by Cecilia Luzi

In April 2022, my first year as a PhD student came to an end. Since maternity leave kept me away from my office for about seven months last year, my schedule changed, and I just entered what is supposed to be the “fieldwork year”. During the last months, I have been following migrants in Hasami and Buzen mainly through their social media profiles. Recently, I reached out to some of them, and I started to listen to their stories about the migration experience via Zoom. I will write more about this experience in the future, but in this post, I would like to follow up on Professor Reiher’s last article and reflect about doing research during a global pandemic.

right: My desk in dark winter afternoons Copyright © Cecilia Luzi 2021

When we started working in the project in October 2020, we did not realize yet that being able to be in Berlin at the same time, was already a great chance. Our offices face each other and being physically close encouraged the team spirit a lot. Moreover, when all classes for PhD students took place online, and most of other members of our cohort at GEAS were stuck in Japan, Korea or somewhere else in Europe, being here on campus helped us not to lose track of our own PhD projects. By simply being able to say hello in the morning across the corridor or have a chat while making coffee in the kitchen has been very helpful during these months.

Together, we developed ideas about how to continue our research during the pandemic. We went through a process of adapting our respective research together. Very often, we discussed how to overcome bureaucratic obstacles or just encouraged each other. Together we managed to remain positive even during confusing times. For instance, when the Japanese government closed borders again in the aftermath of the emergence of the Omicron variant in late 2021, the “Urban-rural migration and rural revitalization in Japan” research group was my source of strength even when working from home. I can never thank them enough.

right: Another office in a library in Italy in January 2022 Copyright © Cecilia Luzi 2022

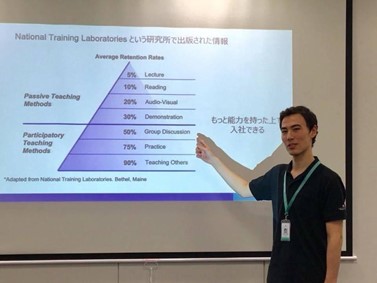

Yet, this was not our only support group. While learning how the digital space could be used to access the research field from our desks, we also started to use digital meeting tools to reach out other students and researchers with similar interests. In a short time, we set up an online study group meeting once a month. After a year and many meetings, I can confidently say that these meeting were incredibly useful for developing a research network, receiving feedback and discovering new research paths. The atmosphere in the study group is very cooperative and informal and I really enjoyed these moments of exchange with people from outside the team. I am very grateful to all the participants who stayed with us during all these months, and I really hope we will be able to meet in person one day soon.

Last but not the least, this blog was of course another door to the outside world and still keeps us connected with researchers on rural Japan and beyond. Contributions come from people with all sorts of backgrounds, different origins, and various interests, which makes the blog rich and vibrant. For me, writing in a blog is both a chance to reflect on the practice of dissemination of academic knowledge and an exercise of awareness for positionality. In fact, while putting my observations and thoughts out for a wider and more diversified public, I am forced to spend time reflecting about what parts of my research I want the blog’s audience to see and how I can convey them in less than 800 words. I experienced how a blog can “become a workspace for the ethnographer” (Beaulieu 2004, p.151).

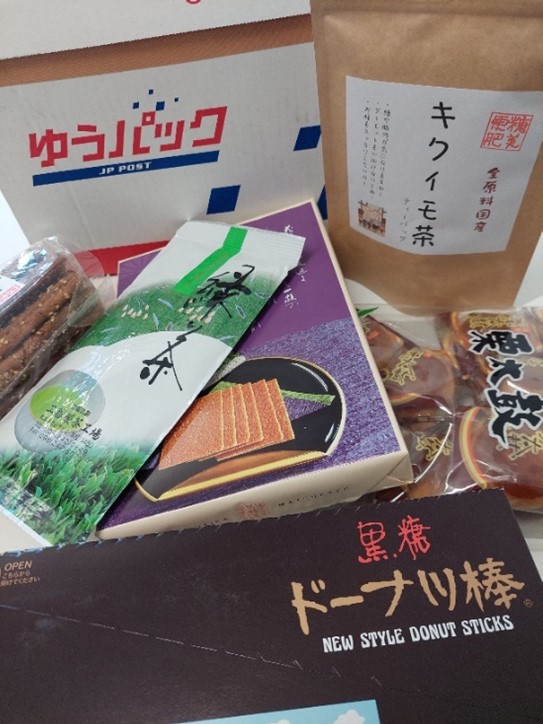

Copyright © Cornelia Reiher 2021

The fabric of social relations is what kept me afloat during these years of the pandemic. This is especially true when it comes to my PhD. Whether in the office wearing masks, or over Webex having Christmas parties, exchanging ideas and encouraging each other, within and outside our team, has always brought back the enthusiasm of the beginning. I value the relations built both in the “real” and “virtual” world. If there is one important lesson these hard times taught me, it is that social connections always can find a way through pandemic lockdowns, isolation and overcome any distance.

References

Beaulieu, A. 2004. Mediating ethnography: objectivity and the making of ethnographies of the internet, Social Epistemology, 18:2-3, 139-163,