by Susanne Klien

Fieldwork tends to be seen as a standard tool in ethnography, at least until the pandemic. Not so much has been written about exhaustions during and after fieldwork although some vivid depictions of challenges feature on this blog and are described in detail in Kottmann’s and Reiher’s Handbook of Research Design, Fieldwork and Methods (2020). Often, as researchers being indebted to a multiplicity of people in the field, we are less aware of the physical and mental tolls that the conduct of fieldwork in fact takes on our bodies and minds. Immersion constitutes immeasurable chances for us to gain new insights into the field. Yet, immersion also means pressure to miss out, as Harvey-Sanchez and Olsen (2019) observe: “Being forced to see how all the fragments are situated in a web of significance is draining at times. I feel like a vessel and an emotional labourer at once. Taking in all of the different fragments and being forced to see how they fit into a system of meaning, while also being attuned to every pause, every silence, every conversation, and the broader rhythm of speech and movement. I want to be able to unsee it, I explained at the time. Now I’ve learned how to turn on my ethnographer mode, but I need to learn how to turn it off. I want to take off the ethnographer hat –“

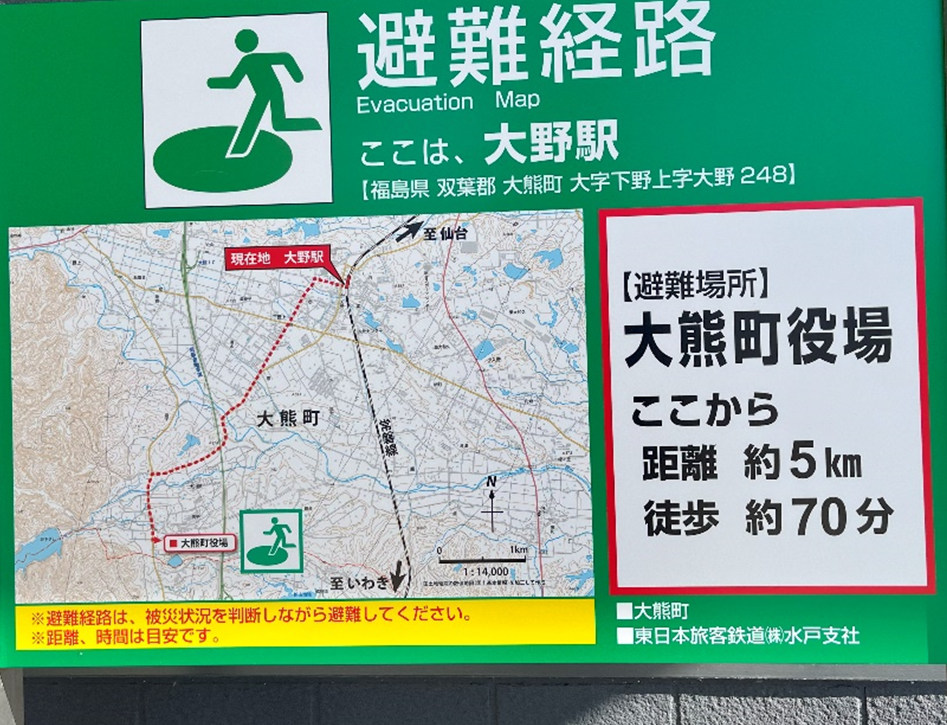

Life and death

Copyright © Susanne Klien 2021

From my own experience, it is often after returning home that the full impact shows: a sense of prolonged exhaustion that continues for one month or even more depending on the length and intensity of fieldwork. With increasing age and time constraints, the extent of exhaustion seems to grow. During my follow-up fieldwork of one month in Kamiyama Town, Tokushima in April-May 2021, the different climate, insect and concerns about how to conduct fieldwork during a pandemic were just some elements that seemed to enforce my sense of exhaustion. I remember dropping into the local public bath (onsen) every other day as a means of coping with my lingering physical tiredness. Soaking in the hot water worked wonders. I had been to the small rural town six years before, but still, finding a daily pace, re-establishing a network, accessing things, people, securing food – there were many potential sources of trouble, especially because this was at the height of the pandemic. This time, I stayed with an acquaintance who had set up a guesthouse in a small mountain village – a decision that helped me to get invaluable insights into the tensions between newcomers and locals. The elevated location of my accommodation offered an impressive panorama view across the picturesque valley. It also meant, however, an exposure to a vast array of insects, most uncomfortably, poisonous centipedes and leeches. During my stay, other guests were also exposed and with every day of my stay, I felt the threat of an encounter, especially because I was sleeping on a futon on the tatami floor. I witnessed the fiancé of my host expertly catching a centipede with chopsticks, an impressive feat. Towards the end of my stay, I detected one more of my centipede fellows next to my mattress. I felt a sense of triumph when I managed to catch it (admittedly, not with chopsticks) – ironically, next to Didier Fassin’s Life: A Critical User’s Manual, which I never got around to reading during my stay.

The narrow, curvy road leading to the guesthouse

Copyright © Susanne Klien 2021

The lingering sense of tension, a stiff neck, unfamiliar humidity, the fear of driving on the narrow, winding roads are all moments of immersion. At the beginning of my stay, I was ambitious enough to think that I would cook for myself. After the second day, however, I gave in to the temptation of sharing meals with my hosts. These meals were particularly enjoyable given that there were new guests and visitors every other day and even if there weren’t, these were wonderful opportunities to ask questions about the town and its people. These meals also provided chances to support local shops: I loved going to the (only) local butcher on the main street to get some meat as it was incredibly tasty. My hosts would contribute (mostly self-grown) vegetables – a perfect combination. I also liked to buy a few bottles of local craft beer in town for my hosts, guests and myself.

Kamiyama beer, local meat and self-grown vegetables of my hosts for dinner

Copyright © Susanne Klien 2021

But let’s get back to the ethnographer’s hat and how to get rid of it for one’s own and for the sake of one’s body and mind. In retrospect, I approached my follow-up stay as an extended immersive practice, even when I was sleeping, as I expected centipedes. The only time-out in a way was soaking myself in the hot water, enjoying the moment, trying to think of nothing. There were other instances of going to public baths in rural areas during fieldwork that were more social, so the practice of going to onsen as such may be multi-faceted depending on the field, one’s stage of fieldwork and many other factors. In any case, with more experiences of fieldwork in vastly different contexts, I feel that it is crucial to make sure that one allows for such moments of taking off the ethnographer’s hat and – ideally more extended time off out of respect for one’s body and mind.

References

Harvey-Sanchez, Amanda and Annika Olsen (2019). “Ethnography as Obsession: On Immersion and Separation in Fieldwork and Writing”, Ethnography of the University 2018: Focus on Politics, https://ethnographylab.ca/2019/01/07/ethnography-as-obsession-on-immersion-and-separation-in-fieldwork-and-writing/ accessed on 25 April 2023.

Kottmann, Nora and Cornelia Reiher (eds.) (2020). Studying Japan: Handbook of Research Designs, Fieldwork and Methods, Baden Baden: Nomos.

*Susanne Klien is an associate professor at Hokkaido University. Her main research interests include the appropriation of local traditions, demographic decline and alternative forms of living and working in post-growth Japan. She is the author of Urban Migrants in Rural Japan: Between Agency and Anomie in a Post-Growth Society (State University of New York Press, 2020).