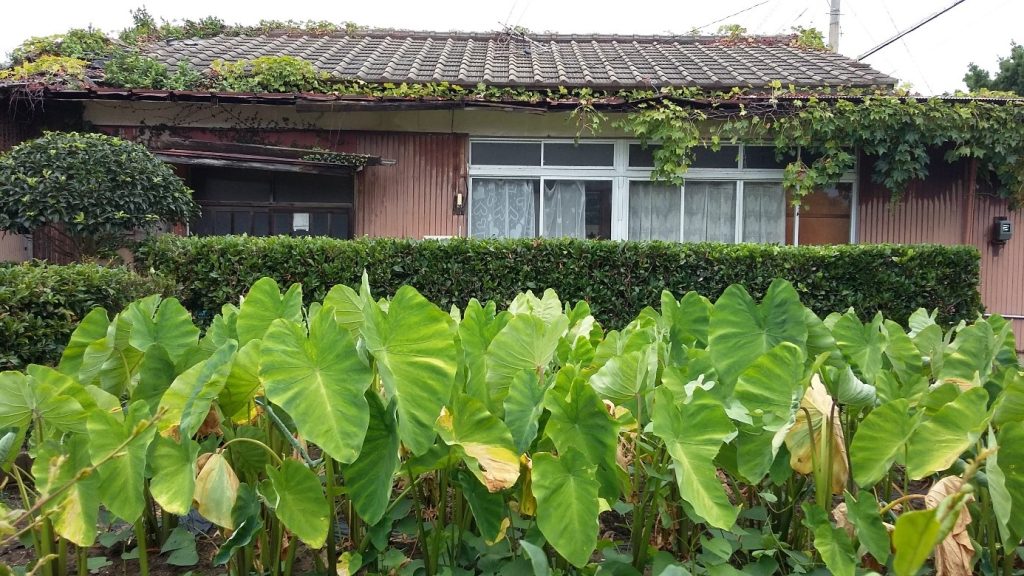

Hitomi, 43, originally from Kitakyūshū, moved to Buzen five years ago, shortly after the birth of her third daughter. After living in China, New Zealand, Singapore, the UK and Colombia, she now works as a translator, specializing in Chinese and English. Her family includes her Colombian husband and three daughters. She moved to live with her parents to help care for her grandmother, who suffered from dementia. This move also provided much needed support for her daughters while her husband remained in Colombia. Hitomi’s life is deeply rooted in the values of sharing and helping others, which is vividly illustrated by an object in her home. On my first visit to her home, I noticed a large, 60-inch flat-screen TV in the corner of the living area that doubles as the kitchen and family room. “That’s a big TV!” I said, and Hitomi replied, “Yeah, but it’s broken!” A friend had given her the TV when she moved into her rental house. “I still have to find the time and money to get it fixed,” Hitomi said. When I visited again a few months later, I saw that the room had been rearranged, with the TV now placed in front of the sofa. “Oh, so you finally fixed it!” I exclaimed. Hitomi laughed and said, “No, not yet. She explained that she didn’t want to throw it away because it was a gift from a friend and because “it’s a waste (mottainai); it could still be fixed!”

Copyright © Cecilia Luzi 2022

Exchange, reciprocity, mutual support and sharing are at the heart of Hitomi’s life. Hitomi connects effortlessly with people from all walks of life. Her life is a rich tapestry of relationships, and her genuine curiosity about others drives her to offer support and empathy whenever needed. I saw this in action when she helped a new JET participant from the UK find an apartment, shared details about a friend’s pastry class, and even took her daughter’s friend home from school for weeks at a time to help her mother, who had just given birth. “I’ve traveled and lived alone in many places,” Hitomi told me, “and if it weren’t for the help I received from so many people, I wouldn’t be where I am today. Helping you and others is my way of giving back some of that support to the universe.” In this context, the broken TV in Hitomi’s house has a special significance. It’s more than just a piece of furniture; it symbolizes her gratitude to the people in her life and reflects her commitment to a life rooted in interconnectedness and reciprocity. When Hitomi and her three daughters had just moved into their new home, the television was an unexpected and much appreciated gift. Given the expense of moving and settling into a new place, buying a TV wasn’t on her radar. It now sits prominently in her living room, a constant reminder of Hitomi’s social relationships built on sharing and mutual support.

Copyright © Cecilia Luzi 2022

During my visits, I noticed that Hitomi had moved the television from one place to another while she waited for it to be repaired. This in-between state, in which the TV no longer works but still has meaning, is a symbol of Hitomi’s commitment to a life centered on support, community, and sustainability, similar to many other migrants I met. The secondhand TV also underscores a more general trend that I observed among many people during my fieldwork. Urban migrants often rely on second-hand items, such as furniture and tools, and live a lifestyle focused on reuse and sustainability. This practice is also consistent with a deeper commitment to environmental awareness. Hitomi’s living room, a mix of old and new furniture, including the TV, sofa bed and dining table – all gifts from friends – exemplifies this trend. In this context, where secondhand items are both a necessity and a choice, these objects represent more than just sustainability. These objects, whether brought in from the city or purchased new, embody the relationships and exchanges between their former and new owners, forming a mosaic of objects and social relations, each with its own story.