by Cornelia Reiher

Two days after my arrival in Japan this September, Kyushu was hit by an “exceptionally strong typhoon”. This reminded me that the Covid pandemic was not the only reason that forced people to change their travel plans or daily lives. Typhoon No. 14 hit Kyushu on September 18, shortly after I arrived in Fukuoka, where I had planned to meet with our colleagues at Kyushu University before starting fieldwork in Arita and Taketa. Although I was safely ensconced in a high-rise concrete hotel, I was surprised to find that most stores, supermarkets, and even konbini in Fukuoka were closed. When I went to a supermarket that was still open, the shelves were quite empty, and I was lucky to buy the last obento.

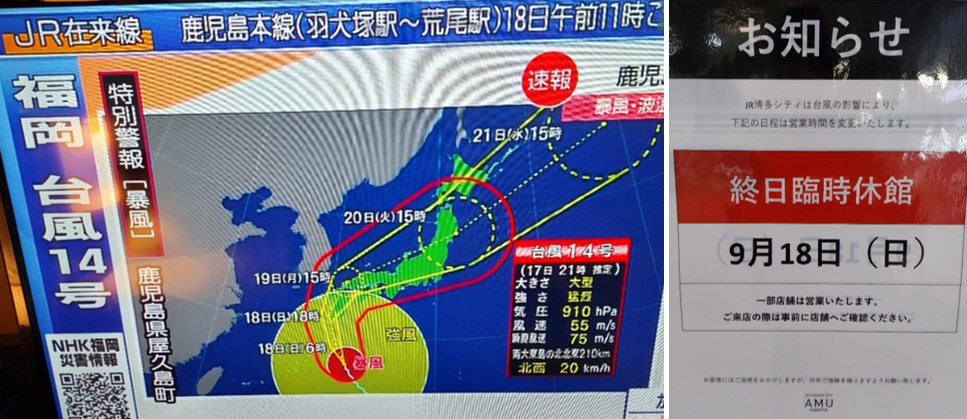

On television, news of store and train closures were updated every minute, and signs in the windows of Hakata Station informed customers of temporary store closures due to the typhoon.

Copyright © Cornelia Reiher 2022

Train, plane, subway and bus services in Fukuoka were also suspended, and people stranded at Hakata Station waited in long lines for information. Media coverage was quite alarming, and my emergency app recommended evacuating to a nearby gym, but hotel staff said the hotel was much safer. All people in Fukuoka were advised to stay indoors. While watching on TV as the typhoon hit the coast of Kagoshima with fierce winds, high waves, and a storm surge, I waited anxiously in my hotel room for the typhoon to hit Fukuoka. Finally, the typhoon had lost some speed as it passed Fukuoka early in the morning of September 19 while I was still asleep.

Homeowners put tape on their windows as a precaution against typhoons to prevent them from breaking.

Copyright © Cornelia Reiher 2022

The next morning, television showed images of heavy storms, flooded streets and fallen trees. A report from Yufuin showed that the roads were underwater. Many highways and businesses were still closed and train service was suspended. At breakfast, I overheard a waitress telling a guest that the entire hotel staff was sleeping in the hotel during the typhoon. I texted my friends in Oita and Saga and asked them if they were okay. Some had actually spent the night with their families in a shelter, but fortunately, no one had been injured. According to NHK, the total number of injured people in Fukuoka and Saga prefectures was very low, eleven and three, respectively. However, my friends and research participants were affected in different ways. Events they had been preparing for several months had to be canceled. One friend was stuck in Kokura for two days waiting for a connecting train. Others reported that the typhoon had broken windows or blown the roof off their homes. In particular, those living in renovated former akiya reported damage. Many experienced the typhoon as frightening and said this typhoon was much worse than previous ones, but others complained about the media spreading panic. Guesthouse operators told me that people were seeking refuge in the guesthouse.

In many places in Kyushu, the strong wind had knocked over the rice plants.

Copyright © Cornelia Reiher 2022

When I visited Saga and Oita after the typhoon, I could see some damage myself: In the rice fields, the typhoon had knocked over the rice plants just before the harvest. Therefore, the rice could only be harvested by hand. This cost the farmers more time and resources. In Oita, a large tree next to a local shrine was struck by lightning during the typhoon and large branches had fallen. Two weeks after the typhoon, local people were still busy cleaning up the damage. At the same time, they were also going about their usual activities, preparing for the annual Kagura performance at the shrine, which was being held for the first time in two years because of the Covid pandemic. This made me realize how resilient rural residents are to natural disasters. Instead of complaining, they cleaned up the damage and went on with their lives. Many even emphasized how lucky they were this time because, for example, the nearby river did not burst its banks. But natural disasters are always on their minds, which is reflected in damage prevention measures and visible in the rural landscape. For example, homeowners put tape on their windows to protect them from typhoons, but it is very difficult to remove. Therefore, it stays on for a while after the typhoon, and in some cases, it is not removed at all. Some people think of countermeasures when building or renovating a house and use the heavier roof tiles (kawarayane), for example, because the roof is more likely to hold up in a typhoon.

Branches of a tree struck by lightning during the typhoon.

Copyright © Cornelia Reiher 2022

In summary, this experience puts the pandemic in perspective as one of many risks and disasters that the rural population of Japan faces in their daily lives. I realized that I had focused too much on the Covid pandemic because I was unable to travel to Japan due to the pandemic. However, the spatial and temporal dimensions of these different disasters as well as the different social, economic, political and cultural impacts are perceived and handled very differently by people in the countryside. It is interesting to study how rural residents deal with these different risks and disasters and manage them in everyday life.